From Chile to Taiwan: Becoming Mrs. Tsai

Elvira grew up in a Catholic household in Chile. In the 1980s, she met Taiwanese businessman Mr. Tsai (蔡) in Brazil, where he was traveling for work. Mr. Tsai was to return to Taiwan shortly after they began dating, and Elvira chose to accompany him, even though neither she nor her family knew where Taiwan was located.

The couple settled in Dacheng Township (大城鄉), Changhua County, a farming town in the central-west part of Taiwan. Then, as today, residents of Dacheng Township mainly relied on agriculture for their livelihood, growing crops such as watermelons, peanuts, and rice. Due to its strong traditional culture, temples are an integral part of villagers’ lives. Whether they are sick, experiencing bad luck, feeling lost in life, or simply wanting to chat with others, temples can be a central space for communal life.

Within Dacheng village, Mr. Tsai served as the biō-kong (廟公) of Wan’an Temple (萬安宮), overseeing the sanctuary’s maintenance and leading ceremonies dedicated to its main deity, General Fushun. Several versions of General Fushun’s story circulate, but at Wan’an Temple he is identified as Ma En (馬恩, also known as Ma Bo Chiao, 馬伯喬), a general who served Emperor Renzhong (宋仁宗, r. 1010–1063) of the Northern Song dynasty and was ultimately framed by ministers and executed.

As biō-kong, Mr. Tsai was busy at specific times. On the 1st and 15th day of every month in the lunar calendar, believers would come to the temple and pray for the protection of General Fushun. To prepare for temple activities, Mr. Tsai would need to get up before sunrise and open the temple’s gate.

For Elvira, this all came as a shock. Accustomed to the familiar atmosphere of Catholic churches, she found herself struggling with the thick cloud of incense smoke, and was unsettled by local customs, like ti-kong (神豬、豬公), ritual pig-raising and sacrifice during temple festivals. When a temple hosts an event, like the birthday of deities, villagers would sacrifice the animals they feed, such as chicken, fishes, and pigs. Before an event, villagers will deliberately raise swine to grow to a large size and compete to see whose pig is the largest and the heaviest. The winner, it is believed, earns abundant good fortune, while the contest itself is also an act of reverence and gratitude to the deity. When Elvira first joined the event, she was both startled and intimidated by the large pigs: “I have never seen such a big pig!” she told Religioscope.

Still, she gradually began helping her husband and learning about Taiwanese folk practices. At the same time, she sought a Catholic church in Dacheng to continue to practice her faith, without success.

From Mrs. Tsai to Biō-Pô: A Turning Point

In 2002, Elvira’s life changed abruptly when Mr. Tsai died in his sleep. Their new house had just been completed, their two sons were only 10 and 12, and Elvira was left without family nearby. She considered returning to Chile, but villagers urged her to stay. After consulting General Fushun, she decided to remain and stepped into the role of biō-pô.

The first hurdle for Elvira was language. Without her husband’s translations, she had to communicate on her own. Local elders spoke only Taiwanese, while her sons’ schoolwork was in Mandarin. Elvira bought audiotapes, studied alongside her children, and improved quickly with the support of the community.

Ritual practice as biō-pô brought further challenges. During siu-kiann (收驚), a ritual meant to recall lost souls performed on individuals who believe themselves to be pursued by evil spirits, she was told to wear all black. For Elvira, this clashed with her own cultural background, where black was reserved for funerals and carried connotations of mourning or even foreboding in other contexts. Festival offerings also shocked her: the sheer abundance of vegetables, fruits, and sacrificial animals displayed to honor and express gratitude to the deities dwarfed anything she had seen before.

Yet, despite the cultural dissonance, Elvira came to feel General Fushun’s protection and guidance when she was adrift. “I put Jesus and the Lord in my heart, but I believe that all faiths seek peace and safety, and that is why I serve General Fushun now,” Elvira confided. Other experiences have also strengthened her faith, with Elvira crediting Fushun’s help in curing ailments and offering protection within the community. Serving the temple as biō-pô had become her way to safeguard both her family and her new home.

Days in Wan’an Temple

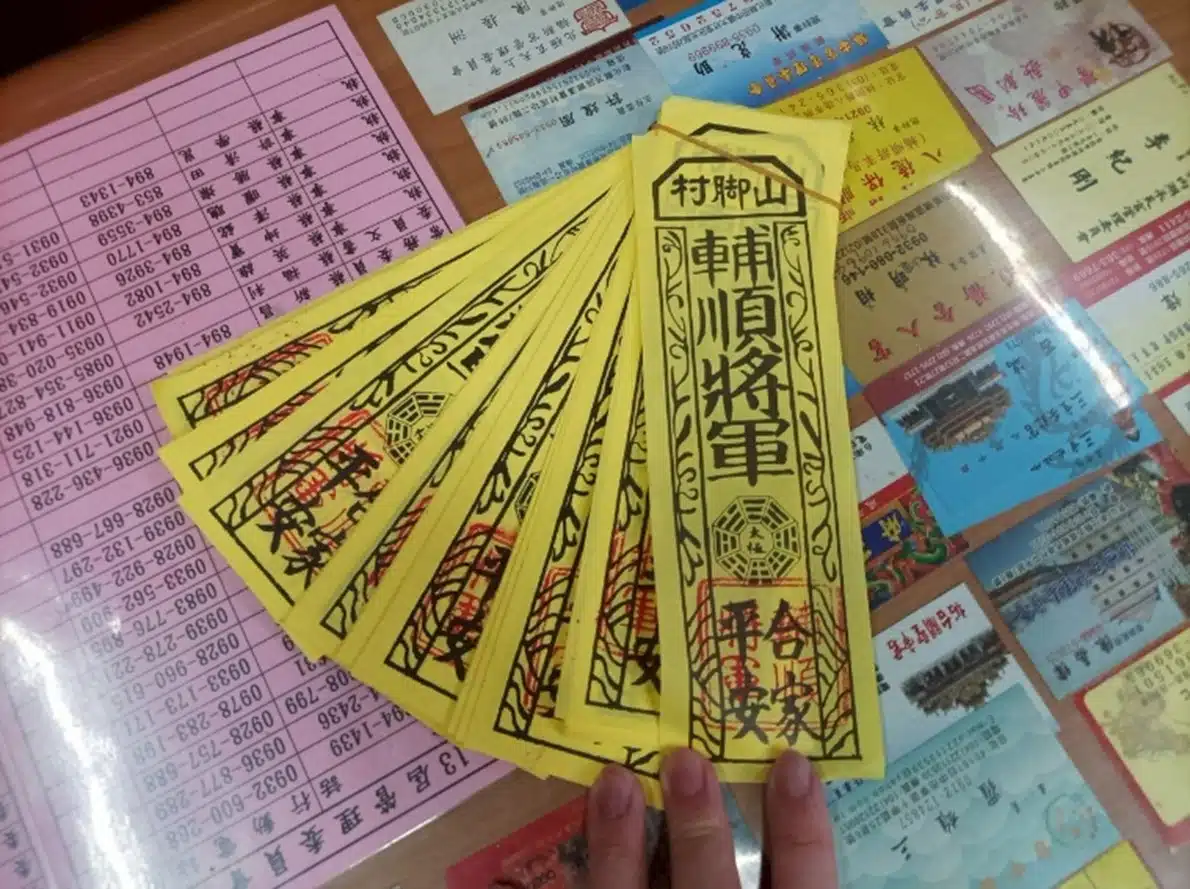

Elvira’s authority was never the result of a formal appointment, but instead emerged gradually through her daily presence within the temple. Living near the temple, she rises at 5:30 a.m. to open the gates, light incense, clean, and prepare offerings. On days when there is a ceremony or ritual to perform, she comes still earlier. With deliberate care, she folds talismans into Wan’an Temple’s distinctive star-shaped amulets, believed to carry General Fushun’s blessing. She remains until late evening, closing the gates after the last visitors have departed.

Elvira also oversees rituals such as an tai sui (安太歲), performed when someone’s zodiac year is in conflict with Tai-sui, a rotating celestial deity. In Taiwan, people are classified according to the year they were born into with one of the twelve animal signs, also known as the Chinese Zodiac. Tai-sui changes His location every year, with the location linking to one zodiac. When the deity shifts into the position of a particular sign, those born under that sign are thought to fall under its shadow of misfortune, a condition called fan tai sui (犯太歲, meaning to offend Tai-sui). Believers perform the an tai sui ritual to ward this off, worshipping Tai-sui, praying for peace, and lighting lanterns to dispel disasters and resolve misfortunes.

Elvira plays an important role in helping believers draw lots, or pua̍h pue (擲筊). In drawing lots, believers communicate with deities or ancestors by throwing a pair of crescent-shaped wooden blocks. The approval of deities or ancestors is signaled by siūnn pue (聖筊), wherein one wooden block lands flat side up and the other rounded side up, and Elvira will assist believers in explaining the meaning of the lots poem (籤詩) and help them seek guidance. During General Fushun’s annual birthday festival—starting on the 14th of September based on the lunar calendar, typically sometime in October according to the Gregorian calendar—Elvira leads preparations several weeks in advance for the biggest event of the year, which draws devotees from across Taiwan.

Wan’an Temple is more than a religious site; it is Dacheng’s social center. Villagers gather in the square after farm work to chat, share homegrown vegetables, and drink tea. Elvira joins them, becoming part of the neighborhood’s daily fabric. Life in a rural township has its inconveniences, but Elvira describes it as peaceful and welcoming, a slower pace she has come to cherish as she adapts to the social rhythms of rural Taiwanese life.

Distance from her family in Chile has been harder. For decades, she could only exchange letters that took months to arrive. In 2016, with help from villagers’ donations, she finally returned to visit her family. After more than three decades in Taiwan, she recalled that she sometimes slipped Taiwanese or Mandarin words into conversations with her relatives, an unintentional sign of how deeply she had integrated.

Elvira’s story shows that belonging is not always a matter of bloodline or formal recognition, but something woven through daily practice, shared participation and trust. The villagers of Dacheng did not dwell on her foreign origins or question her religious credentials; they saw someone who showed up every morning, opened the gates, tended the incense and performed the rituals when needed. Her identity, layered between Catholic roots and Taiwanese folk traditions, reflects a flexible approach to faith shaped by circumstance, devotion and long-term experience rather than adherence to a doctrinal body of text. In a society where temple leadership is typically male, local, and hereditary, Elvira has quietly redrawn the boundaries of whom can serve as a legitimate religious figure. Above all, she sees no contradiction in the life she has embraced at Wan’an Temple. As she put it herself, “I am a Taiwanese.”

References

Chang, Jia-lin. 2009. “Soul-Calling, Exorcism, and Blessing: An Analysis of the Factors Behind Why Worshippers Seek Siu-kiann at Xingtian Temple.” Tamsui Oxford Journal of Art, 7: 198–225.

Chen, Chun-chin. 2014. “Educed from Dunhuang Lunisolar Calendar: A Study on the Development of Tai-sui Gods.” Journal of the Chinese Department, National Chung Hsing University, 36: 61–102.

Yo, Mei-hui, 2024. “Just cooking? Exploring Experiences of Senior Women as Temple Volunteers.” Doctoral thesis of Ph.D. Degree Program in Gender Education, National Kaohsiung Normal University.

One Little Day (小日子), 2023. “Love makes people impulsive and reckless, but also gentle and strong” [愛讓人衝動莽撞 也讓人溫柔堅強], One Little Day, https://onelittleday.com.tw/124090-6/.

Liu Yen-Tang is a Master Student in Ethnology at the National Chengchi University, Taiwan