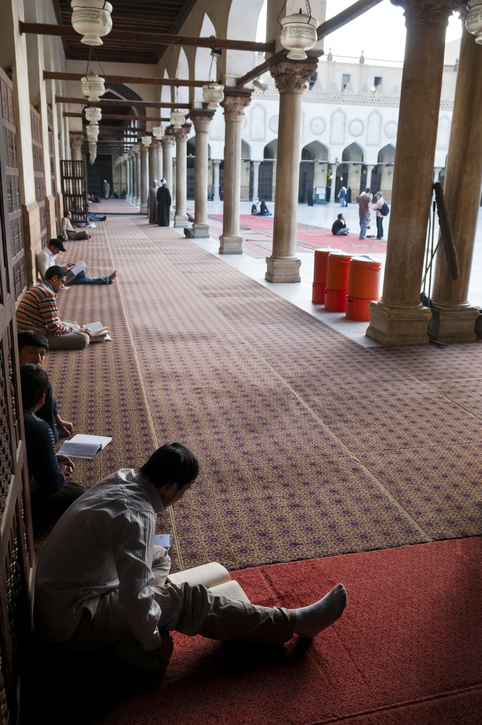

When Pope Francis I visited Egypt in 2017 to stimulate inter-faith dialogue he walked into a religious and geopolitical minefield at the heart of which was Al-Azhar, one of the world’s oldest and foremost seats of Islamic learning. The pope’s visit took on added significance with Al-Azhar standing accused of promoting the kind of ultra-conservative Sunni Muslim Islam that potentially creates an environment conducive to breeding extremism.

The pope’s visit came as Al-Azhar, long a preserve of Egyptian government and ultra-conservative Saudi religious influence, had become a battleground for broader regional struggles to harness Islam in support of autocracy.

At the same time, Al-Azhar was struggling to compete with institutions of Islamic learning in Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Jordan as well at prestigious Western universities.

The battleground’s lay of the land has changed in recent years with the United Arab Emirates as a new entrant, a sharper Saudi focus on the kind of ultra-conservatism it seeks to promote, and Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s efforts since 2015 to impose control and force Al-Azhar to revise its allegedly conservative and antiquated curriculum that critics charge informs extremism.

Ordained by God

Addressing a peace conference at Al-Azhar, the pope urged his audience to “say once more a firm and clear ‘No!’ to every form of violence, vengeance and hatred carried out in the name of religion or in the name of God.”

In doing so, the pope was shining a spotlight on multiple complex battles for the soul of Islam as well as the survival of autocracy in the Middle East and North Africa. These battles include Saudi efforts to distance ultra-conservatism from its more militant, jihadist offshoots; resistance to reform by ultra-conservatives who no longer are dependent on support of the kingdom; and differences between Saudi Arabia and some of its closest Arab allies, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, in their approaches towards ultra-conservatism and opposition to extremism.

Mr. Al-Sisi, referring to assertions that Al-Azhar’s curriculum creates a potential breeding ground for extremism, charged at the outset of his campaign that “it is impossible that this kind of thinking drive the entire world to become a source of anxiety, danger, killing and destruction to the extent that we antagonize the whole world. It’s unconceivable that 1.5 billion Muslims will kill the whole 7 billion in the world so that they alone can rule.”

Mr. Al-Sisi, often prone to hyperbole and self-aggrandisement, threatened the university’s scholars in 2015 that he would complain to God if they failed to act on his demand for reform. “Allah Almighty be witness to your truth on Judgment Day concerning that which I’m talking about now.,” Mr. Al-Sisi said.

Speaking months later to a German Egyptian community, Mr. Al-Sisi, an observant Muslim who in a 2006 paper argued that democracy cannot be understood without a grasp of the concept of the caliphate, asserted that “God made me a doctor to diagnose the problem, he made me like this so I could see and understand the true state of affairs. It’s a blessing from God.”

Mr. Al-Sisi’s assault on Al-Azhar was sparked by multiple factors: the Islamic State’s extreme violence; pressure by the United Arab Emirates that more recently joined the fray of those seeking to shape Islam in their mould, and the experiences of Egyptian intelligence officers with militants.

“Hatred and bloodshed are backed up by curricula…that are approved by Islamic scholars, the ones that wear turbans… When I interrogated the extremists and talked to the Azhari scholars, I reached the conclusion that extremism comes primarily from the ancient books of Islamic jurisprudence which we’ve turned into sacred texts. These texts could have been forgotten long ago had it not been for those wearing the turbans,” said former Egyptian intelligence officer and lawyer Ahmad Abdou Maher, a strident critic of Al-Azhar.

Islam al-Bahiri, another Al-Azhar critic, who was jailed for his views and later pardoned by Mr. Al-Sisi charged that “Al-Azhar is part of the problem, not the solution. It cannot reform itself because if it does reform itself it would lose all authority. Al-Azhar is fighting for its own survival and not for the religion itself… They want you to follow religion as they understand it.”

Ironically, Mr. Al-Sisi has himself to blame for Al-Azhar’s ability to fend off the president’s effort. In attempting to not only tighten state control of Al-Azhar, Mr. Al-Sisi overreached by trying to fundamentally alter its power structure.

Legislation introduced in parliament would have limited the tenure of the grand imam, create a committee that could investigate the imam if he were accused of misconduct, broadened the base that elects the imam, included laymen in the Body of Senior Scholars that supervises Al-Azhar, and added presidential appointees to the Supreme Council of Al-Azhar.

Mr. Al-Sisi’s overreach enabled Al-Azhar, in a rare example of successful opposition to his policies, to mobilize its supporters in and outside of parliament and defeat the legislation. It also allowed Al-Azhar to reject out of hand of Mr. Al-Sisi’s demand that it rewrites the rules governing divorce to make it more difficult for husbands to walk away.

The proposed legislation nonetheless sent a message that was heard loud and clear in Al-Azhar. In response to Mr. Al-Sisi’s assault, the leadership of Al-Azhar has sought to curb anti-pluralistic and intolerant statements by some members the faculty, set up an online monitoring centre to track militant statements on social media, and paid lip service to the need to alter religious discourse. It has, however, stopped short of developing a roadmap for reform of the institution and its curriculum.

Differences of opinion between ultra-conservatives among the Al-Azhar faculty and those more willing to accommodate demands for reform surface regularly.

Soaad Saleh, an Islamic law scholar and former head of Al-Azhar’s fatwa committee, last year publicly criticized a ruling by grand mufti Shawki Allam that exempted Egypt’s national team from fasting during Ramadan in the run-up to the 2018 World Cup.

Ms. Saleh argued that only those travelling for reasons that please God such as earning money to feed the family, study or to spread the word of God were exempted from fasting. Soccer did not fall in that category, the scholar said.

Ms. Saleh earlier asserted that Muslims who conquered non-Muslims were entitled to sex slaves. “If we [Egyptians] fought Israel and won, we have the right to enslave and enjoy sexually the Israeli women that we would capture in the war,” Ms. Saleh said.

Ms. Saleh remains a member of the Al-Azhar faculty. So is Masmooa Abo Taleb, a former dean of men’s Islamic studies who argued several years ago that Al-Azhar had endorsed the principle that Muslims who intentionally miss Friday prayer could be killed.

Combatting extremism

Al-Azhar nevertheless asserts that it has reviewed its curriculum and was working with the education ministry to revise school textbooks. It rejects suggestions that the revisions are primarily cosmetic.

“We have done a number of corrective as well as preventive measures to respond to this urgent call about reforming Islamic religious discourse. We have revisited a number of religious fatwas that were authored in the past; fatwas that unfortunately have given rise to a number of wrong behaviours,” said Ibrahim al-Najm, a senior scholar at Dar al-Iftar, the Al-Azhar unit responsible for legal interpretations.

Mr. Al Najm pointed to a revision of a fatwa that authorized female genital mutilation as well as Al-Azhar Facebook pages with millions of followers that refute jihadist teaching such as those of the Islamic State. A recent online textbook says in the introduction: “We present this scientific content to our sons and daughters and ask God that he bless them with tolerance and moderate thought … and for them to show the right picture of Islam to people.”

Yet, scholars of the university struggle when confronted with an Al-Azhar secondary school textbook, a 2016 reprint of a book first written hundreds of years ago that employs the same arguments used by jihadists. The book defines jihad exclusively as an armed struggle rather than the struggle to improve oneself and contains a disputed saying of the Prophet according to which God had commanded Mohammed to fight the whole world until all have converted to Islam.

Scholars argued that such texts were part of history lessons that teach Islamic law, including the rules of engagement in war in times past. They assert that students are taught that interpretations of the law in historic texts may have been valid when the books were written but are not applicable to the modern-day world.

They further stress that the concept of jihad an-nafs, the struggle for improvement of oneself, was taught extensively in classes on ethics and morals. Al-Azhar has nonetheless advised faculty that they should not allow students to read old texts without supervision. Panels have been created to review books to ensure that they do not advocate extremist positions.

Al-Azhar’s critics charge that it is plagued by the same literalism and puritanical adherence to historic texts that radicals thrive on and that feeds intolerance and discrimination. Al-Azhar has lent credibility to those charges through various positions that it adopted. Those include, for example, demanding closing down a TV show that advocated the purge of canonical texts that promote violence against and hatred of non-Muslims and the suspension of a professor for promoting atheism by using books authored by liberals.

Al-Azhar’s huge library that provides teaching materials is a target too. It contains volumes of interpretations of the Qur’an and the sayings of the prophet written over the centuries, some of which preach militant attitudes such as a ban on Muslims congratulating Christians on their holidays, a Muslim’s duty to fight infidels, the imposition of the death penalty on those who abandon Islam, and harsh punishments for homosexuals.

The blurring of the lines

Complicating the effort to reform Islam is a dichotomy shared by both Al-Azhar and Mr. Al-Sisi. Both accept the notion of a nation state and see themselves as guardians of Islamic Orthodoxy, witness the crackdowns for example on LGBT, as well as Mr. Al-Sisi’s failure to make good on his promise to counter discrimination of Egypt’s Coptic minority and widespread bigotry among the Muslim majority.

Al-Azhar and Mr. Al-Sisi also both embrace the civilizational concept of the ummah, the community of the faithful that knows no borders. Their efforts to counter extremism are moreover not fundamentally rooted in values that embrace tolerance and pluralism despite the adoption of the lingo but as defenders of Muslim conservatism against extremism and jihadism, trends they deem to be heretical.

In a study written in 2006 at the US War College, Mr. Al-Sisi, a deeply religious man whose wife and daughter are veiled, pushed the notion that democracy in the Middle East needed to be informed by the ‘concept of El Kalafa,’ the earliest period of Islam that was guided by the Prophet Muhammad and the Four Righteous Caliphs who succeeded him. “The Kalafa, involving obedience to a ruler who consults his subjects, needed to be the goal of any government in the Middle East and North Africa,” Mr. Al-Sisi wrote.

Resistance within Al-Azhar to Mr. Al-Sisi’s calls for fundamental reform is nonetheless deeply engrained. It has been boosted by a history of fending off attempts to undermine its independence, a deeply embedded animosity towards government interference and its definition of itself as the protector of Islamic tradition.

It has also been undergirded by decades of Saudi influence that was long abetted by Mr. Al-Sisi’s predecessor, Hosni Mubarak, and Mr. Al-Sisi’s high-handed approach.

The resistance within Al-Azhar to Mr. Al-Sisi’s campaign is further informed by the fact that although still revered, Al-Azhar no longer holds a near monopoly on Islamic learning. Beyond the competition from Saudi, Jordanian and Turkish institutions, Al-Azhar is also challenged by Islamic studies at European and North American institutes such as Leiden University, Oxford University, London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) the University of Chicago and McGill University.

Yet, those institutions too are not immune to producing ultra-conservatives. Take for example, Farhat Naseem Hashmi, a charismatic, 60-year old Pakistani Islamic scholar and cultural entrepreneur who graduated from the University of Glasgow. Ms. Hashmi has become a powerful ultra-conservative force among Pakistan’s upper middle class. Or Malaysian students in the Egypt, UK and elsewhere who were introduced to political Islam by Muslim Brotherhood activists at their universities.

Muhammed Azam of the Kuala Lumpur-based International Institute of Islamic Studies notes that the Malaysian government no longer funds students that want to go to Al-Azhar. “If they go (to Al-Azhar), it is self-funded,” Mr. Azam said. He noted further that Saudi Arabia had stepped in to offer hundreds of scholarships at institutions in the kingdom. “Because of the financial constraints, people to go to whatever country has got sponsorship,” Mr. Azzam said.

At the same time, Mr. Azzam said more Malaysians were heading to Jordan. “There is a shift. Malay parents now send their kids to Jordan to further their studies either in Islamic studies or Sharia or one specific subject matter or banking and finance… They have a different curriculum. They have the Islamic and the secular curriculum and that has given a different result for the graduates who come back,” he said.

A grinding, long drawn out battle

The upshot of all of this is that the struggle for Al-Azhar is likely to be grinding and drawn out rather than swift and decisive. It is a political, geopolitical and religious battle in which Mr. Al-Sisi, backed by his Gulf allies, sees religious reform as one key to countering perceived security threats and extremism.

His nemesis, a Sorbonne-educated imam of the Al-Azhar Grand Mosque, Ahmed El- Tayeb, pays lip service to the notion of reform but insists that textual fidelity is a sign of piety, expertise and righteousness, not obscurantism. Reform in Mr. El-Tayeb’s view cannot entail abandoning unambiguous Koranic texts or authentic sayings of the Prophet or hadiths.

Mr. Al-Sisi appears to also have learnt a lesson from his failed effort to bend Al-Azhar to his will. His religious endowments ministry has laid the groundwork for male and female imams to be trained at a newly-inaugurated International Awqaf Academy, which is attached to the presidency, rather than Al-Azhar. The ministry has drafted the curriculum to include not only religious subjects but also politics, psychology and sociology.

Built on an area of 11,000 square meters, the academy boasts a high-tech infrastructure with foreign language and computer labs. Sheikh Abdul Latif al-Sheikh, the Saudi Islamic affairs minister, attended the inauguration and promised that the Saudi Institute of Imams and Preachers would work closely with the academy. Select Al-Azhar faculty have been invited to teach at the academy. Training courses last six months.

The academy competes with the just opened Al-Azhar International Academy that in contrast to the government’s academy focuses exclusively on religious subjects. The Al-Azhar initiative builds on the institution’s international outreach in recent years that was designed to combat extremism and project Al-Azhar as independent and separate from the Egyptian government.

Parallel to the inauguration of the government academy, Mr. Al-Sisi, in an effort to curtail Al-Azhar’s activity decreed that senior officials including Mr. El-Tayeb would need to seek prior approval from the president or the prime minister before travelling abroad.

As part of his effort to micro-manage every aspect of Egyptian life and frustrated at Al-Azhar’s refusal to bow to his demands, Mr. Al-Sisi, moreover, ignoring Al-Azhar objections, instructed his religious affairs ministry to write standardized sermons for all mosque preachers.

While resisting Mr. Al-Sisi’s attempts to interfere in what Al-Azhar sees as its independence and theological prerogatives, it has been careful not to challenge the state’s authority on non-religious issues. This was evident in Al-Azhar’s acquiescence in the arrest in 2015 of some 100 Uyghurs, many of them students at Al-Azhar, who at China’s request were deported to the People’s Republic.

Convoluted geopolitics

The pope’s interlocutors at Al-Azhar meanwhile tell the story of the institution’s convoluted geopolitics.

They included former Egyptian grand mufti Ali Gomaa, an advocate of a Saudi-propagated depoliticized form of Islam that pledges absolute obedience to the ruler, an opponent of popular sovereignty, and a symbol of the tension involved in adhering to both Saudi-inspired ultra-conservatism that serves the interests of the Saudi state, and being loyal to the government of his own country.

A prominent backer of Mr. Al-Sisi’s grab for power, Mr. Gomaa frequently espouses views that reflect traditional Saudi-inspired ultra-conservatism rather than the form projected by crown prince Mohammed bin Salman.

In an interview with MBC, a Saudi-owned media conglomerate, Mr. Gomaa asserted in 2015 that women did not have the strength to become heart surgeons, serve in the military, or engage in sports likes soccer, body building, wrestling and weightlifting. A year later, Mr. Gomaa issued a fatwa declaring writer Sherif El-Shobashy an infidel for urging others to respect a woman’s choice on whether or not to wear the veil.

Prince Mohammed has since 2015 significantly enhanced women’s professional and sporting opportunities although he has not specifically spoken about the sectors and disciplines Mr. Gomaa singled out.

Pope Francis’ interlocutors in Cairo also included Mr. El-Tayeb, the imam of the Grand Mosque. A prominent Islamic legal scholar, who opposes ultra-conservatism and rejected a nomination for Saudi Arabia’s prestigious King Faisal International Prize, recalls Mr. El-Tayeb effusively thanking the kingdom during panels in recent years for its numerous donations to Al-Azhar. Al-Azhar scholars, the legal scholar said, compete “frantically” for sabbaticals in the kingdom that could last anywhere from one to 20 years, paid substantially better, and raised a scholar’s status.

“Many of my friends and family praise Abdul Wahab in their writing,” the scholar said referring to Mohammed ibn Abdul Wahhab, the 18th century religious leader whose puritan interpretation of Islam became the basis for the power sharing agreement between the kingdom’s ruling Al Saud family and its religious establishment. “They shrug their shoulders when I ask them privately if they are serious… When I asked El-Tayeb why Al-Azhar was not seeing changes and avoidance of dogma, he said: ‘my hands are tied.’

To illustrate Saudi inroads, the scholar recalled being present when several years ago Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy, a former grand mufti and predecessor of Mr. El-Tayeb as imam of the Al-Azhar mosque, was interviewed about Saudi funding. “What’s wrong with that?” the scholar recalls Mr. Tantawy as saying. Irritated by the question, he pulled a check for US$100,000 from a drawer and slapped it against his forehead. “Alhamdulillah (Praise be to God), they are our brothers,” the scholar quoted Mr. Tantawy, who was widely seen as a liberal reformer despite misogynist and anti-Semitic remarks attributed to him, as saying.

Separating the wheat from the chafe at Al-Azhar is complicated by the fact that leaders of the institution although wary of Salafi influence have long sought to neutralize ultra-conservatives by appeasing rather than confronting them head on.

The Al-Azhar scholars believed they could find common ground on the grounds that they and the ultra-conservatives each had something the other wanted. Beyond gaining influence in a hollowed institution, ultra-conservatives wanted to benefit from its credibility while Al-Azhar hoped to capture some of the ultra-conservatives’ popularity on Muslim streets. That popularity would help justify Al-Azhar’s long-standing support for Egyptian and Arab autocracy.

Absolute obedience

Saudi Arabia, since the rise of King Salman and his powerful son, Prince Mohammed, has, at least in the greater Middle East including Al-Azhar, largely focused on the promotion of a specific strand of Salafism, Madkhalism.

Led by octogenarian Saudi Salafi leader, Sheikh Rabi Ibn Hadi Umair al-Madkhali, a former dean of the study of the Prophet Mohammed’s deeds and sayings at the Islamic University of Medina, Madkhalists seek to marginalize more political Salafists critical of Saudi Arabia by projecting themselves as preachers of the authentic message in a world of false prophets and moral decay.

They propagate absolute obedience to the ruler and abstention from politics, the reason why toppled Libyan leader Moammar Qaddafi tolerated them during his rule and why they constitute a significant segment of both Field Marshal Khalifa Belqasim Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) as well as forces under the command of the United Nations-recognized Government of National Accord in Tripoli.

Madkhalists often are a divisive force in Muslim communities. They frequently blacklist and seek to isolate or repress those they accuse of deviating from the true faith. Mr. Al-Madkhali and his followers position Saudi Arabi as the ideal place for those who seek a pure Islam that has not been compromised by non-Muslim cultural practices and secularism.

The promotion of Madkhalism falls on fertile ground in Al-Azhar. It was part of what prompted conservative Al-Azhar clerics to call on Egyptians not to join the 2011 mass protests on the grounds that Islam commands Muslims to obey their ruler even if he is unjust because it could lead to civil strife.

Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the Egyptian-born Qatari-based scholar with close ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, unsuccessfully sought to counter Al-Azhar’s call by developing an alternative strand of legal thought that he described as fiqh al-thawra or jurisprudence of the revolution.

Mr. Al-Qaradawi argued that protests were legitimate if they sought to achieve a legitimate end such as implementation of Islamic law, the release of wrongly incarcerated prisoners, stopping military trials of civilians or ensuring access to basic goods.

Mr. Al-Qaradawi’s argument failed to gain currency among the Al-Azhar establishment. Moreover, more critical thinking like that of Mr. Al-Qaradawi barely survived, if at all, in private study circles organized by more liberal and activist scholars associated with Al-Azhar because of the risks involved in Mr. Al-Sisi’s tightly controlled Egypt.

A new kid on the block

If Saudi money was a persuasive factor in shaping Al-Azhar’s politics and to some degree its teaching, the kingdom has more recently met its financial match. Ironically, the challenge comes from one its closest allies, the United Arab Emirates, which promotes an equally quietist, statist interpretation of Islam but opposes the kind of ultra-conservatism traditionally embraced by Saudi Arabia. The UAE has scored initial significant successes even if its attempts to persuade Al-Azhar to open a branch in the Emirates have so far gone unheeded.

Mr. Al-Sisi demonstrated his backing of the UAE approach by not only acquiescing in the participation of Messrs. Gomaa and El-Tayeb but also sending his religious affairs advisor, Usama al-Azhari, to attend a UAE and Russian-backed conference in the Chechen capital of Grozny in 2016 that condemned ultra-conservatism as deviant and excluded it from its definition of Sunni Muslim Islam.

The UAE scored a further significant success with the first ever papal visit to the Emirates in February by Francis during which he signed a Document on Human Fraternity with Mr. Al-Tayeb.

The pope, perhaps unwittingly, acknowledged the UAE’s greater influence, when in a public address, he thanked Egyptian judge Mohamed Abdel Salam, an advisor to Mr. Al-Tayeb who is believed to be close to both the Emiratis and Mr. Al-Sisi, for drafting the declaration. “Abdel Salam enabled Al-Sisi to outmanoeuvre Al-Azhar in the struggle for reform,” said an influential activist with close ties to key players in Al-Azhar and the UAE.

The UAE’s increasing involvement in Al-Azhar is part of a broader strategy to counter political Islam in general and more specifically Qatari support for it. The Grozny conference was co-organised by the Tabah Foundation, the sponsor of the Senior Scholars Council, a group that aims to recapture Islamic discourse that many non-Salafis assert has been hijacked by Saudi largesse. The Council was also created to counter the Doha-based International Union of Muslim Scholars, headed by Mr. Al-Qaradawi.

There’s a big, wide world out there

Mr. Al-Sisi’s efforts to gain control or establish alternative structures and competing UAE and Saudi moves to influence what Al-Azhar advocates and teaches notwithstanding, it remains difficult to assess what happens in informal study groups. Those groups are often not only dependent on the inclinations of the group leader but also influenced by unease among segments of the student body with what many see as a politicization of the curriculum by a repressive regime and its autocratic backers that are hostile to them.

Islamist and Brotherhood soccer fans, many of whom studied at Al-Azhar, were the backbone of student protests against the Al-Sisi regime in the first 18 months after the 2013 military coup.

Unease among the student body is fuelled by the turning of Al-Azhar and other universities into fortresses and an awareness that students, and particularly ones enrolled in religious studies, are viewed by security forces as suspicious by definition, monitored and regularly stopped for checks.

“The majority of students at Akl Azhar are suspect. They lean towards extremism and are easily drafted into terrorist groups,” said an Egyptian security official. Foreign students wearing identifiable Islamic garb complain about regularly being stopped by police and finding it increasingly difficult to get their student visas extended.

A walk through the maze of alleyways around the Al-Azhar mosque that is home to numerous bookshops suggests that there is a market not only for mainstream texts but also works of more radical thinkers such as Taqi ad-Din Ahmad ibn Taymiyyah, the 13th century theologist and jurisconsult, whose thinking informs militants and jihadists and Sheikh Abdel-Hamid Kishk, a graduate of Al-Azhar known for his popular sermons, rejection of music, propagation of polygamy, and tirades against injustice and oppression.

Works of Sayyid Qutb, the influential Muslim Brother, whose writings are widely seen as having fathered modern-day jihadism, are sold under the table despite the government’s banning of the Brotherhood.

Caught in the crossfire

Caught in the crossfire of ambitious geopolitical players, Al-Azhar struggles to chart a course that will guarantee it a measure of independence while retaining its position as the guardian of Islamic tradition.

So far, Al-Azhar has been able to fend off attempts by Mr. Al-Sisi to assert control but has been less successful in curtailing the influence of Gulf states like Saudi Arabia and the UAE that increasingly are pursuing separate agendas.

In addition, Al-Azhar is facing stiff competition from a newly established Egyptian government facility for the training of imams as well as institutions of Islamic learning elsewhere in the Muslim world and Islamic studies programs at Western universities.

Al-Azhar’s struggles are complicated by the driving underground of alternative voices as a result of an excessive clampdown in Egypt, unease among segments of the student body and faculty at perceived politicization of the university’s curriculum and the blurring of ideological lines that divide the protagonists.

They are also complicated by inconsistencies in Al-Azhar’s matching of words with deeds. The institution has taken numerous steps to counter extremism and bring its teachings into line with the requirements of a 21st century knowledge-driven society. Too often however, those measures appear to be superficial rather than structural.

The up-shot is that redefining Al-Azhar’s definition of itself and the way it translates that into its teachings and activities is likely to be a long-drawn-out struggle.

James M. Dorsey

Dr. James M. Dorsey is a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, an adjunct senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute and co-director of the University of Wuerzburg’s Institute of Fan Culture.

© 2019 James M. Dorsey