In January 2025, the passing of controversial reforms to legislative powers sparked a wave of recall petitions from Taiwanese civic groups targeting Kuomintang party legislators.[1] Within months, the campaign had expanded into a nationwide debate that saw recall petitions lodged against officials from both sides of Taiwan’s political spectrum. In response, Taiwan’s Central Election Commission scheduled national recall elections for the summer of 2025, marking an unprecedented test of Taiwan’s democratic institutions amid mounting cross-strait tensions.

Civil Resistance and Legislative Crisis in Taiwan

Taiwan’s recall movement can be traced back to a series of protests in April 2024, known as the Bluebird Movement, which mainly targeted the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). Although the KMT and TPP are opposition parties to the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), together they hold enough seats in the Legislative Yuan[2] to form a majority coalition. In a bid to challenge the DPP government, the KMT and TPP pushed through several bills to expand legislative powers, limit the authority of the Constitutional Court, and channel benefits to local KMT governments. In the winter of 2024, the coalition also cut USD 6.35 billion and froze USD 7.95 billion from the central government’s proposed budget. These cuts and freezes were the largest since 2000,[3] and were criticized by the DPP as lacking sufficient justification and due process.[4]

These developments triggered strong anxieties within civil society, intertwining with fears of infiltration from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), especially after KMT leader Fu Kun-chi (傅崐萁) met with Wang Huning (王滬寧), a key policy adviser to Xi Jinping, in April 2024.[5] Growing dissent against the two opposition parties—and against the perceived shadow of China—gradually led to a nationwide recall movement, targeting a total of 31 KMT legislators. This large scale, grassroots movement eventually gained support from the DPP, and even drew criticism from the PRC’s Taiwan Affairs Office, which denounced it as “a dictatorship in the name of democracy, led by President Lai Ching-te (賴清德).”[6]

Sacred Spaces and Rituals in Taiwan’s Political Dissent

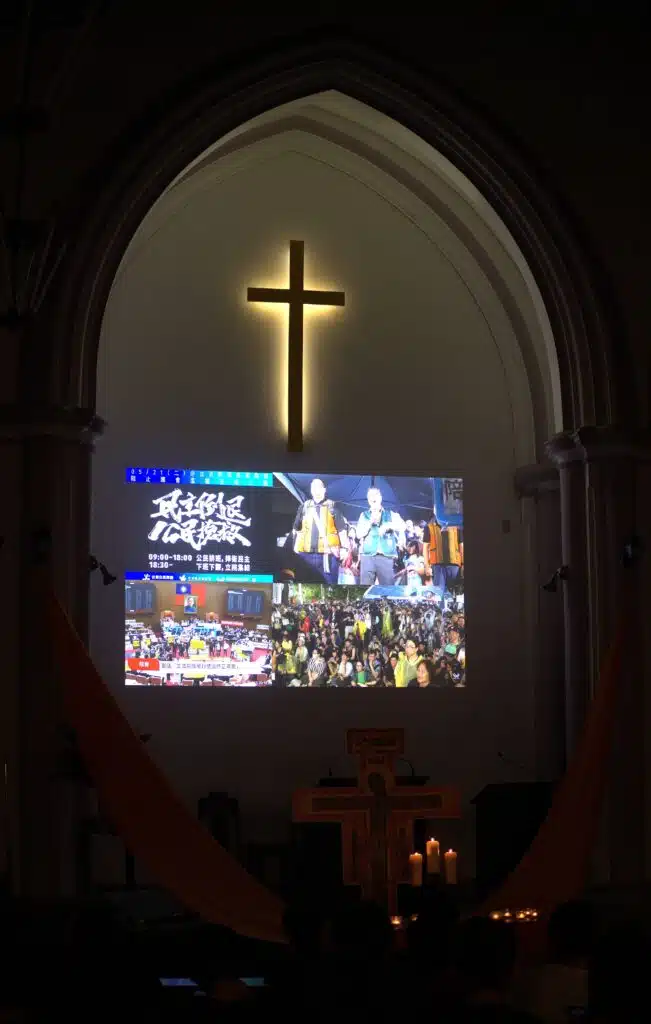

Religious institutions and practices quickly formed a key pillar, bolstering the movement’s momentum. At the very beginning of the Bluebird Movement, Che-Lam Presbyterian Church,[7] located next to the Legislative Yuan, played a key role in supporting the demonstrations. By providing food, water, raincoats, rest areas, restroom access, and even livestreams of the protests,[8] the Church effectively served as a shelter and logistical hub for demonstrators. A clergy member of the church, Ng Chhun-Seng (黃春生), cited the Latin phrase Vox Populi, Vox Dei (“The voice of the people is the voice of God”) to assert that democracy requires ongoing debate to discard choices that violate human rights and to align political paths with moral imperatives.[9] The church also became a station where civil society actors gathered for signing recall petitions.

In addition to institutional support from the Presbyterian Church, many protesters also infused other ritual aesthetics, such as memorials and funerals, to satirize political figures. These ritualized acts were aimed at symbolic denunciation of figures like KMT legislator Fu Kun-chi and TPP’s Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌). Fu faced criticism for his hard-line legislative tactics and alleged links to Chinese business interests[10], while Huang—once a figurehead of the 2014 anti-China Sunflower Movement and the New Power Party[11]—drew backlash after joining the TPP and aligning with the KMT. [12]

In Taiwan, one common curse in Han-Chinese popular religion is to treat the living as if they were already dead. This can be done through scattering joss paper with silver foil, an offering usually reserved for newly deceased ancestors and ghosts. Such curses are usually taboo, but when taboos converge with political protest, they can become a potent symbol that can mobilize across different generations.

One notable example of this is the “Master Onion Memorial (蔥師表),” a long scroll of sutra-like text consisting of many seemingly flattering phrases, mocking Huang Kuo-chang. These phrases included: “The Great Wall of Morality” (which keeps morality outside rather than within), “The Lighthouse of Freedom” (whose own foundation remains the darkest), “The Breakwater of Democracy” (which blocks the very democratic waves it claims to protect), and “The North Star of Justice” (which demands that everyone simply revolve around it).[13] At first, these phrases were only a few comments mentioned on political talk shows in mid-May. Later, people spontaneously added more epithets to these original comments. During a protest on May 24, this funeral-like atmosphere intensified: these phrases eventually developed into a sutra-like scroll, chanted among protesters.[14] Apart from the scroll, people built small altars for Huang. Some even carried long bamboo sticks, tied with soul-summoning banners, waving them in the air and shouting, “Come back home.” The banner bearer was followed by a rally holding pictures. This rite, recollecting the soul after death, is usually performed in funerals or after accidents. Several interlocutors remarked that the protest resembled an all-encompassing funeral for Huang Kuo-chang.

On May 28, the folk-rock band Tsng-kha-lang (裝咖人) performed their piece Tshut-Tsng (出庄, “[the deceased] leaving the village”), inspired by rural funeral traditions in Taiwan.[15] At its climax, the singers shouted kue-kio (“crossing the bridge”) with the crowds. At the same time, pictures of both Huang Kuo-chang and Fu Kun-chi were projected onto a screen. According to popular Taiwanese religion, this chant guides the deceased across the Naihe Bridge in hell, enabling rebirth through reincarnation. The symbolism was clear: the figure once celebrated as a hero of social movements was being declared dead alongside the very leader he once opposed.

At the end of 2024, a nationwide recall movement was launched. To gather enough signatures for the recall petitions, some local communities incorporated religious icons to attract broader support. On March 9, recall campaign groups in Taichung City publicized themselves as Huicheng Temple (慧成宮).[16] In Mandarin Chinese, the name “Huicheng Temple” is a play on words, a homophone of “it will succeed” (會成功, both pronounced as “hui-cheng-gong”). The title resonates with popular religious belief in temples, representing demonstrators’ hope that their success might bring peace and harmony to society, just as local deities in temples bring blessings to their devotees. The aesthetic feature of this aspect of the recall campaign, down to the matching caps, flags, and interior decorations of an office, all mimicked temples in Han-Chinese popular religion.[17] This wordplay was even adopted by the DPP party, such as in the slogan: Big Recall, Big Success Temple (大罷免, 大成宮). In June, DPP legislator Ke Jian-ming (柯建銘) registered the slogan as a trademark.[18]

Demonstrators also drew on elements of Daoism in their use of wordplay. A Daoist ritual expert in Nantou County drew a talisman in support of the local recall campaign. The top of the charm represents from where it derives its power: Nantou Recall Ding-Cheng Temple (南投罷免定誠宮); again, Ding-Cheng Temple, pronounced as ding-cheng-gong in Mandarin, means “definitely succeed.” At the center of the charm, the Daoist wrote: “Yu-Head and Ma-Face, begone (游頭馬面退散).” This phrase plays on the homophonic resemblance to “Ox-Head and Horse-Face,” two figures of the underworld, while using the surnames Yu and Ma to target local legislators: You Hao (游顥) and Ma Wen-Jun (馬文君). Local recall campaign soon applied this talisman to campaign giveaways, including stickers and teabag packages.

The charm represents a strong political hope with a carefully designed Daoist aesthetic: through the success of the recall campaign in Nantou, the two legislators, Yu and Ma, shall leave. Interestingly, when distributing the talisman, the ritual expert stressed that he excluded the opening strokes of Daoist talismans and fu dan (符膽, literally “talisman core”; a fu dan is an empowering inscription written at the bottom of a Daoist talisman while chanting incantations, believed to instill the talisman with divine power. This way, the charm is incomplete, and therefore not equipped with religious power. As a result, people were invited to use the charm freely without fear of offending deities.

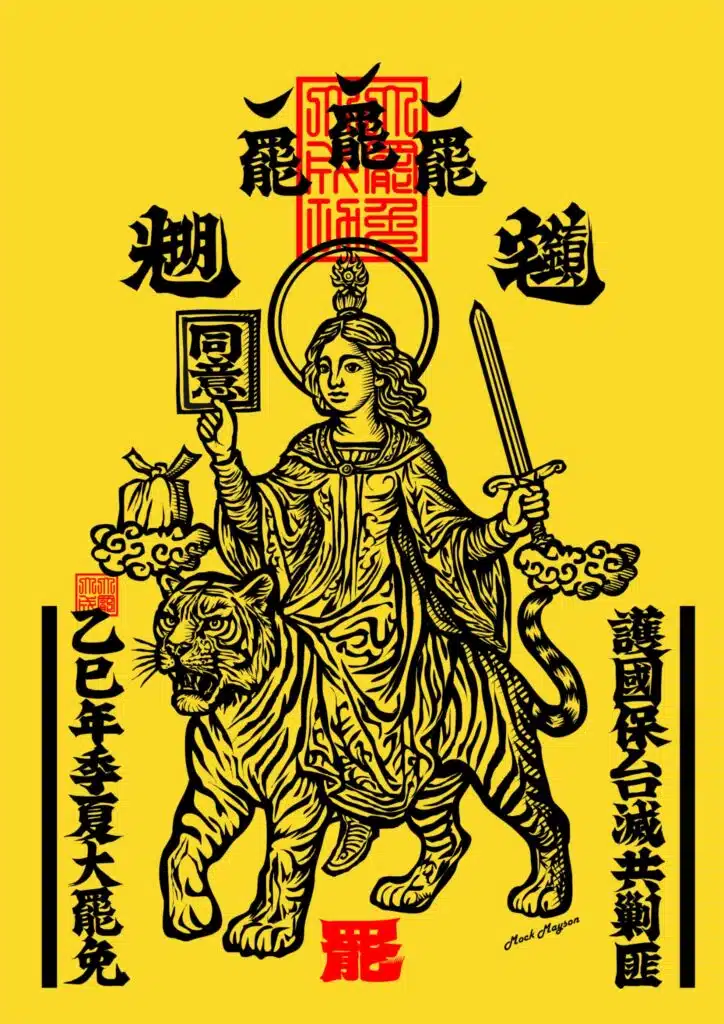

Graphic designers also used charm aesthetic to reflect their concerns about the recall movement. Designer Mock Mayson, for example, redesigned the Celestial Master’s Household Talisman (天師鎮宅符).

Traditionally, the central motif of such a talisman is the image of Zhang Daoling, the founding Celestial Master of Orthodox Unity Daoism (also known as Zhengyi Dao). In popular religion, Zhang Daoling is able to subdue spirits and demons. Thus, his power is to secure household safety and peace.[19] Mock Mayson explained his design on Facebook: “Because during this recall movement, I saw many women courageously take to the streets despite threats, I thought, why not simply change the male image of the Celestial Master into a female one?”[20]

Interestingly, Daoist ritual experts tend to carefully remove divine power from talismans, while graphic designers apply charm aesthetics more boldly, including the opening strokes of Daoist talismans and fu dan. As Mock Mayson explained his design: “At the top of the design, you can see three hooks, which represent the common opening strokes of Daoist talismans, known as the “Sanqing (三清).” The fu-dan at the bottom, usually inscribed with the “Four Uprights” (si-zheng, 四正). I changed [the opening and the bottom] to “Four Capabilities” (si-neng, 四能), which together form the character for “recall” (ba, 罷).”

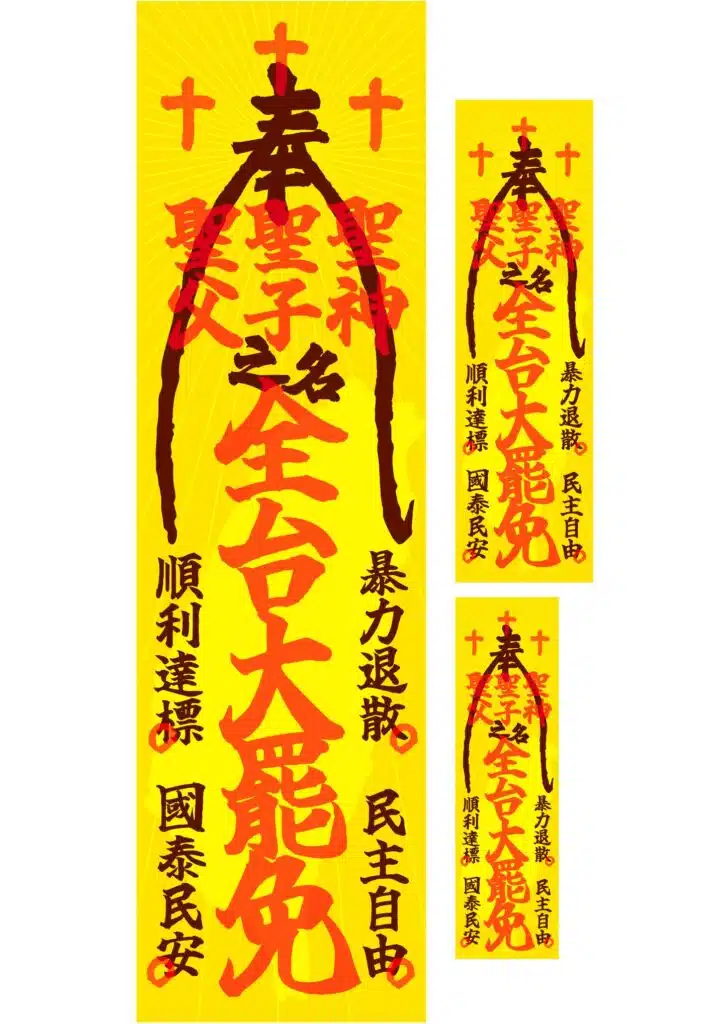

Another designer, Wei-An Wang (王偉安),[21] crafted a Christian charm for the recall campaign. He transformed the opening strokes into God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit, written in large red characters in the Daoism talismanic layout. The charm can be read in this way: “In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, we proclaim: Violence, be gone; democracy and freedom; achieve success with ease; peace and prosperity for the nation and its people. We aim for recall across Taiwan.”

By adopting the aesthetics of Daoist ritual writing while embedding Christian references, this poster creates a striking hybrid symbol: it blends Daoism (and more broadly, Taiwan’s popular religious culture) with Christian language to respond to political movements. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the design triggered discussion among Protestants regarding the appropriateness of the hybrid charm.[22]

By adopting religious aesthetics in this way, members of the public can be seen to incorporate their religious practices with their political perspectives. These perspectives fundamentally counter those of the PRC, which has long claimed that religious experiences serve to highlight the cultural connections between China and Taiwan.

Ghosts That Refuse to Fade: Faith and Resistance After the Recall

Despite protestors’ best efforts, the recall movement ultimately failed in achieving its original objective. While the KMT and the TPP were able to consolidate their partisan supporters, dissidents’ warnings about PRC influence alone could not mobilize a broader base.[23] More importantly, the KMT and TPP strategically reframed the recall as an act of sabotage against democracy, allegedly orchestrated by the incumbent DPP government.[24] This narrative, widely circulated in media and local networks, shifted public perception: what began as a bottom-up initiative to challenge legislative chaos was often successfully reinterpreted as top-down partisan infighting.[25]

In the aftermath of the failed recall, the owners of the bookstore To-uat Books (左轉有書), long active in social movements, continued with their plan to hold an event to show respect to the ghosts of those who died under the authoritarian KMT regime. Over the past few years, the bookstore had already hosted Pudu (普渡) ceremonies,[26] and 2025 was no exception. This year, they even enlarged the scale of the ceremony. The owner of the To-uat Books remarked on their Facebook page, stating the needs of such a pacifying ceremony: “Two kinds of ghosts are said to roam. The ghosts of the living: the well-dressed heirs of privilege who inherit parliamentary seats, neglect legislation, and bow to Chinese officials. And the ghosts of the dead: the students arrested for reading banned books, the poets tortured for their songs, the youth executed for dreaming of freedom, their souls still trapped without proper farewell.”[27] In other words, showing respect to the deceased and sending away the unqualified KMT legislators were combined in the same event: remember, and take action.

Nevertheless, the outcome of the vote suggested that the recall petition campaigners are still unable to send away “the ghost of the living.” On July 27, two days after the recall movement failed, the owner of the bookstore posted their thoughts on continuing the event: “What we want to say is this: in the absence of success, the need for Pudu is even greater…the purpose [of such a ceremony] was to help more people remember: remember the silhouettes of those who have repeatedly stood up through those years, and the courage to start again after each defeat.”[28]

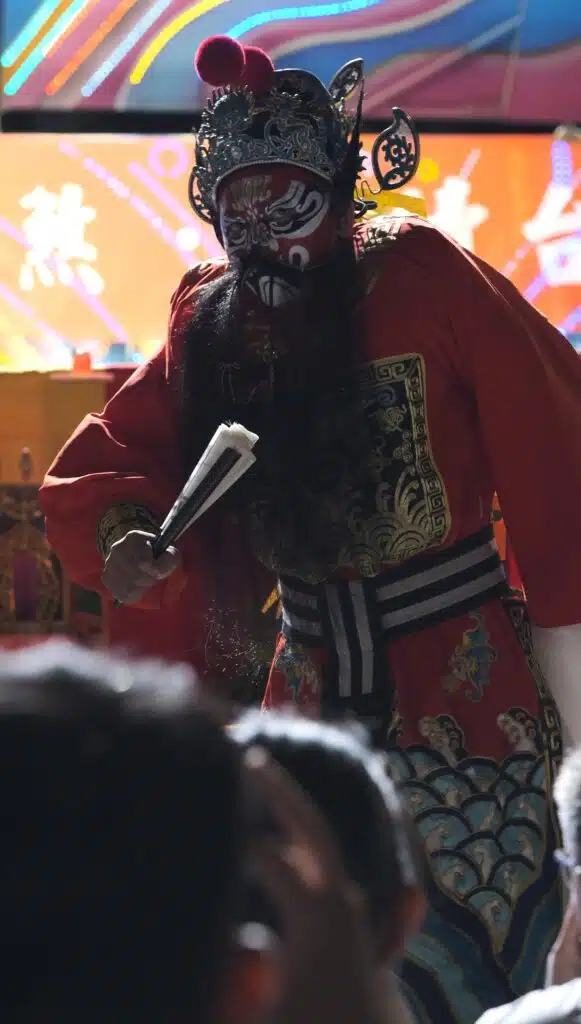

On August 30th, To-uat Books convened Taiwan’s first “Cultural Ghost Festival” at Qingdao East Road No. 3 in Taipei. The program wove together literature, poetry, testimony, and ritual, and featured Daoist ritual experts performing the Pudu ceremony. The Daoists began by solemnly worshipping their celestial masters on a red platform, before inviting the deity of savior, Taiyi Jiuku Tianzun (太乙救苦天尊, also known as Taiyi Zhenren太乙真人), to descend. They then held a bamboo stick with a banner of Taiyi Zhenren, and walked down from the platform to a table on which stood four small tablets representing the victims of the authoritarian regime prior to democratization in the early 1990s.

The Daoists, now accompanied by Taiyi Zhenren, began to chant sutras for the spirits of these victims. After the chanting, the Daoists walked back to the platform, and one Daoist, representing Taiyi Zhenren, started wearing the Wulao Guan (五老冠), a hat decorated with five elders. At this moment, the Daoist was not just a ritual expert; he had become the Taiyi Zhenren, chanting sutras while throwing offerings to the crowd, symbolizing the provision of salvation for the spirits. From a religious perspective, the deity had descended upon the site where the KMT regime once interrogated its victims, and where the KMT party’s legislators still hold their positions. Meanwhile, the ghosts of those who died under state violence were also invited to the ceremony, standing alongside the living. It was a moment when the host of the ceremony gave voice to the marginalized ghosts and the defeated recall campaigns, conveying their political concerns to the well-respected deity: they would not forget the authoritarian past, nor would they give up on the social movements of today.

After the ritual, one of the Daoists, Chen Bo-yu (陳柏瑜), remarked on social media: “I consider myself someone whose political stance is rather ambiguous, but I believe the path of great compassion embodied in the Ghost Festival can transcend any political or ethnic values. I hope this experimental work may serve as an introduction, encouraging more young people who care about social issues to look back on their own roots, take up the incense once again, and show reverence to Heaven and to their ancestors.” [29]

Chen’s remark situates a new ritual for certain ghosts in the broader context of identity and memory, transcending Taiwan’s current party politics. It echoes Taiwan’s year-long recall movement, in which religious beliefs and practices offered participants culturally resonant symbolism to voice anger, summon solidarity, and reimagine political actions. Even though the recall itself ended in failure, the persistence of Pudu ceremonies and the emergence of a “Cultural Ghost Festival” reveal how religious beliefs are able to reconfigure loss into rebirth.

Conclusion

The trajectory of Taiwan’s recall movement in 2024–2025 demonstrates that religious beliefs are constitutive forces through which meanings, aesthetics, and practices are continuously developed. By invoking funerary rites, Daoist talismans, Christian symbols, and ghost-pacifying ceremonies, participants mobilized traditions deeply embedded in Taiwan’s vibrant cultural lives to highlight their political aims and struggles. These scenes deserve careful attention, for they suggest that democracy is not only negotiated in parliamentary chambers, but also enacted in ritual spaces, on city streets, and in the memory of ghosts that refuse to fade. These practices also affirm that Taiwan’s democracy endures across multiple cultural contexts.

As the graphic designer, Mock Mayson, remarks on his Facebook page: “The cultural traditions of Taiwan’s temples, passed down from the Ming and Qing dynasties through the Japanese colonial era, are still vibrantly alive today. They remain a living faith and daily practice for many Taiwanese people, not some fossilized relic locked in a museum, nor staged set pieces with hired monks in a Communist Party–run temple.”[30]

Notes

- For a more detailed breakdown of Taiwan’s recall movement, see Bo Tedards, “Taiwan’s 2025 Recalls: A Civil Society Perspective,” Global Taiwan Institute, July 23, 2025, https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/07/taiwans-2025-recalls-a-civil-society-perspective. ↑

- The Legislative Yuan is Taiwan’s unicameral parliament, located in Taipei. It has 113 directly elected members serving four-year terms and is responsible for passing laws, approving budgets, and overseeing the executive. Under Taiwan’s current constitution, it also holds powers such as initiating constitutional amendments, presidential recalls, and impeachments. ↑

- Whogovernstw菜市場政治學, “Record-High Cuts and Freezes in the National Budget: What Are the Procedural Issues? 總預算案刪凍數目達到新高: 其中的程序問題在哪裡?” accessed September 10, 2025, https://whogovernstw.org/2025/01/25/whogovernstw12. ↑

- Yang Jun-Jie楊竣傑 et al., “Budget Passed on Third Reading: What About the NT$200 Billion in Cuts—Will Government Be Paralyzed? 總預算三讀通過: 被刪的兩千多億怎麼辦—真的會讓政府癱瘓嗎?” CommonWealth Magazine天下雜誌, January 22, 2025, https://www.cw.com.tw/article/5133848. ↑

- Chris Buckley 儲百亮, “The CCP’s Ideological ‘National Tutor’ Wang Huning: His New Task on Taiwan中共意識型態’國師’王滬寧的新任務: 台灣,” The New York Times Chinese紐約時報中文網紐約時報中文網, October 28, 2024, https://cn.nytimes.com/china/20241028/china-xi-jinping-adviser-taiwan/zh-hant; Lu Jia-Rong呂佳蓉, “Wang Huning Meets Fu Kun-chi, Says the Two Sides Should Maintain Frequent Contacts王滬寧會見傅崐萁 稱兩岸應常來常往,” The Central News Agency 中央通訊社, April 27, 2024, https://www.cna.com.tw/news/acn/202404270189.aspx. ↑

- Dong Rong-Ci 董容慈 and Li Cheng-Xin李澄欣, “Taiwan’s ‘Mass Recall’: What Happened, How Parties Responded, and How the Vote Works台灣’大罷免’事件始末: 政黨表態及投票流程等一次看,” BBC News Zhongwen BBC News 中文, July 15, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/articles/cvgwzx9erylo/trad. ↑

- The Presbyterian Church in Taiwan was established in 1865. It is the largest Protestant Christian denomination in the country. In the 1970s, the Church proactively supported several political movements against the KMT regime in Taiwan’s authoritarian era. For more details, see Kwan Yuk Sing, “The Presbyterian Church in Taiwan:Between Prophetic Tradition and Institutional Challenges,” Religioscope, September 2025, https://english.religion.info/2025/09/17/report-the-presbyterian-church-in-taiwan-between-prophetic-tradition-and-institutional-challenges/. ↑

- Li Wen-Xuan李玟萱, “One Long Take: The Man of Steady Calm—Ng Chhun-Seng一鏡到底: 恆溫的人—黃春生,” Mirror Media鏡傳媒, August 31, 2025, https://www.mirrormedia.mg/story/20250822pol001. ↑

- Chen Yi-Xuan陳怡萱, “Prayer Meeting at Jinan Church: ‘Bluebird Movement’ Supporters Gather to Call for Democracy濟南教會祈禱會: ‘青鳥行動’民眾齊聚籲民主,” Taiwan Church News Network 台灣教會公報, May 29, 2024, https://tcnn.org.tw/archives/206822. ↑

- Chen Yan-Ting陳彥廷, and You Wan-Qi 游婉琪, “Lide Resort Scandal Twist: Fu Kun-chi Tied to Chinese Land Purchases? 理想大地案外案: 傅崐萁引中資買地?” The Reporter報導者, November 21, 2016, https://www.twreporter.org/a/hualien-fu-kun-chi-china-enterprise ↑

- Li Xue-Li李雪莉, “Huang Kuo-chang in Exclusive Interview: Pension Reform Must Start Now獨家專訪黃國昌: 馬上推動年金改革,” The Reporter報導者, January 17, 2016, https://www.twreporter.org/a/2016election-kchuang-interview. ↑

- Cai Li-Xun蔡立勳, “Huang Kuo-chang: From Rebel Student to Political Influencer and Third-Force Leader黃國昌從叛逆學生變政治網紅,” CommonWealth Magazine天下雜誌, March 6, 2025, https://www.cw.com.tw/article/5134333. ↑

- Zhou Wei-Hang周偉航 (@Ninjiatext), “The epithet I gave to Huang Kuo-chang and its meaning我幫黃公國昌上的封號與意思,” Facebook, May 21, 2024, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/17KQHjXprV/. ↑

- Brian Hioe, “The Aesthetics of the Bluebird Movement,” New Bloom, May 31, 2024, https://newbloommag.net/2024/05/31/bluebird-movement-aesthetics/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. ↑

- Rachel Yip葉瑞秋, “Tsng-kha-lang: Ghosts, 228 Memories, and the Question of Today’s ‘Taiwanese’ Flavor? 樂團裝咖人: 孤魂野鬼還是二二八記憶, 什麼是我們時代的’台’味?” Initium Media端傳媒, September 22, 2022, https://theinitium.com/article/20220922-culture-zhuang-ka-ren-taiwan-band. ↑

- SETN三立新聞網, “Taichung Recall Campaign at ‘Huicheng Temple’: Recall Group Plays on the Pun ‘Huichenggong’ with Banners Listing Six Deities, Winning Public Praise as Creative—‘It Will Succeed! 台中罷免慧成宮! 台中罷團取諧音創’慧成宮’助罷免, 旗幟羅列罷免六大千歲, 獲民眾大讚: 有創意 ’會成功’!” posted March 9, 2025, YouTube video, 10:40, https://youtu.be/5NHX6PZ5RYk?si=y1CCBixPCpizYTsK. ↑

- Su Jin-Feng蘇金鳳, and Cai-Shu-Yuan蔡淑媛, “Huicheng Temple, Haocheng Temple, Qiaocheng Temple—All Join In: Taichung Recall Group Shows Boundless Creativity慧成宮 豪成宮 敲成宮攏總來 台中罷團創意滿滿,” Liberty Times News 自由時報, March 19, 2025, https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/politics/paper/1697218. ↑

- Lin Jing-Yin林敬殷, and Liu Qian-Ling劉千綾, “Registering ‘Great Recall Dachen Temple’: Ker Chien-ming Calls It a Preventive Measure註冊’大罷免大成宮’: 柯建銘預防性措施,” The Central News Agency 中央通訊社, July 30, 2025, https://www.cna.com.tw/news/aipl/202507300333.aspx. ↑

- National Museum of Taiwan History國立臺灣歷史博物館典藏網, “Celestial Master’s Household Talisman天師鎮宅符,” accessed September 10, https://collections.nmth.gov.tw/CollectionContent.aspx?a=132&RNO=2010.003.0219. ↑

- Mock Mayson (@mock.mayson), “As a matter of fact, I harbor a small personal interest 其實我個人有個小小的興趣,” Facebook, July 19, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/19p1FTb1UR/. ↑

- The creator wishes to be credited under the social media handle “_naiewgnaws.” ↑

- 黃春生 Ng Chhun-Seng, “Might Daoist talismans (fu lu) be employed as resources for an indigenized Christian theology? 符籙能否成為一種基督教本色化神學的素材?” A Pilgrim 天路客, March 29, 2025.↑

- Yeh Chia-Chun葉家均, “Taiwan’s ‘Mass Recall’: Why the Defeat, and What Pressures Lie Ahead for Lai Ching-te? 台灣’大罷免’為何慘敗? 賴清德面臨哪些壓力?” Deutsche Welle 德國之聲, July 29, 2025, https://p.dw.com/p/4yBTK.↑

- Yimou Lee, “Taiwan move to recall opposition lawmakers fails,” July 27, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/taiwan-move-recall-opposition-lawmakers-fails-2025-07-26/ ↑

- Yet attributing the failure solely to ineffective persuasion overlooks deeper issues. The recall campaign struggled with limited organizational resources, uneven local networks, and the broader ambivalence among Taiwanese voters toward recall as a democratic tool. Civil society emphasized grassroots participation and political learning, but this framing did not resonate widely. Voter responses were also diverse: while some saw the recall as a test of civic will, others accepted the opposition’s portrayal of it as destructive and divisive. ↑

- In Taiwan, a Pudu (普渡) is a traditional ritual, blending Daoism, Buddhism, and Han-Chinese popular religion. It is usually held during the seventh month of the Lunar Calendar, also known as the Ghost Month. It involves offering food, incense, and joss paper to wandering spirits and neglected souls, so they may find peace and not disturb the living. Communities often gather in temples, streets, or workplaces to perform the rite, which also expresses gratitude, charity, and the value of maintaining harmony between the human and spiritual worlds. ↑

- TouatBooks左轉有書 (@touatcafephilo2016), “For the first time in 70 years 七十年來第一次,” Facebook, August 16, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1CsY5WnyTQ. ↑

- TouatBooks左轉有書 (@touatcafephilo2016), “The Recall May Have Failed, But the Pudu Must Go On大罷免沒成功, 我們更要普度,” Facebook, July 27, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/14M6wA3vy9c/. ↑

- Chen Boyu陳柏瑜 (@brian.chen.773776), “Afterword後記,” Facebook, September 2, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1BajXRhFYs/. ↑

- Mock Mayson (@mock.mayson), “As a matter of fact, I harbor a small personal interest 其實我個人有個小小的興趣,” Facebook, July 19, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/share/p/19p1FTb1UR/. ↑