Very few studies have been conducted about the Murshidiyya and the fieldwork done by Dmitry Sevruk in 2010 remains the most up-to-date study of this community. Dmitry Sevruk has a PhD in Islamic Studies from the University of Bamberg. His doctoral thesis, entitled Die Muršidiyya: Entstehung und innere Entwicklung einer religiösen Sondergemeinschaft in Syrien von den 1920er Jahren bis heute (University of Bamberg Press, 2013) is the most up-to-date study of this religious community. He is currently Head of Oriental Studies Department, at the National Academy of Sciences in Minsk, Belarus.

Religioscope – An ethnoreligious group, a new religious movement, a tribal faith? How can we define the Murshidiyya?

Dmitry Sevruk – Imam Sājī, who was the last official head of the community, defined the Murshidiyya as a religion (al-murshidiyya dīn). And there is no reason to dispute his words. Of course, there are some elements of what can be called ethnoconfessionalism: the community traces back its fictive genealogy to the pre-Islamic Ghassanide tribe, and the purpose behind this historical mythology is undoubtedly to emphasize a pure Arab origin of community members. Retrospective presentation of the Murshids as “pure Arabs” is especially important for the period up to the mid-1960s, as many of the Syrian elites of that time, as well as noble families, still had an Ottoman cultural background. Nevertheless, this Murshidi combination of religious and ethnic identity is not yet comparable to that of the Yezidis or Israeli Druze, that’s why I prefer the definition “religious community” or “religious group”. A “new religious movement” is also possible.

What are their demographic make-up and geographical distribution?

DS – This is probably one of the most difficult questions. I know that Murshidites can be found among representatives of different strata of Syrian society. As for exact statistics, I don’t think they exist. During my field research in 2010, I heard widely different information about the number of community members. In a conversation with me, Dr. Āṣif aṣ-Ṣāliḥ, one of the Murshidi religious authorities, spoke about 450-500,000 Murshidis. Nur al-Muḍī’ considered this number exaggerated. Muḥammad al-Arnā’ūṭ, a historian from Jordan, wrote in one of his articles about 300,000 Murshidis. In all three cases, the assessment seemed rather intuitive. I doubt that there are any trustworthy statistics, especially now, when sectarian affiliation in Syria has a political dimension more than ever.

We have the same problem with the geographical distribution of the community. I tried to compose a detailed map of Murshidi villages and settlements but due to a number of reasons it turned out to be impossible. General description of the communal geography can be found in the work “Lamaḥāt ḥawla al-murshidiyya” (Views on the Murshidiyya, 2007) composed by Nur al-Muḍī’. I refer to it in my article “Murshidis of Syria”: Nūr al-Muḍī’ reports about two branches of the tribe (or of the community) which have existed already by the end of the 1940s: al-Qabālā (the Southerners) and ash-Shamālā (the Northerners). This division exists till today: to ash-Shamālā belong the members of the community around Latakia and in the region of al-Ghāb, al-Qabālā are the Murshidis of Homs, the region of Masyaf, the suburbs of Damascus and (until 1967) the villages of the Golan Heights (like Za’ūrā or al-Ghajar).[1] The inhabitants of Jawbat Burghāl, Salmān Murshid’s native village, do not belong to the community today.

There is also no doubt that after the outbreak of the war in Syria in 2011, a significant number of Murshidis migrated both to other Arab countries and to Western Europe. You will sure find many of them in Germany, for example.

What are the main historical milestones of that religious community since its founding in 1926?

DS – In my dissertation, I divide the history of the Murshidiyya into four periods:

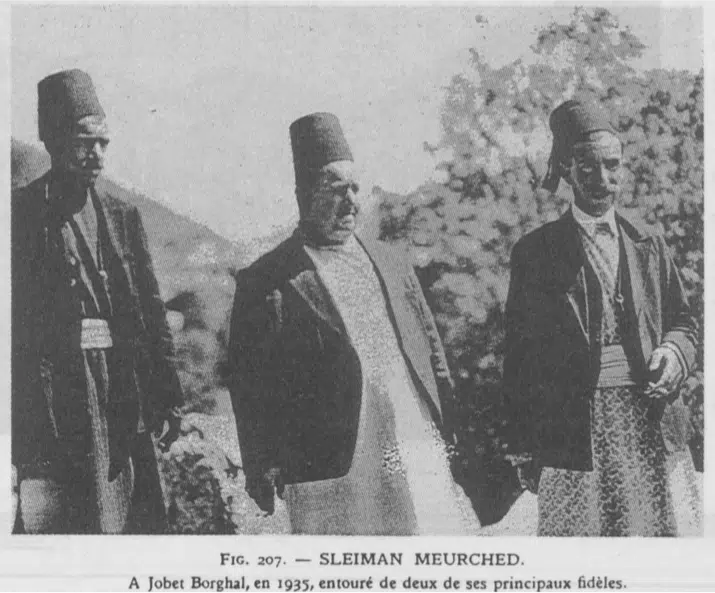

1923-1946 – the period of Salmān Murshid and the emergence of the tribe al-Ghasāsina (the Ghassanides). By the way, sometimes he is called Suleyman, but it seems to be a result of a mistake occurred due to the similarity of the two names, especially in pronunciation. In official papers (parliamentary minutes, trial documents) he is mentioned as Salmān.

1946-1952 – the leadership of Mujīb al-Murshid, the most mysterious period in the history of the Murshidiyya. There are almost no reliable sources about it.

1952-1998 – the Imamate of Sājī al-Murshid and the final transformation of the tribe al-Ghasāsina into a separate religious group.

1998-2015 – the time of Nūr al-Muḍī’ al-Murshid, the fourth son of Salmān and his first wife Hilāla. Nūr al-Muḍī’ wasn’t an official leader, but I have no doubts that he was informally considered the highest authority in religious and political matters.

Now, I would say that the year 2015 (after the death of Nūr al-Muḍī’ (1944-2015) is the beginning of a new period that has yet to be studied.

Salmān al-Murshid is believed to have manifested supernatural powers and later on recognized as the reincarnation of a celestial being by the local Alawite community, progressively becoming a religious leader. Beyond the hagiographies, what do we actually know about al-Murshid?

DS – There are enough reports on Salmān Murshid and they come from completely different sources: from openly anti-Murshidi propaganda written by Jūrj Dakar to the hagiographic book composed by Nūr al-Muḍīʾ. Very important are reports of French and British intelligence officers as well as documents from Murshid’s trial, published by Ahmad Issa al-Fil. Despite the diversity and some inconsistency of the sources, we can quite fully restore the biography of Salmān, and even hagiographies can help us in this case. Most sources indicate 1907 as the year of his birth. However, there is one British Foreign Office document, which states that Murshid was born around 1895. It was unknown to me at the time of my dissertation, and if we assume that the year in the British document is correct, we can easily explain the organizational abilities of the young leader. He was not as young as was commonly believed. By the way, even on the photos, he looks much older than if he had been born in 1907. Almost all sources give 1923 as the year when Salmān, who apparently was born in a poor lay family, began to receive revelations. Jūrj Dakar and British intelligence officer Richard Belgrave report that this was the result of a serious illness. It is very likely that the consolidation around Salmān was initiated by some Alawi religious authorities. For today’s Murshidites, 1923 is also the year of “the reunion of the Ghassanide tribe”. In fact, the merger of some Alawi clans into a new tribal union most likely took place later, when Salmān was no longer a symbolic, but a real political leader. The support of some religious authorities and marriage to the daughter of one of them made him a significant figure not only in the political and social but also in the religious life of his supporters. It was believed that his firstborn would be the expected Messiah. One interesting circumstance should be mentioned here: Salmān had many wives, but the key role in the life of the community was played exclusively by his sons from his first wife Hilāla, the daughter of an influential religious Alawi sheikh.

Salmān al-Murshid was an extraordinary talented politician. His detailed biography is still waiting for its author. Now, it’s enough to say that several times he was elected to the Representative Council of the Alawite State. After 1936 he was a member of the Syrian parliament. He skilfully balanced between the French and Syrian nationalists. Salmān Murshid controlled not only a number of Alawi tribes, but also made an alliance with local Bedouins. He had his own guard and controlled the trade of tobacco – the main source of income for Alawi peasants. In short, Salmān Murshid became in the mid-1930s the most influential Alawi chief, who practically had his own state within the state. Some authors also mention the tricks with which he maintained faith in his supernatural abilities. After the final withdrawal of the French in 1946 and with the beginning of power centralization in Damascus, such a figure seemed to be dangerous for the new political elites of independent Syria. As a result of a military operation, Murshid was arrested and after a trial executed in Marge Square in Damascus in 1946. This is now a very short overview. A more detailed conversation about this man would take many hours and many pages. Anyway, the central figure of the Murshidi religious cult is not Salmān but his second son Mujīb.

Who is/are today the main leaders of the community? Was Imam Saji the last person who could speak on behalf of all Murshidis?

DS – Indeed Imam Sājī was the last person who could speak officially on behalf of all Murshidis. Nevertheless, Nūr al-Muḍī’, whom I interviewed in the village Qatra in 2010, was a very influential person. I would say that he was an unofficial leader of the community with no less power than his elder brother Sājī. The situation with leadership after his death in 2015 is not very clear. To understand it, field research is needed, but it is quite difficult to organize it in the current circumstances. In the 1980s, Sājī Murshid organized the so-called “School of Imam Saji” (madrasat al-imām Sājī), where the disciples chosen by him learned from him the basics of the Murshidi religious doctrines. For example, Dr. Āṣif aṣ-Ṣāliḥ who helped me during my field research in Syria was one of them. I don’t think that the Murshidis have one main leader today, but I guess that the disciples of Imam Sājī like Dr. aṣ-Ṣāliḥ have a certain authority and influence in the community.

Salman al-Murshid announced the unification of Bani Ghasan’s three clans of al-Amamira, al-Mahaliba and al-Darwisa on July 12, 1923 (Ittihad al-Sha’ab al-Ghasani al-Haidri). That day is still celebrated today by the community. Would you agree with the statement that al-Murshid created a new Asabiyyah (group consciousness) articulated around a new faith, more than he created a “religious movement”?

DS – First of all, it should be noted that we do not know exactly when the three Alawi clans united into a new tribe or tribal confederation. The date July 12, 1923, is mentioned in the book of Nūr al-Muḍī’ and most likely became a part of the official Murshidi history relatively late. Salmān Murshid created neither a new religious movement nor a new faith. He was supported by several religious sheikhs and apparently identified himself as Alawi. A distinctive feature of him and his followers were their emphasized messianic expectations. But this fits perfectly into the paradigm of Alawi religious ideas, which even today are not something homogeneous. Perhaps that is why he also created a new tribal union, which in fact was not a religious, but a political entity. His conflicts with other Alawite leaders were not of religious but of political and economic nature. I would say that the transformations undertaken by Salmān (messianic element, a new tribal structure) have become the starting point for the formation of a new group consciousness developed later by his sons.

What do we know about Murshidi religious beliefs, rituals and celebrations?

DS – I wouldn’t say that in the case of the Murshidiyya we can speak about a developed and structured theology. Nevertheless, the main elements of their beliefs are quite simple to identify. First of all, the Murshidis consider their community a branch (far’) within Islam. At the same time, they adhere to a very broad interpretation of the word “Islam” by referring to the 19th verse of the surah “Al Imran”: “Truly, the religion with God is Islam”. According to this logic, every religion that declares the obedience to God is Islam. Even Christianity or Judaism. This, by the way, is a little bit similar to the ideas of Antun Saadeh (1904-1949), a pan-Syrian nationalist, who wrote about the Christian and Muslim messages of Islam.

Very important for the Murshidis is the belief in metempsychosis (tikrār al-qumṣān). This idea is closely connected with the Murshidi religious anthropology that is in fact inherited from ancient Gnostic doctrines and divides a person into body (jasad), soul (nafs) and spirit (rūḥ). Only spirit (rūḥ) is considered a part of Divine Essence, which shall return to the world of spirits (‘ālam al-arwāḥ). Return is possible through a righteous life and the rebirth in a new body gives to the spirit a new opportunity to get rid of the physical shell, if it did not succeed in this in a previous life. These ideas also determined the special attitude of the Murshidis to death, which is considered a release of the spirit and is not a reason for a mourning. Typical Murshidi words of condolence are “Aḥsana Allāh ikhlāṣa-hu” (May Allah make good his salvation or his release).

Very important is also the idea of free will. According to the Murshidi beliefs, every person bears complete responsibility for his own deeds that are results of his own will. That is why a significant part of Sājī’s commandments are ethical prescriptions.

The ritual life of the Murshidis is very simple. I was informed that they have only two daily prayers (at the time of sunrise and sunset), which aren’t obligatory. I do not possess the texts of these prayers, but I am sure that they go back to Imam Sājī.

The only Murshidi religious festival is “’Īd al-faraḥ bi-Llāh”. It can be roughly translated as “the Feast of joy in God”. The festival is celebrated every year from 25 to 27 August. According to the beliefs of the present-day Murshidis, on the August 25th, Mujīb al-Murshid who is revered as a promised Messiah (al-qā’im al-maw’ūd) proclaimed the beginning of a “new religious message” (ad-da’wa al-jadīda), a new period in human history.

In addition to this festival, the Murshids have so-called “occasions” (munāsabāt) that are not considered religious holidays, but are occasions for celebrations. The most important of them is probably the Reunion of the Gassanide people (ittiḥād ash-sha’b al-ghassānī) on July 12. Another one is the October 5th. On this day in 1951 Mujīb Murshid was released from the prison. On May 5, every Murshidi can organize a night celebration, symbolizing his gratitude to God.

It should be emphasized that we are talking about modern religious doctrines and rituals. In the previous stages of the Murshidi history, especially before the 1970s, beliefs and rituals were different.

How does it differ from the Alawi faith?

DS – There are two fundamental differences between the two groups. Unlike the Alawis, the Murshidis do not have a complex religious hierarchy. In their opinion, the Alawi veneration of religious sheikhs can be compared with idolatry (ṣanamiyya). They believe that each person is able to comprehend religious doctrines on his own. This is very similar to the Protestant approach. In the Murshidite community, you will find only an “instructor” (mulaqqin) who teaches boys and girls prayers. Another fundamental difference is that the Murshidites do not have a complex esoteric theology, accessible only to initiates.

What are the different influences (Shia Islam, Zoroastrianism, Christianism, etc.) that have shaped the Murshidi faith?

In most general terms, the Murshidiyya can be described as the reformed Alawi faith, which Heinz Halm considers a branch of Shia ghulat that have survived to our days. This explains Gnostic anthropology and soteriology, veneration of Ali and other imams, as well as a special meaning of the word “imam” in the Murshidiyya. There are also some similarities with Christian terminology: one of Mujīb Murshid’s epithets is “Savior” (mukhalliṣ). The same word is used by Arab Christians for Jesus. Some metaphors in Sājī’s poems (first of all, wine as the symbol of the Divine knowledge) refer to Sufi poetry. But even these elements could be inherited from the Alawis. Some ancient Iranian festivals that are mentioned in religious texts of the Alawis (nawruz, mihrajan) are not celebrated by the Murshidis and there is no reason to speak about Iranian or Zoroastrian influences on them.

Are there any written sources that the community regard as key to their belief? Is Muhawarath awla al-Murshidiyya (Dialogues about the Murshidiyya), compiled by Nur al-Mudi al-Murshid (c. 2003–2009), the main source for the transmission of their beliefs?

There are two main written sources that the community regards as a key to their doctrines: “Lamaḥāt ḥawla al-Murshidiyya” and “Muḥāwarāt ḥawla al-Murshidiyya”. Both texts were written by Nūr al-Muḍī’. Apparently, his aim was to fix, standardize and systematize the main elements of the religion for future generations. Another task was surely to construct the communal historical memory: “Lamaḥāt ḥawla al-Murshidiyya” is nothing but a hagiographic description of the history of the community. Some texts ascribed to Mujīb or Sājī aren’t published yet, but they are known among the Murshidis. It is possible that some kind of oral tradition also exists.

Do the Murshidis try to attract new followers or is it mainly a tribal or ethnic identity?

The Murshidiyya is not a tribal or ethnic identity. At least, officially. Theoretically, anyone can become a Murshidi, but practically it seems to be quite difficult in a state where sectarian divisions are very strong and have a political dimension. Moreover, today’s Murshidis do not attempt to attract new followers: they believe that accepting the faith should be an act of free will. That is why they officially reject missionary work.

Have the Murshidis attempted to be officially recognized by the State or any other religious authority, in the same manner that the Alawites did in 1973 via a fatwa declared by the Lebanese Shia cleric Musa Sadr?

I don’t know anything about such attempts. I don’t think they took place.

How are the Murshidiyya treated by a government whose levers of power are all in the hands of Alawites?

After Hafez al-Assad came to power, the Murshidis were integrated into the state. It would be more correct to say that the community, which had been oppressed before, was instrumentalized by the new government. As a result of close contact with Rifaat al-Assad, Nūr al-Muḍī’ became a major contractor. Community members formed the backbone of “Sarāyā ad-difā’”, the Praetorian Guard of Assad brothers. During the conflict between Hafez and Rifaat, the Murshidis supported Hafez and since then many of them have remained loyal to the clan, which opened for them the opportunity to become а part of Syrian economic and military elite. Of course, this does not mean that absolutely all Murshidis support the current Syrian regime, but the percentage of supporters should be high.

Note

- D. Servuk, “The Murshidis of Syria: A Short Overview of their History and Beliefs”, The Muslim World 103, no. 1 (2013): 93. ↑

The colourised version of the 1944 photograph of Salman Al-Murshid on the homepage was created using the online tool Palette.fm.