Introduction

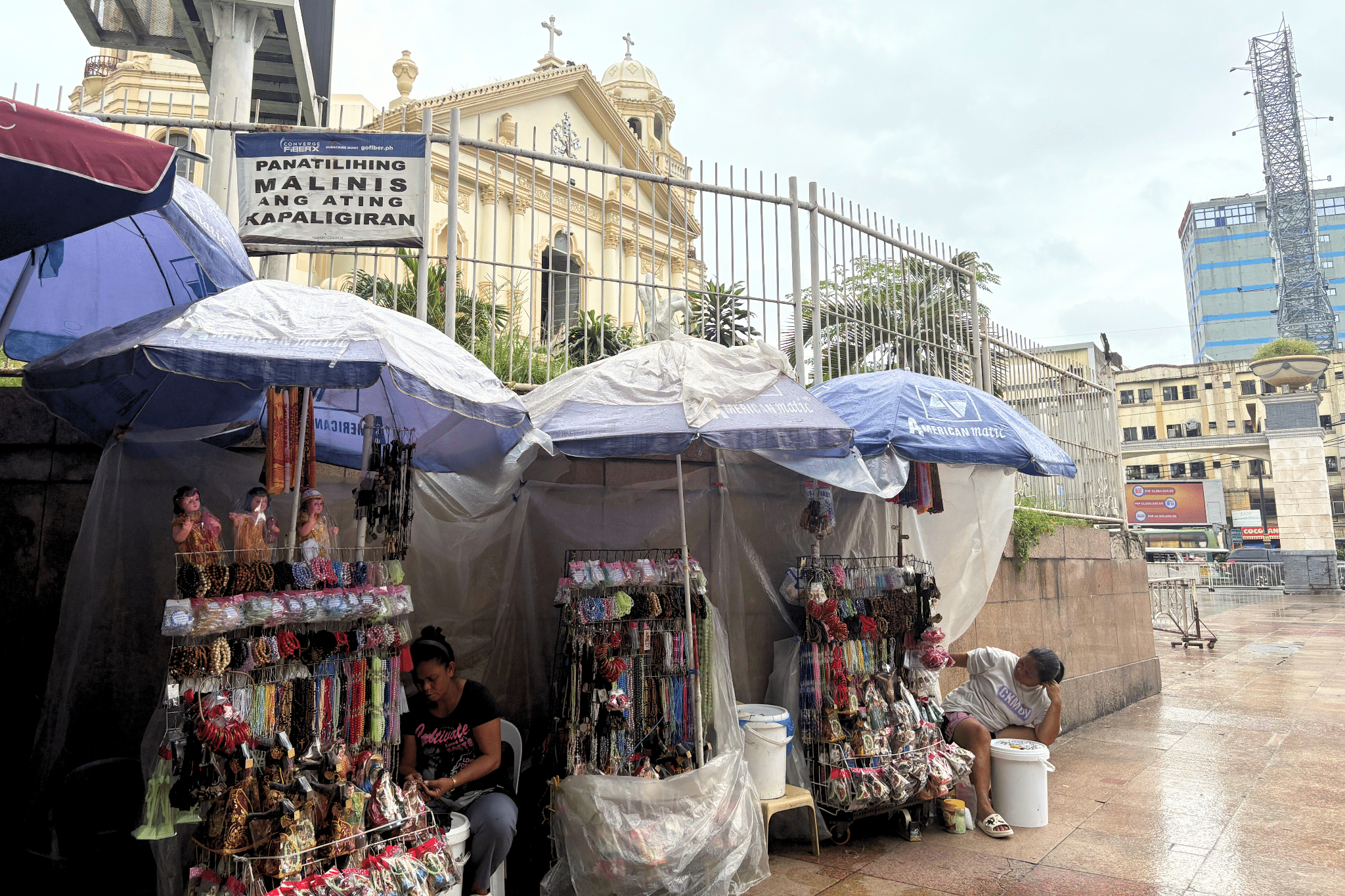

The Jesus Nazarene, or Hesus Nazareno, is a dark wooden, life-size image of Christ housed in the Minor Basilica and National Shrine of Jesus Nazareno, located in the district of Quiapo in the city of Manila, Philippines. Bearing the holy image, the site has become a global pilgrimage destination for Catholic Filipinos, transforming its peripheries into both a religious space and a hub of commerce that caters to devotees and seekers of miracles, whether occult or divine.

Previous studies on the Minor Basilica and the National Shrine of Jesus Nazareno have mostly focused on the devotion to the holy image. Some scholars have examined the different approaches to expressing one’s devotion to the holy sculpture,[1] such as through religious materiality,[2] other bodily rituals, like the annual Traslacion,[3] and the manifestation of syncretism and plurality in these devotional practices.[4] A few more articles, on the other hand, looked at Quiapo as a market or a center for commerce.[5]

Regardless of the rich literature about the site, only a few examined the entanglements between the materiality of the devotion to the Jesus Nazarene and its commodification. In this article, I argue that this commodification, manifested in the mass production and selling of religious articles associated with the holy image around the church’s peripheries, contributes to the making of everyday authenticity, that is, the devotees’ everyday practices and experiences of the sacred.

Through participant observation, interviews, and review of the relevant literature, this article investigates how the culture of devotion to the Jesus Nazarene played a role in the commodification of religious materials within the fringes of the church. Closely examining these religious articles, this paper discusses how religious commodification has reshaped the cultures of devotion to the Jesus Nazarene, producing new forms of practices and expressions of devotion.

Fieldwork for this article took place in November 2022, with verbal consent obtained for interviews and photographs. To protect anonymity, interlocutors remain unnamed, and some details are filtered, except for John Brian, who permitted the use of his real name. The analysis also draws on online sources, including YouTube videos, Facebook, and blog posts.

The devotion to the holy image of the Jesus Nazarene

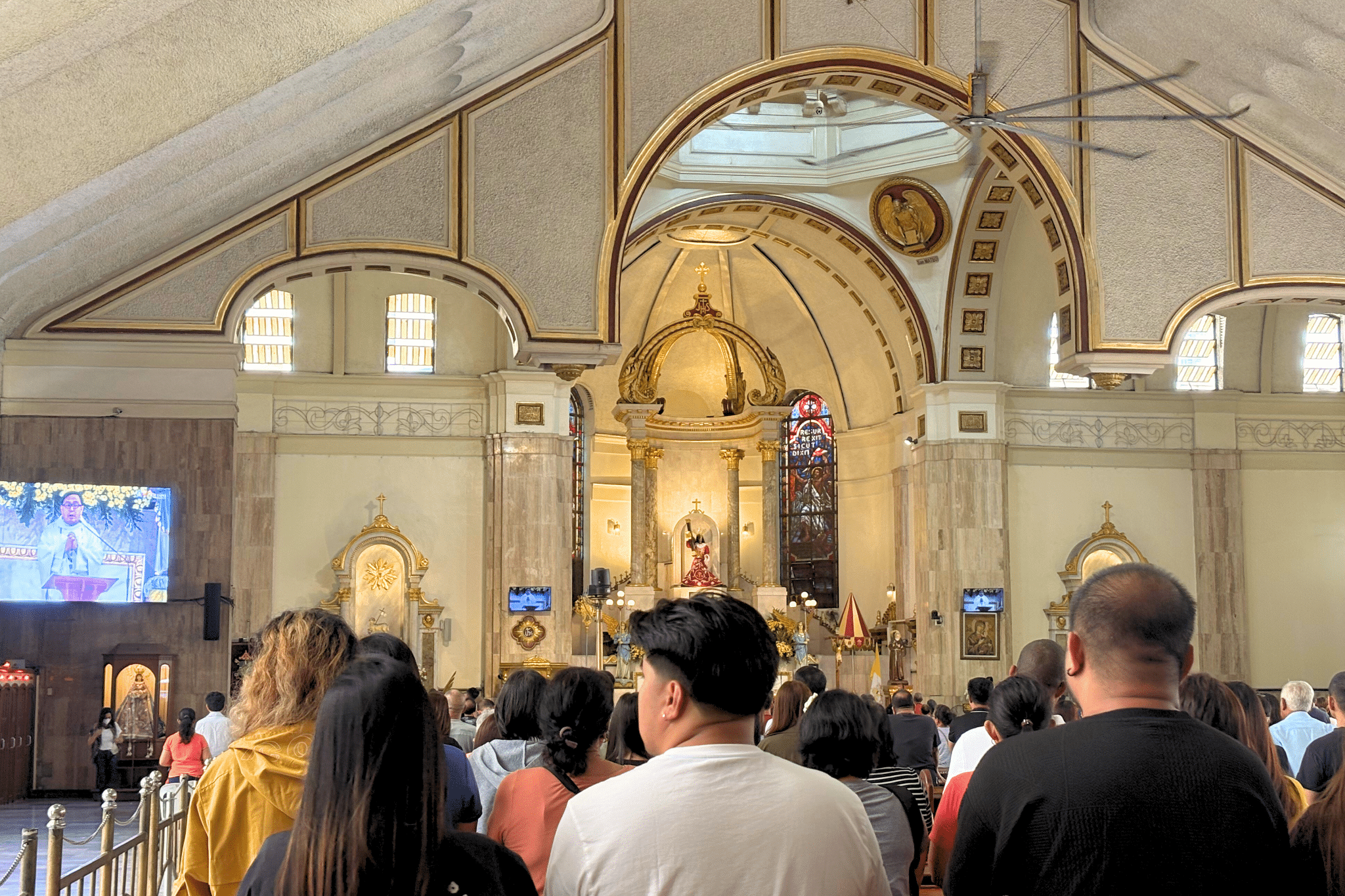

The Minor Basilica and National Shrine of Jesus Nazareno, canonically known as the Parish of Saint John the Baptist and popularly known as Quiapo Church, is home to the dark life-size sculpture of a kneeling Jesus Christ, portraying the suffering of Christ.

The image wears a crown of thorns and a diadem with three rays, and carries a black wooden cross.[6] In the church, the icon is displayed on an altar with N.P.J.N inscribed below, which stands for Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno, one of the many names of the image. Other titles include Mahal na Poong Hesus Nazareno, Mahal Na Poong Señor Nazareno, Poong Itím na Nazareno, and even shorter versions of these, such as Itim na Nazareno, Poong Nazareno, Señor Nazareno, or simply Nazareno.

The history and origin of the holy image itself are quite unclear due to the lack of historical records tracing its beginnings. Published on the official website of the church, it is said that the statue was brought to the archipelago through the Galleon trade, the first transpacific maritime route connecting Manila to Acapulco (1606), where it was first enshrined in the Recoletos Church at Bagumbayan, now Luneta.[7] Other stories of origin describe the black color to be from a fire on the ship that carried the image from Mexico. This, however, was debunked by late Filipino priest and theologian Sabino Vengco, who argued that the statue’s revered black color came from the mesquite wood used in its construction.[8]

In 2007, the church celebrated the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Jesus Nazarene in Manila.[9] However, the devotion to the Jesus Nazarene was said to have officially begun when the Cofradia de Jesus Nazareno was established in 1621; the formation is a fraternity of men in Manila that were bound by their strong devotion to the image.[10] Now, four centuries later, the devotion to the holy image continues to grow. With Filipinos coming to the Quiapo Church to visit the image of the Jesus Nazarene to become witnesses and to take part in its miracles, the site became a “center for pilgrimage”[11] in the country.

Individuals go out of their way to visit Quiapo to participate in devotional rituals or practices tied to the Jesus Nazarene. Among these traditions are kissing or touching of the image (Pahalik), changing of the garments of the sculpture (Pabihis), attending Novena prayers and masses (Pagnonobena), sprinkling of holy water after the mass (Pabendision), and the annual procession commemorating the image’s transfer to Quiapo Church (Traslacion). These practices, however, have been criticized by other Christians for bordering on idolatry. Former Quiapo Church rector, Rev. Msgr. Jose Clemente F. Ignacio, writing on the Church’s official website, draws on Victor and Edith Turner’s anthropological concept of liminality to interpret the devotion to the Black Nazarene: “The threshold of a physiological or psychological response… where the pilgrims experience distance and release from mundane structures… and receive liberation, undergoing a direct experience of the sacred, either in the material aspect of miraculous healing or in the immaterial aspect of inward transformation of spirit and personality.” Further, they argued that ordinary people generate their own liminality, particularly through the pilgrimage experience, where sites are believed to have had miracles happen and where they may get in touch with the divine and share this experience of the sacred with other people.[12]

John Brian has been a devotee for 12 years and would travel more than 100 kilometers to visit Quiapo from Laguna and participate in the Traslacion with his mother and godmother. Devotion has become a family tradition; even when the procession was suspended in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they continued to participate in some of the activities of the Church to show their devotion to the Nazareno, such as attending mass in Quiapo during the Feast of the Nazarene. For them, Quiapo during the Feast is a gathering place where devotees, many barefoot, seek blessings from the holy image, whether by touching the rope that pulls the carriage transporting the Nazareno, wiping the icon with a handkerchief, or being blessed after the mass.

As explained by Rev. Msgr. Ignacio, and as expressed by John Brian, it is through their pilgrimage to Quiapo that everyone can experience the divine with people who share the same devotion to the Nazareno, strengthening narratives of miracles and healing through traditions wholeheartedly observed.

The Commodification of Devotion to the Nazareno

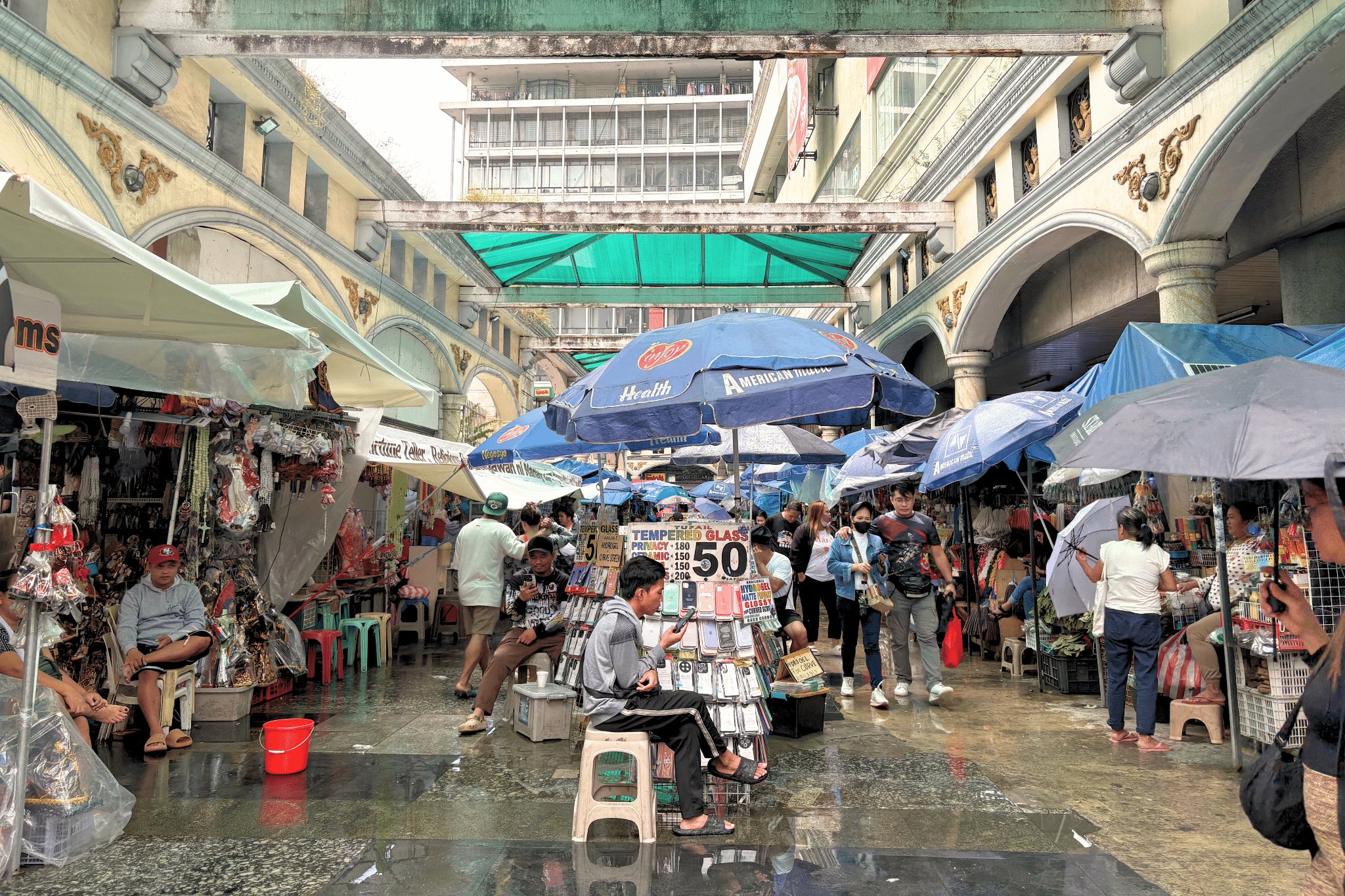

Quiapo is equally known as a commercial hub, with products ranging from optical clinics to ready-to-wear clothes, and to motorcycle parts dealers. Scholars have also examined the market for religious articles, folk medicine, and the “occult,” and other products and services outside the church.[13] Calano, for instance, explored the dialectic relationship between the faith to the Nazareno (pananampalataya) and hanapbuhay, or livelihood, showing how devotion and commerce mutually reinforce one another in constructing Quiapo as both a sacred and economic space.[14]

This interplay is most evident in the commodification of the devotion to the Nazareno, transforming Quiapo into what it is today—a place where different kinds of devotion to the sacred, even profane, are allowed to prosper. Such commodification is reflected in the market of religious articles sold at low prices outside the church and along the sidewalks. The devotional culture surrounding the Jesus Nazarene has fueled both the demand for items, such as the handkerchiefs used to wipe the holy image, and their mass production, thus embedding the sacred within everyday commodities and consumption.

Objects associated with the sacred space of the church or with the Nazareno itself have likewise been commodified. Among the concerns addressed by Quiapo Church were the selling of oils that were used for cleaning the Nazareno, as well as the dried sampaguitas offered in the church—items that some enterprising individuals sold to devotees for profit.[15]

John Brian shared that, for every Traslacion, his family bought handkerchiefs bearing the image of the Nazareno from vendors just outside the church. These were then blessed by tossing them to the devotees riding the carriage, who wipe them on the holy statue before throwing them back to the crowd. Alternatively, the handkerchiefs were sprinkled with holy water after mass. Over the years of being a devotee, John Brian has collected more than eight blessed handkerchiefs that are displayed in his house’s altar, along with a pocket-sized picture of the Jesus Nazarene. Other people also ask his family for these handkerchiefs for their own altars, like when their mother gave a blessed handkerchief to “guide” a relative who was going abroad.

Aside from handkerchiefs, other devotees also purchase miniature statues of the Nazareno to put in their own homes or as “remembrance” or “souvenirs.” Rev. Msgr. Ignacio explained that devotees want to see or feel the image of the Jesus Nazarene in their homes, whether through a replica of the holy image, a rosary, a handkerchief, or through dried sampaguitas from the church. Rev. Msgr. Ignacio further stated that devotees “believe that the shrine is a holy place and that objects that touched that holy place—whether sacred statues or ornaments in the church—would somehow bring the presence of the divine into their homes… the people want to be connected to the Divine, whether it be through the lining up for the Pahalik; or holding on to the vestments of the Jesus Nazarene after the Pabihis; or to be able to touch the rope and put it on their shoulders. This is a way of expressing one’s faith. It is an expression of their devotion.”[16]

During my visits to Quiapo Church, I also observed the sale of items not sanctioned by the Church, such as amulets (agimat), lucky charms, and herbal medicines. Conversations with vendors revealed that these goods often attracted more inquiries and purchases than traditional articles approved by the Church. An example of this is a family with a young boy from Isabela, about 400 kilometers away from Quiapo, who bought puwera usog bangles, a bracelet with oil, rope, and beads enclosed in plastic. The bracelet is believed to protect the child from harm brought by strangers (usog). They even bought five more bracelets to give to their relatives back home.

I also noticed a young woman asking if the vendor had sungay ng usa, or deer horn for curing rabies, and another woman who looked for a Niñong Hubad, literally translated as “naked Santo Niño,” something similar to a “love charm” (gayuma). Other items on display include lucky charms based on Chinese zodiac or astrology, a wide array of herbal medicines, and miracle or all-cure essential oils. There is clearly a market for a vast array of spiritual and religious items, along with the articles approved by the church.[17]

The Making of Everyday Authenticity in Quiapo

Cornelio coined the term “everyday authenticity” to describe expressions of Catholic practice that bypass institutional orthodoxy. In the case of Nazareno devotees, this is evident in participation in religious activities like the Traslacion; for others, it manifests in the possession and use of amulets or other religious objects.[18] Calano echoes this perspective, arguing that devotion to the Jesus Nazarene is rooted in everyday experiences of the sacred, forming a lived and experimentally authentic faith, even if not primarily mediated through formal ecclesiastical structures.[19] To a certain extent, commodification actively shapes and sustains the everyday experience of faith. In Quiapo, the proliferation of religious objects, often cheap, mass-produced, and sold outside the church, facilitates access to the sacred and allows devotees to apprehend it in tangible form.[20] These items foster individualized devotion and enable believers to carry the sacred into their homes and onto their bodies, thereby bridging faith and material culture. Unavoidably, Quiapo is also a stigmatized religious space. Folk practices, black candles, and amulets are frequently dismissed as occult and lying outside the bounds of the church. During my visit to the area, some interlocutors warned that religious items sold outside the church might harbor “evil energy” or be tainted by folk magic. Still, devotees purchase them. Whether blessed by priests or sprinkled with holy water by laypeople, these objects are vehicles of belief, empowering devotees to negotiate with tradition and orthodoxy, to navigate—and at times, resist—their social realities. Indeed, Quiapo Church does not fully endorse all these practices but has nevertheless made space for them.

Priests at Quiapo Church attempt to understand these expressions of faith and accommodate them in the hope of reaching the soul of the devotees and drawing them closer to God.[21] In particular, religious articles bought by the devotees are accommodated through practices of blessing and ritual incorporation: after each mass, a prayer of blessing is said by the priests, dedicated to the articles brought to the church, and the church’s prayers reviewed to attune them to the devotees. They have also initiated a liturgy or rituals for the Pabihis that conclude with the devotees touching the worn garments of the Nazareno. Moreover, the rope used in Traslacion is also packed into small strands by the church and given for free to the devotees because others go to the lengths of biting into the rope during the procession.[22] The Church seeks to reframe popular religiosity within a broad Catholic moral and sacramental framework rather than excluding it outright.

Despite the aforementioned accommodations, some practices remain outside of both the teachings of the Catholic Church and the forms of mediation sanctioned by Quiapo Church. Among these are the amulets or “anting-anting,” believed to hold supernatural power, as well as the black candles sold just outside the church precinct.[23] However, this lack of formal acceptance does not prevent churchgoers from purchasing such items and from devising informal means to have them blessed. Vendors, for example, told me that amulets could still be blessed; other churchgoers immerse the articles they buy in holy water at the entrance of the church, while others have the articles sprinkled with holy water after mass.

Conclusion

Although Cornelio speculates that commodification might pose a threat to religious authenticity,[24] there is good reason to think the opposite: commodification can facilitate religious piety[25] and contribute to animating culture change. Devotion to the Nazareno illustrates how commodification may enhance rather than undermine religious authenticity. As demand for religious articles grows, so do their production and accessibility. In turn, both clergy and laity develop ways to integrate these items into religious life and practice, thereby fueling the evolution of devotional culture. The growing devotion to the image of the Jesus Nazarene has been accompanied by a marked rise in demand for religious articles and other items of faith associated with Quiapo Church. The demand for such commodities stimulates mass production, which, in turn, makes these objects more accessible to devotees across social strata.

As the variety and circulation of religious commodities have increased, both the church and worshippers have developed different mediations to negotiate with existing social conditions, economic constraints, and doctrinal limitations. Priests bless articles brought by the faithful for a nominal fee, adapt liturgies such as the Pabihis, and distribute strands of the Traslacion rope. These efforts signal a willingness to engage with non-traditional forms of piety, even as certain items, most notably amulets, remain contested and outside the bounds of Catholic orthodoxy. Taken together, these practices contribute to the formation of a new culture of devotion, constructing authentic expressions of worship articulated around the figure of the Jesus Nazarene, the divine, and even the folk and supernatural realms. Rather than eroding authenticity, commodification thus becomes a key mechanism through which religious meaning is produced, negotiated, and lived.

Notes

- Danna Paula Olaya, “The Quiapo Church and Catholicism,” in Organized chaos: A cultural analysis of Quiapo, (Quezon City, 2013). ↑

- Mark Joseph Calano, “The Black Nazarene, Quiapo, the weak Philippine State,” Kritika Kultura, no. 25 (2015): 166–187. ↑

- Paul-Francois Tremlett, “Power, invulnerability, beauty: producing and transforming male bodies in the lowland Chritianised Philippines,” Occasional Papers in Gender Theory and the Study of Religions, no. 1 (2006). ↑

- Antonio D. Sison, “Postcolonial religious syncretism: Focus on the Philippines, Peru, and Mexico,” in The Routledge Companion to Religion and Film (London, 2009); Calano, “The Black Nazarene, Quiapo, the weak Philippine State.” ↑

- Mark Z. Saludes, “The business of devotion,” Rappler, January 8, 2015, https://www.rappler.com/nation/80108-business-devotion-black-nazarene ; Kathleen Posadas, “Quiapo on the fringe: Folk medicine and occult practices,” in Organized chaos: A cultural analysis of Quiapo, (Quezon City, 2013); Gisela Orinion, “Quiapo: Market and commerce,” in Organized chaos: A cultural analysis of Quiapo. ↑

- Minor Basilica and National Shrine of Jesus Nazareno, “Hesus Nazareno,” https://quiapochurch.com.ph/devotion/hesus-nazareno. ↑

- Minor Basilica and National Shrine of Jesus Nazareno, “Brief History of the Black Nazarene and Quiapo Church,” https://quiapochurch.com.ph/about-quiapo/history. ↑

- Jay Ereno, “Philippines’ Black Nazarene procession draws hundreds of thousands of devotees,” Reuters, January 9, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-black-nazarene-procession-draws-hundreds-thousands-devotees-2025-01-09. ↑

- Edu Punay, “Annual Nazarene feast highlights beginnings of 400-year-old image,” Philstar, January 8, 2007, https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2007/01/08/378858/annual-nazarene-feast-highlights-beginnings-400-year-old-image. ↑

- Minor Basilica and National Shrine of Jesus Nazareno, “Brief History of the Black Nazarene and Quiapo Church.” ↑

- Olaya, “The Quiapo Church and Catholicism.” ↑

- Manila Reviews, “Devotion to the Black Nazarene (A pastoral understanding)”, Minor Basilica and National Shrine of Jesus Nazareno, https://quiapochurch.com.ph/2020/12/15/devotion-to-the-black-nazarene-a-pastoral-understanding. ↑

- Saludes, “The business of devotion”; Posadas,” Quiapo on the fringe: Folk medicine and occult practices”; Orinion, “Quiapo: Market and commerce.” ↑

- Calano, “The Black Nazarene, Quiapo, the weak Philippine State.” ↑

- Manila Reviews, “Devotion to the Black Nazarene (A pastoral understanding).” ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Orinion, “Quiapo: Market and commerce.” ↑

- Jayeel S Cornelio, “Popular religion and the turn to everyday authenticity: Reflections on the contemporary study of Philippine Catholicism,” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 62, no. 4 (2014): 471–500. ↑

- Calano, “The Black Nazarene, Quiapo, the weak Philippine State.” ↑

- Julius Bautista, “Preface: Motion, devotion, and materiality in Southeast Asia”, he Spirit of Things: Materiality and Religious Diversity in Southeast Asia, ed. Julius Bautista (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012), i–x. ↑

- Manila Reviews, “Devotion to the Black Nazarene (A pastoral understanding).” ↑

- Restituto Cayubit, “Strands of ‘traslacion’ rope free for the taking,” Manila Bulletin, January 8, 2018, https://mb.com.ph/2018/01/08/strands-of-traslacion-rope-free-for-the-taking. ↑

- Manila Reviews, “Devotion to the Black Nazarene (A pastoral understanding).” ↑

- Cornelio, “Popular religion and the turn to everyday authenticity: Reflections on the contemporary study of Philippine Catholicism.” ↑

- Bautista, “Preface: Motion, devotion, and materiality in Southeast Asia.” ↑

Precious Angelica A. Echague is an early-career researcher from Palawan, Philippines. Drawing on her background in anthropology, she centers her research on notions and intersections of bodies, ecologies, and care.