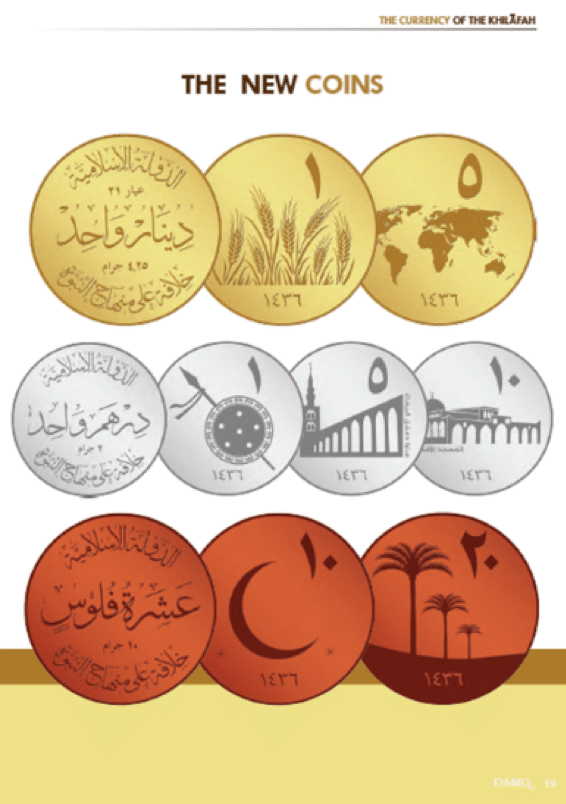

In November 2014, issue 5 of the Islamic State English-speaking magazine Dabiq (p. 19) unveiled a new currency to be soon minted and put into circulation: a series of seven coins divided between two gold dinars, three silver dirhams and two copper fulûs (sing. fils or fals).

Chapter I

In 2014, this monetary reform was part of a larger state building endeavour.

Although a theoretically ever-expanding Caliphate does not recognize international borders or traditional states, its leadership nonetheless strived to reproduce all the traditional signs of sovereignty: ministries for taxation and finance, health, justice and police, a legislative body and Shariatic tribunals. The Islamic State chose a flag – the black banner with the shahâda, selected what amounts to an anthem – a capella hymns called anashîd, ubiquitous in their propaganda videos, and, last but not least, they created a new currency. Minting of dinars and dirhams was the final component in solidifying the physical reality of the group’s millenarian utopia.

The new currency firstly served to self-reinforce legitimacy of the emerging jihadi state and realise the prophesised return of the Caliph. ISIS announced the revived Khilafah in Syria and Iraq by implementing monetary reform inspired by the Omayyad coinage reform, explicitly referring to the first series of Islamic coins[1] minted at the end of the 7th century.

This new ISIS currency was meant to replace the paper money of Syrian Pound, Iraqi Dinar and US dollar, the three most commonly used currencies in the area then controlled by the Islamic State.

Predictably, the group’s new financial policy was both brief and chaotic. However, it did serve what was one of its main purposes, adding a further layer of legitimacy and authenticity to the Caliphate-building endeavour. This was a rather revolutionary strategy within a Salafi-Jihadi ecosystem articulated on small insurgency groups and clandestine networks. The gold dinar and silver dirham came to gild the false ceiling of a utopian State already overloaded with kitsch paraphernalia[2] exalting the return of the King and cavalry charge, jihadi-warrior lyrics, baroque prophecies and apocalyptic battles.[3]

The coinage put into circulation were partially inspired by 7th century Omayyad models. They went through different stages of development but usually bore the profession of faith (shahâda) surrounded by references to the prophetic mission of Mohammad, an extract of the Qur’an, and the minting date. Borrowing characteristics from the first Islamic coins produced by Abd al-Malik Ibn Marwan’s (646-705) caliphate was an attempt to recapture some of the prestige of the first Arab dynasty that had made Damascus the heart of an Empire.

The rejection of banknotes signalled a decisive exit from the international financial system, “In an effort to disentangle the Ummah from the corrupt, interest-based global financial system, the Islamic State recently announced the minting of new currency based on the intrinsic values of gold, silver, and copper”, stated the issue 5 of Dabiq (November 2014, p. 18).

In October 2015, Al-Hayat Media Centre, ISIS media and communication department, published a video entitled “The Dark Rise of the Banknotes and the Return of the Gold Dinar”.[4] The video explained the reasons behind the creation of a Sharia-compatible currency and how it would bring about the downfall of the West.[5]

Essential to the ideology of the Islamic State is the notion of purification. Both the spiritual and physical bodies of the Khilafah must be cleansed of secular innovations and religious heresies which have been accumulated over time. In order to implement this great cleansing, al-Baghdadi’s organisation had a diverse set of policies on hand: reform of school curriculums in order to wash away the sins of modern education,[6] mass violence against populations whose religious beliefs did not fit their narrow fundamentalist template, and iconoclastic destruction of secular symbols, Shi’a shrines, ancient temples and prestigious ruins (especially those classified as World Heritage by the UNESCO).[7]

Returning to the intrinsic value of money was therefore more than a superficial policy, it was the logical consequence of the neo-Wahhabi[8] exclusivism that characterized the entire organisation. The Islamic State currency, in the same way as its government, legal practices, language and beliefs, had to be halalized, that is to say protected from impurity of speculation, virtual value[9], banking and usury, and stripped of anthropomorphic representations. It would have been, for instance, clearly unacceptable to mint the 5 gold dinar with the effigy of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (despite the fact that Omayyad coinage did depict the Caliph brandishing a sword in the period (694-697) preceding the first properly Islamic dinars).

Interestingly, the Islamic State monetary reform was not simply Jihadist eccentricity, nor was it the first attempt to resurrect a Sharia-compatible currency.

This return to the intrinsic value of money has precedents in 20th century Islamist political and economic thinking. Theologian (Indo-)Pakistani Sayyid Abdil A’la Mawdudi (1903-1979), founder of the fundamentalist Party Jemaat-e-Islami, attempted to formulate an Islamic economic alternative to capitalism and communism, articulated on 3 principles: prohibition of usury, necessity of moral supervision by Islamic authority, and collect of mandatory religious alms (zakat). The amount of zakat depends on an individual’s wealth, which should, according to Mawdudi, be calculated in gold dinar and silver dirham. Mawdudi’s considerations were not only motivated by ethical and economic concerns, but also betrayed an effort to uphold and distinguish a Muslim identity within a minority context – the Indian subcontinent before the partition (1947).[10] A similar motive was likely behind the Islamic State’s decision. In the modern Islamist forges, the dinar is first and foremost a device to materialize a religious identity. Its economic relevance is quite secondary.

In the Malaysian State of Kelatan, the Parti Islam Se-Malaysia officially introduced on August 12, 2010, a Sharia-compatible currency based on three denominations (1, 2 and 8) of gold dinar (4.25 gr. and 22 carats), along with a silver dirham.

The Kelatan dinars display on their obverse the state’s coat of arms, and on their reverse the shahâda, along with a Qur’anic verse. These coins have no legal standing but have nonetheless been introduced by their creators as an alternative currency to the Malaysian Ringgit. Apparently, this initiative has shown some success.[11] In 2011, the neighbouring State of Perak introduced its own dinars (4.25 gr. and 24 carats) and dirhams, more cautiously described as investment opportunity.[12]

Chapter II

Gold Dinars

The first prototype initially presented in 2014 by the Islamic State was made of 4.25 gr. of gold and estimated to be worth about 140 USD.[13] Below, an image of the prototype and a photograph of a coin put into circulation by the organisation between 2015 and 2016:

The engraving on the reverse is the wheat sheaf of 7 ears and represents the “blessings of sadaqah (voluntary charity)” (Dabiq 5). It refers to a Qur’anic verse: “The example of those who spend their wealth in the way of Allah is like a seed [of grain] which grows seven spikes; in each spike is a hundred grains. And Allah multiplies [His reward] for whom He wills.” [14]

The main symbol remains the same on the 2014 prototype but with a large groove added on the edge. The year is 1437 of the Hegira (i.e. between October 15, 2015, and October 2, 2016). The general aesthetic of the obverse is different but provides the same information: a circular legend identifies (on top) the Islamic State (ad-dawla al-islâmiyya) as the issuing authority, and states (bottom) “a Caliphate according to the model/method of the prophecy” (khalifaton ‘ala Minhaji Al-Nubuwwah). The same legend is found on all the coins.

The central circle contains the denomination numerals 1 Dinar flanked on each side by indication of weight (4.25 gr.) and carats (21). Those numbers are equivalent to the weight, purity (87.5%) and size (2 cm) of the first Islamic dinars produced at the end of the 7th century.

It is interesting to note that, in 2015, while the Islamic State was still announcing[15] a dinar of 21 carats, the spectrometric analysis of the 1 gold dinar specimen pictured above reveals a higher purity: an alloy composed of 91.58% of gold and 8.42% of copper, i.e. 22 carats.

Why a higher purity? Our hypothesis, further developed in the third chapter, is that the Islamic State produced a first and quantitatively modest cycle of minting, circa June-October 2015, including an unknown number of 21 carats dinars. There is circumstantial evidence that this first cycle of production included, or was put into circulation at the same time as, a number of gold-plated dinars of substantially lower quality. This predictably tarnished the reputation of the new currency and triggered a second cycle of minting.

The initial choice of 21 carats was probably not inspired by the standard of Omayyad coinage, but was due to its common usage in the Arab world. Nostalgia has its limits, as the modern and clean aesthetic of the emblematic 5 gold dinar illustrates. Indeed, nothing “traditional” to it.

The French numismatist Jérôme Jambu has also highlighted the striking similarities of the Islamic State coinage with the Saudi Halalas[16]:

This should not surprise us, as a mélange of tradition and modernity is one of the hallmarks of the Islamic State. Their ideology is a motley collection of millenarian and neo-fundamentalist ideas coddled together. Its Caliphate is a patchwork between modern statecraft and utopian fantasy, with propaganda outlets a hybrid between fashionable Vogue, entertainingly violent Counter Strike and a Salafi gazette.

In the 7th century, the monetary reform initiated by Caliph Ibn Marwan followed a pragmatic policy of currency parity with its prestigious Byzantine and Sassanid neighbours, while the Islamic State coinage aims at materializing its revolutionary utopia regardless of its financial relevance. It does look like a sort of numismatic Salafism, the dinar must abide by a catalogue of taboos and prescriptions while benefiting from a luxurious and clean design worthy of an Apple product. Alas, Salafists are not hipsters. As a stroll in Geneva’s downtown or Paris’ Champs-Elysées in July plainly reveals, an obsession of purity and fascination for some Golden Age do not necessarily imply devotion for artisanal authenticity or hand-crafted products.

The 5 dinar is allegedly composed of 21.25 gr. of gold, i.e. an approximate value of 745 USD at the time of minting. It is possible that a different version of the coin was produced by the end of 2015. Based on a design close to the 1 dinar featured above, with the same margin of diameter difference between the 1 dirham (2 cm) and the 5 dirham (3.4 cm). Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain a 5 dinar specimen[17]. Given the latter’s emblematic value and the fact that no alternative version has been so far identified, we can safely assume that the organisation chose to conserve the initial shape and engraving:

The 2014 prototype of 5 dinar features a map of the world symbolizing the universal sovereignty of the Khilafah, “including Constantinople, Rome and America”.[18]

Dirhams

The Islamic State had initially published three prototypes of silver dirhams, with a facial value of 10, 5 and 1, respectively. The 1 dirham was supposed to contain 2 gr. of silver and to feature a spear and a shield, symbols of “jihad for the cause of Allah”.

The specimen of 1 dirham we analysed differs from the 2014 prototype on several accounts: its weight is 3 gr. and it has a 99.9% of purity; the reverse, dated of 1437 AH (i.e. Oct 2015-Oct 2016), features the minaret of the Damascus Omayyad mosque (where “Issa”/Jesus will appear at the End of Times to provide support to the Muslims who remained true to the Sharia).

As illustrated below, that symbol was initially intended for the 5 dirham:

However, the version of 5 dirham put into circulation circa 2016, composed of 15 gr. of silver and 99.9% of metal purity, traded the minaret of the Omayyad mosque for the calligraphy of a Hadith relative to charity and the value of work: “The upper hand is better than the lower hand”.

The Islamic State had announced in 2014 the future minting of a 10 dirham (20 gr. of silver) and supposed to feature the Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

We have not been able to obtain a specimen or even find a photograph of the 10 dirham. Our assumption is that this coin was not part of the second and more prolific cycle of minting. It is however possible that this prototype was minted in small quantities in 2015 before the Islamic State changed the engraving (more about that later).

The 2 dirham (6 gr. and 99.9% of purity) seems to have replaced the prototype of 10 dirham, as suggested by the presence of the symbol of Al Aqsa Mosque. That engraving refers to the first qibla (direction of prayer) and to Prophet Mohammad’s sojourn from Mecca to Jerusalem, then to the Heavens and back, riding the winged steed Buraq often represented in Islamic iconography with the head of a woman and a peacock tail.[19]

Fulûs

The prototypes of 10 and 20 fils were supposed to be made of copper and serve as pocket change. Below the two models published in Dabiq in 2014, featuring the symbols of Moon Crescent referring the lunar calendar and the birth of the first Islamic state, and the palm tree which is a sacred tree in the Qur’an.

We analysed the 25 Fils, made of 20.25 gr. of copper (99.48% of purity) which, on the obverse, features the calligraphy of a Hadith “The best charity is the effort of the less wealthy”:

And the 5 Fils composed of 3.16 gr. of copper:

In 2016, the French numismatist Jérôme Jambu (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Department of Coins, Medals and Antiques) examined a 10 fils, which we believe was issued during the first cycle of minting (summer-autumn 2015). He writes that this was undoubtedly minted by coin dies made for the Near and Middle East, with a smooth cut, a reduced diameter of 19.8 mm, only weighing 2.94 gr. and not 10 gr., despite the inscription of “ten grams” (Hasharah gharamanaan) on the reverse. It is close to the coin of 2 Euro cents (19 mm for 3 gr.) and displays the same shiny aspect. Also, it is magnetic and therefore not made of pure copper.[20]

By contrast, the specimens produced after 2015 that we obtained are almost exclusively made of copper.

Chapter III

It is difficult to evaluate to which extent dinars, dirhams and fulûs were distributed and used by the populations living on the territory controlled by the Islamic State.

In a recent interview with Religioscope, an ISIS sympathizer based in Deir Ezzor, Syria, revealed that he had never seen a gold dinar. He explained they were mostly distributed by the organisation among its members in the form of wages, and commonly used to pay the dower (mahr) to the bride in the event of a marriage.

In February 2016, more than one year after the Caliphate announced its intention to retire the fiat currency to the benefit of gold and silver, activists based in Raqqa reported that the Islamic State tax collectors accepted only USD for payment of fees and charges.[21] If these testimonies are true, it clearly shows that the monetary reform was not as successful as the Caliph and its retinue expected. At the very least, the new policy was not implemented with the same diligence in all urban centres. This inconsistency might be explained by a lack of liquidity or by the population’s reluctance to convert its savings into such an unfamiliar currency, moreover one subject to rumours of fakery since 2015.

In Deir Ezzor for instance, it seems that dirham and fulûs were put into circulation (date unknown) and used as payment for taxes, fees or purchase of petrol. The new currency was gradually introduced via change offices, where the inhabitants were supposed to trade their impious money for Sharia-compatible coins if they were to be able to pay their bills or legally sell their goods. However, a number of traders and business owners had not only property and assets outside of the Caliphate’s jurisdiction, but also ongoing (and lucrative) trading exchanges with areas beyond the realm of al-Baghdadi. Dinars and dirhams had no option but to coexist with US dollars and Syrian pounds. Businesses were required to list prices only in gold or silver coins, meanwhile they still accepted payment with USD or SYP.[22]

In July 2017, al-Hayat Media Center published a video dedicated to the implementation of the new monetary system in the Caliphate’s territories. The narrator explains that despite the bombing campaign, the Islamic State had imposed the strict obligation to use the new currency for all transactions (contracts, goods and services, salaries, etc.) “everywhere the new currency is available”. The same video claimed that dinars and dirhams were already put in circulation and the fulûs were about to follow suit in order to facilitate the smallest transactions.[23]

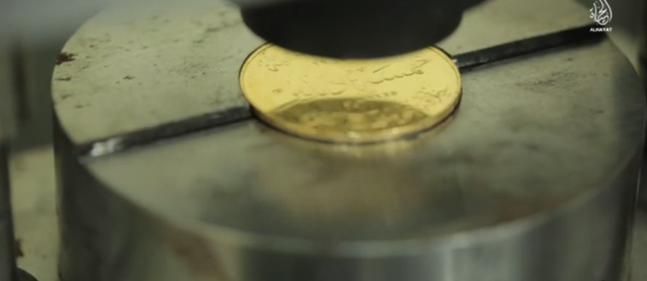

According to interviews collected by Religioscope, the Islamic State had established several minting workshops. We know from the Turkish press[24] that in 2015 a clandestine workshop was set up in Sahinbey, halfway between Gaziantep and the Syrian border. We also have evidence indicating that a striking factory was established in 2015 in Mosul, Iraq, and later was moved or replaced, possibly in Mayadin, Syria.

In March 2018, Al-Alam, an Arabic language outlet based in Iran, published a few pictures of what is described as ISIS minting equipment in Hasrat, a small village near Abu Kamal in the south east corner of Syria, recently recaptured by the Syrian armed forces[25]:

It cannot be overlooked that other workshops might have been relocated outside Syria or Iraq for security reasons, easier access to metals[26], or to secure the collaboration of experienced craftsman engraver(s).

Our interviews also revealed that at least two sets of minting equipment were used, one of them possibly imported from Italy. In the pictures published by the Turkish press following the police raid on the Sahinbey workshop in October 2015, one can identify the obverse and reverse coin dies that were used to mint the 1 and 5 gold dinars.

They are identical to the prototypes published by the Islamic State propaganda outlets:

Although the evidence may seem fragmented and insufficient, it nevertheless provides us with a plausible explanation for the different designs and shapes between the prototypes made public by the group in November 2014, those minted in Sahinbey until October 2015, and the specimens we have analysed, dated from between October 2015 and September 2017.

The authenticity of these specimens is solid, a robust body of evidence indicates that they were produced and distributed by the Islamic States in Syria and/or Iraq as of 2016. We compared several collections of coins (i.e. four sets of six coins ranging from 1 gold dinar to 5 fils, unfortunately none including the 5 gold dinar) and all collections were identical in size, weight and design and were provided by different sources based in Syria. It is worth noting, however, that only the set illustrated in this article went through a spectrometric analysis.

In September 2015, the online weekly Niqash conducted a few interviews with gold traders based in Mosul who denounced the famous gold dinars as gold-platted frauds.[27] None of the coins that J. Jambu inspected in March 2016 had their alleged metallic degree of purity. Jambu concluded at the time that if genuine gold and silver coins were indeed minted by the group in 2015, they were probably limited to a few specimens for propaganda purposes, the rest being possibly made of lower grade alloys.[28]

Either in order to preserve resources or to catch up on production delays after an announcement amid great fanfare at the end of 2014 (suggesting even Caliphates must experience bureaucratic inertia), it is not impossible that the group felt compelled to produce a first set of coins of lower quality.

There are, however, good reasons to doubt that. Given the particular emphasis put on the intrinsic value of their currency by the Caliph’s propagandists and the emblematic milestone of the return of gold dinar within their millenarian narrative, defrauding the faithful was tantamount to planting one’s scimitar in the foot. Perhaps they realized their error, initiated a second cycle of minting, and partially altered design and denominations in the process, all in a bid to restore the currency’s reputation?

The Syrian sources from Raqqa with whom Religioscope conducted interviews in the spring of 2018 explained that a substantial number of their countrymen had hoarded dinars and dirhams before quickly selling or melting them as soon as the followers of the Caliph had retreated. It is likely they also melted these down to avoid being accused as sympathizers or members of the Islamic State by the new occupying forces. Apparently, the economists of the Caliphate had forgotten Sir Thomas Grisham’s law: Bad money drives out good. In any case, hoarding or reselling would be very improbable endeavours indeed, should the majority of the coins in circulation be fourrés.

Also, in early 2018, Jenan Moussa, reporter with the Dubai-based Al Aan satellite channel, published a description and a few pictures of dirhams on her Twitter feed.[29]

In February of the same year, the review E-Sylum from the Numismatic Bibliomania Society revealed an email from James Bevan, director of Conflict Armament Research[30] which shows a few pictures of dirhams and fulûs discovered in January 2018 in Al Qaim in Iraq at a former ISIS military position.[31]

In July 2018, security forces of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)[32] raided an Islamic State cell in Jisr al-Shughur in Idlib province, Syria, and unveiled a few photographs of dirhams, along with two banknotes of 500 SYP and 10 roubles, as that cell’s leader was Chechen.

In the three cases aforementioned, the coins are (visually) identical to the specimens we obtained.

The sets we examined, and first-hand testimonies we gathered, demonstrate that dinars and dirhams were in fact put into circulation and distributed beyond the sole members of the organisation. These coins are the products of a second phase of minting whose dies’ engravings differ both from the prototypes unveiled in 2014, and from those used in Sahinbey workshop in 2015.

A first collection, congruent with the initial design (2014), seems to have been minted in the summer 2015 during what must have been a short and quantitatively modest cycle of production. A video released by al Hayat Media Center in summer 2015 introduced the first set of coins and staged their swift public issuance. In November 2015, the issue 12 of Dabiq announced that “the gold dinar coins first mentioned a year ago are now being minted, in preparation for their circulation” (p. 47). This announcement presumably alluded to the second cycle of minting, namely the very same specimens illustrated in this article.

In his analysis, J. Jambu indicates that the tweet of a Syrian activist[33] in Raqqa showing the 5 gold dinar suggested that it was produced in June 2015.[34] We, however, had to wait until October 2015 to have footage of minting and weighting, shown in the video “The Dark Rise of Banknotes and the Return of the Gold Dinar”.[35]

In January 2018, the review E-Sylum reports having received photographic proof of the existence and distribution of the neo-Caliphal currency from a gentleman fighting alongside the Kurdish forces (YPG) in Deir Ezzor. These coins appear to be identical to the sets we have examined and to the pictures shared by Jenan Moussa and James Bevan, with the notable exception of the following 10 fulûs[36] :

Given that this coin emerged alongside other specimens identical to our sets and that its market value is insignificant, one can reasonably assume it is genuine (i.e. produced by the Islamic State, although certainly in an earlier cycle of production/workshop). It is worthy to note that its symbol, the spear and the shield – here enhanced with what looks like the top of a bow – is very close to the 2014 prototype of the 1 dirham.

Conclusion

How many plated coins issued by possibly more than one workshop were distributed across Syria and Iraq? Were there more than two cycles of production and which one was the most prolific? Was a first limited series minted solely for internal usage, as a token of prestige or recognition? Was the currency distributed randomly across the Caliphate’s main cities according to liquidity availability or were there perhaps a few test trials to assess how the population would react?

Alas, the Islamic State has remained silent on the details of its monetary operations and we are reduced to speculating about the different models, periods of minting, or issuance policies.

What we can say with a reasonable degree of confidence are the following points:

1. The Islamic State did mint a set of seven coins: two gold dinars, three silver dirhams and two copper fulûs, whose metallic purity was equivalent or superior to the values announced in its propaganda outlets in 2014 and probably also to the first cycle of production (mid 2015)

2. There were a minimum of two phases of minting using different coin dies:

The first was implemented in a least two workshops, respectively in Mosul, Iraq, and Sahinbey, Turkey, probably between spring and autumn 2015. All available evidence suggests that the coinage produced in this first phase were identical to, or at least closely based upon, the design publicly revealed by the group in 2014. The relative rarity of these specimens points to a quantitatively modest production, possibly discontinued due to the pervasive rumours of fraud.

A second cycle of minting, as of winter 2015, produced the set of coins featured in this article. Their design was partially altered, with the likely exception of the emblematic 5 gold dinar, while retaining the same symbolic register and identical legends. They were also produced in greater quantity, with an emphasis on metallic purity, and more generously distributed geographically.

Olivier Moos

Notes

- I.e. not Arabized or Islamized versions of the Byzantine solidus or the Sassanian drachma, but a new Islamic currency in its own right. ↑

- About kitsch in contemporary jihadist subculture, see (in French) Le Jihad s’habille en Prada (The Jihad Wears Prada), Cahier de l’Institut Religioscope, 14, August 2016 – https://www.religioscope.org/cahiers/14.pdf ↑

- See William McCants, The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State, St. Martin’s Press, 2015. ↑

- https://jihadology.net/2015/10/11/new-video-message-from-the-islamic-state-the-dark-rise-of-banknotes-and-the-return-of-the-gold-dinar/ ↑

- For details of this brilliant plot, see John H. Cantlie, Dabiq 6, December 2014, p. 59. ↑

- As of August 2014, the group decided to purge the school curriculum of all impious material, such as music, art, civic education, social studies, history or philosophy. In February 2015, a new school manual for primary and secondary schools was distributed. It contained six subjects: the first and by far the most important was dedicated to Muhammad Abdul al-Wahhab’s (1703-1792) study of monotheism (179 pages), followed by 30 p. on the study of Arabic and English language respectively, 64 p. for mathematic, 25 p. for physics and chemistry, and 37 p. for biology. See: Laurie A. Brand, “The Islamic State and the politics of official narratives”, in Monkey Cage Blog, The Washington Post, 8 Septembre 2014 – http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/09/08/the-islamic-state-and-the-politics-ofofficial-narratives; http://www.syriahr.com/en/2015/02/is-distributes-its-own-new-curriculum-in-the-city-of-al-mayadin/ ↑

- For a detailed analysis of Islamic State iconoclasm (in French), see Iconoclasme en Jihadie : une réflexion sur les violences et destructions culturelles de l’État Islamique, Études et Analyses, Religioscope, 2015 – https://www.religion.info/pdf/2015_12_Moos.pdf. See also the excellent blog: https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/ ↑

- On the similarities between Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabism and the Islamic State ideology, see Alastair Crooke, “You Can’t Understand ISIS If You Don’t Know the History of Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia”: www.huffingtonpost.com/alastair-crooke/isis-wahhabism-saudi-arabia_b_5717157.html; Madawi Al-Rasheed, “The Shared History of Saudi Arabia and ISIS”, in Hurstpublisher.com, 28 November 2014: hurstpublishers.com/the-shared-history-of-saudi-arabia-and-isis; Cole Bunzel, From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State, The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World, Analysis Paper 19, March 2015. ↑

- Prohibition that apparently does not apply to digital currencies. A few reports have revealed the attempts by ISIS sympathizers and members to use Bitcoins in order to bypass the legal restrictions on money transfer or donation to the cause of jihad. The website isiscoin.com (now offline) offered at the end of 2017 to purchase the 7 coins set (2 gold dinars, 3 silver dirham and 2 copper fulûs) for 950$, payable with Bitcoins. Impossible, however, to assess if this website was set up by members of the Islamic State or by enterprising collectors.See Eitan Azani and Nadine Liv, Jihadists’ Use of Virtual Currency, IDC Herzliya International Institute for Counter-Terrorism’s (ICT), January 2018. ↑

- Ian Oxnevad, “The caliphate’s gold: The Islamic State’s monetary policy and its implications”, in The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2016, pp. 128 and following. ↑

- https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2010/08/12/kelantan-launches-gold-dinar; https://www.thenational.ae/world/asia/malaysians-welcome-gold-dinars-and-silver-dirhams-1.594950 ↑

- https://www.ahamedkameel.com/dinar-perak-vs-dinar-kelantan/ ↑

- In spring 2018, the 1 gold dinar could be bargained in Northern Syria for about 500$, a bit over 3 times its value on the gold market at the time. Speculation, it appears, is a vice difficult to eradicate. ↑

- Quoted by Jérôme Jambu, « DAECH, la monnaie comme arme », Association Français d’Histoire Économique, 10 March 2016, https://afhe.hypotheses.org/8669. ↑

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THSJmOEuPQw ↑

- J. Jambu, op. cit. ↑

- And so, ironically, due to its inflationary price: about 2,800$ for a single coin in February 2018. Of course, it is a vague estimation based on the average price asked for by a couple of sellers. Although this is mostly anecdotal, one of them pretended to adjust his price to the average value of gold coins looted on archaeological sites and sold on antiquity markets in Idlib Province. We verified that information in the spring 2018 and it appears to be correct. A vast array of Byzantine, Hellenistic and Arab gold coins are being sold at the time for prices corresponding, on rough average, to the price asked for the Islamic State 5 gold dinar. ↑

- Islamic State video announces minting of new currency, summer 2015 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THSJmOEuPQw, 0.50 min. ↑

- It is worth noting that featuring Al Aqsa has nothing to do with Palestinian nationalism, which occupies a very modest place in the Islamic State’s narrative. A few articles and a video “Breaking of the Borders and Slaughtering the Jews – Wilāyat Dimashq” (end of 2015) encouraged Palestinians to attacks Israel, but the objective was to capitalize on the media momentum around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and not to support a nationalist cause by definition unholy and illegitimate. Both Palestinian secular and (even more) Islamist political formations were equally despised and condemn. Cf. https://jihadology.net/2015/10/22/new-video-message-from-the-islamic-state-breaking-of-the-borders-and-slaughtering-the-jews-wilayat-dimashq/ ↑

- J. Jambu, op. cit.↑

- http://www.slate.com/blogs/the_slatest/2016/02/16/isis_will_only_accept_payment_in_u_s_dollars.html ↑

- Religioscope interviews, Deir Ezzor, June and July 2018. ↑

- https://www.memri.org/tv/isis-video-highlights-group-enforcement-of-currency-system/transcript ↑

- https://www.dailysabah.com/investigations/2015/10/07/6-arrested-for-minting-coins-for-isis-press-moulds-seized-in-southeastern-turkey; http://www.coinbooks.org/esylum_v18n41a21.html ↑

- http://www.alalam.ir/news/3426151/صور-خاصة—الكشف-عن-معمل-لصك-عملة-داعش-المعدنية ↑

- J. Jambu raised the issue of metals supply to produce enough liquidity in order to cover such a vast and populated area, in a period of high prices for precious metals, with in addition blockades implemented by armed groups fighting against the group. The author also points out that the gold bullions looted in the Iraqi central bank of Mosul (about 200 kg) would only have been sufficient to produce a mere 54,000 pieces of 1 gold dinar. See J. Jambu, op. cit. ↑

- http://www.niqash.org/en/articles/economy/5097/Islamic-State-Release-Their-Own-%27Fake%27-Currency.htm ↑

- Op. cit. ↑

- https://twitter.com/jenanmoussa/status/881230624366972928 ↑

- http://www.conflictarm.com ↑

- “New Images of ISIS Coinage”, in The E-Sylum, Vol. 21, No. 5, 4 February 2018, Article 24. http://www.coinbooks.org/v21/esylum_v21n05a24.html ↑

- Currently the most powerful Islamist coalition in the province, created officially in January 2017 and including one of Al Qaeda franchises in Syria, Jabhat Fatah as-Sham, along with a collection of factions of the same ideological ilk (such as Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zinki or Liwa al-Haqq). ↑

- Tweet of 22 June 2015 from Abu Ibrahim Raqqawi (pseudonym). France TV Info, “Daech met en circulation sa propre monnaie, le dinar”, 23 June 2015; Euronews, “Premières photos du dinar islamique, la monnaie de DAECH”, 24 June 2015. ↑

- J. Jambu, op. cit. ↑

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THSJmOEuPQw ↑

- “New Images of ISIS Coinage”, in The E-Sylum, op. cit. ↑