Solberg’s book originated as a doctoral thesis submitted in Norway in 2013, with a catchy title: The Mahdi Wears Armani: An Analysis of the Harun Yahya Enterprise. Solberg is one of the few Western scholars who have paid close attention to this group and its ideas. Another is Stefano Bigliardi, the author of Islam and the Quest for Modern Science (Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul, 2014), who has published several articles on the topic, with a focus on Harun Yahya and science, e.g. the paper he delivered at the CESNUR conference in June 2014 or his article “Harun Yahya’s Islamic creationism: What it is and isn’t“.

Solberg starts by explaining how the name Harun Yahya attracted attention beyond Islamic circles: in 2007 a heavy and lavishly illustrated volume entitled The Atlas of Creation was freely distributed to many school libraries, educators and prominent politicians in various parts of the world. One of the consequences was that people in Europe became aware of the rise of Islamic creationism, which was mentioned as an issue of concern by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

But the books by Harun Yahya do not merely promote creationism: according to Solberg, more than 300 volumes have been published under this name dealing with a variety of topics aimed at promoting Islam. Indeed, during the 2000s works by this previously unknown author could be found in various languages in Islamic bookshops from Jakarta to London or Paris. But the omnipresence of Harun Yahya was not the result of a craze for a best-selling author: those books were not published by independent publishing houses, but by Harun Yahya’s own publishing companies. Thus the Harun Yahya phenomenon was the outcome of a global campaign to promote this author and his views—and this campaign is still under way.

Harun Yahya is actually a pen name. The real name of the man behind the publications is Adnan Oktar (born in Ankara, Turkey, in 1956). However, it is unlikely that a single person could be the author of so many books. Oktar himself claims that he is provided with material by a team of researchers; he then compiles and organizes this material into books. But Solberg considers Harun Yahya to be “a constructed persona created by a collective of individuals”, although Adnan Oktar undoubtedly approves the material, which reflects his views, since he is the central figure in the group (p. 11).

Adnan Oktar has no qualification or credentials as a religious scholar. He studied fine arts in Istanbul and trained as an interior designer. From 1979, while at university, he spoke on Darwinism, Freemasonry and the Mahdi, and thus gathered a small group of students around him, leading to the emergence of a small community recruited among affluent students in the 1980s. The group was structured formally in 1990 as the Science Research Foundation (Bilim Arastirma Vakfi, BAV). The group encountered legal problems: Oktar and 75 of his associates were arrested in November 1999 and spent time in jail. References to Harun Yahya in the early 2000s among educated people in Turkey would bring comments labelling the group as a kind of dubious and deviant “cult”.

Despite a tarnished image in Turkey, the group managed to develop an international impact, despite remaining quite small (probably 20 to 30 close associates and some 200 to 300 people involved in the group’s activities). Solberg remarks that the Internet has also helped: “Today, searching the Internet for information about Islam related to various topics is quite likely to send you to a page set up by the Harun Yahya enterprise” (p. 7). The Internet “has become an increasingly important tool for disseminating the ideas of Harun Yahya” (p. 19). Solberg rightly analyses the emergence of Harun Yahya in the context of the fragmentation of religious authority in contemporary Islam, to which new media have significantly contributed (pp. 23-25).

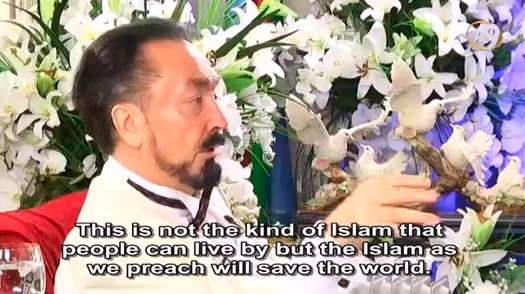

From 2007 Oktar “began assuming an increasingly more visible and public role” (p. 8). Since 2011 the group has had its own satellite television station, A9 TV, where Oktar acts as talk show host, “usually flanked by a handful of sexy, blonde, big-breasted and surgically enhanced women” (p. 9). “Oktar’s televangelism is a bewildering spectacle that challenges normative expectations of what Islamic proselytism is or should be, and it has sparked both ridicule and indignation” (p. 10). But it should be added that these shows also feature interviews with foreign guests (journalists, scholars and politicians), offering a way for Adnan Oktar to promote his views in such exchanges.

Solberg has not conducted participant observation among the group, but she provides us with a very informative analysis of its beliefs and their evolution over the years. Before her book no similar research was available. While a number of questions regarding the group itself remain open (a topic to which this review will return in its conclusion), Solberg’s book now allows us to understand both the group’s message and its roots.

A knowledge of contemporary Turkey greatly helps an understanding of the group’s origins. The famous Kurdish Muslim scholar and religious reformer Said Nursi (1878-1960) has been an important source of inspiration for Adnan Oktar (see pp. 44-50), as well as for a number of influential Turkish figures.

Solberg has identified “four key themes that have been part of the discourse of the Harun Yahya enterprise since the late 80s and early 90s: Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theories, nationalism/neo-Ottomanism, creationism and apocalypticism” (p. 20).

However, such topics have changed over time: for instance, the first book published under the name Harun Yahya (in Turkish in 1987) was entitled Judaism and Freemasonry, and claimed that Zionists were using Freemasonry for their own purposes: Solberg describes it as a work representative of conspiracy theories linking Jews and Freemasons (pp. 77-79). But today Oktar is eager to project a philo-Jewish image and frequently interacts with Israeli media, while he invites Jews and Christians to meetings sponsored by his organization. He also disavows a book published under the name of Harun Yahya about the “Holocaust myth” in 1995 and denies having authored it (pp. 79-81). He now clearly distinguishes between Zionism and Judaism (p. 85).

There has also been an opening toward Freemasonry, with representatives of the Harun Yahya movement visiting lodges, Adnan Oktar meeting freemasons and somewhat bizarre claims about his having been appointed a Grand Master—all this justified by the claim of opening a new venue for propagating Islam. But Oktar apparently remains opposed to atheistic Freemasonry. In a talk to a group of followers in April 2014, Oktar declared that “Freemasonry and the Knights Templar” will support the Mahdi: “Freemasonry will serve the Mahdi. The Mahdi will not serve Freemasonry.” (More about the Mahdi later.)

As one can see, there have been a number of changes in the group’s approach over the years – which is not unusual in religious movements around charismatic figures, as researchers know well. Outdated material is being retired, but some continues to circulate on the Internet.

Solberg mentions a small episode in the 2000s to illustrate the process of opening to other religions: in 2009 the group established links with a Jewish association, “The Re-established Sanhedrin” and had a meeting with it (p. 87). A reading of the website of the Re-established Sanhedrin makes clear that here we are dealing with very specific sections of Judaism, such as groups eager to promote the building of the Third Temple. This seems to be quite typical of the way in which circles that could be described (in purely descriptive, non-judgemental terms) as “religious fringes” of their tradition develop their own networks of interreligious relations, in ways mimicking what larger religious organizations are doing. There is no doubt that this contributes—in their own perception at least —to the development of a (mutually granted) legitimacy. Solberg correctly remarks that the interreligious opening of the Harun Yahya group paralleled wider trends taking place in Turkey at the same time, such as the interreligious efforts of the Gülen movement (pp. 87-89).

Regarding the nationalist dimension of the Harun Yahya discourse, it includes a claim that the group are the “real Atatürkists”: the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938), is presented both as a devout Muslim and a fervent nationalist, contrasting with Atatürk’s secularist image in most other pro-Islamic discourses in contemporary Turkey (pp. 94-98).

Regarding creationism, the case of Harun Yahya reminds us that it is not limited to North American Protestantism with some European echoes: in Turkey, opposition to the teaching of evolution in schools has emerged and developed since the 1970s; in 1983, Solberg reminds us, a conservative segment of the ruling Motherland Party took control of the Ministry of Education and started to criticize Darwinism, partly based on material procured from American Christian creationist organizations (pp. 119-120) – one more fascinating instance of themes circulating across religious traditions. Interestingly, while Harun Yahya does not clearly provide all the sources of his arguments, the only ones quoted to support anti-evolutionism are Western ones (p. 126).

The creationist discourse of “Harun Yahya” is part of an attempt to refute philosophical materialism (p. 143). According to works authored by Harun Yahya, Darwinism and materialism are two sides of the same coin: both promote an atheistic worldview (p. 123). Linked to materialist philosophy, evolutionism is responsible for ills such as war, violence and terrorism (pp. 121-122). Evolutionism is criticized both from a moral and scientific perspective (pp. 124-133). Fundamentally, Darwinism is described as a false religion: according to Harun Yahya this explains why it is being embraced despite the fact that it has allegedly been disproved scientifically. Logic and reason are deemed to point to the falsity of the theory of evolution, but faith in materialist philosophy leads to its adoption nevertheless (p. 135).

According to Solberg, a book such as The Evolution Deceit uses the “narrative and visual rhetoric of scientificity”: it “resembles a popularized work on science.” Quotes are mined and carefully selected in order to support the author’s views: “the theory of evolution is increasingly presented as an already discredited theory” (p. 139). “Rather than using scientific methods, Yahya employs the symbols and language of science as rhetorical devices to persuade his readers of the falsity of the theory of evolution and the truth of creation” (p. 137).

In Turkey, remarks Solberg, such a discourse can easily be propagated, since it has already been widespread through other channels. In the West it finds a receptive audience among diaspora Muslims, who welcome the nicely printed books of Harun Yahya as a source of arguments against Western secular elites (pp. 140-141).

Finally, the group has produced several volumes and some video material on apocalyptic themes (pp. 152-153). Solberg writes that the belief in the Mahdi “never became an essential part of Sunni doctrine” (p. 148), but there has been a renewed interest in apocalyptic themes in recent years, with a new generation of Muslim authors having a special interest in such topics. Regarding Harun Yahya, Solberg makes clear that the works of Said Nursi are the primary source of ideas regarding the Mahdi.

Like all millenarian groups, the group pays attention to current events as “signs of the times”. Specific features of the Turkish Sunni eschatological scenario can be discerned. Harun Yahya associates the coming of the Mahdi with a Golden Age linked to a Turkish-Islamic Union: an Islamic Union under Turkish leadership, consonant with Yahya’s neo-Ottoman and nationalist themes, will “bring peace and prosperity to all people”. Turkey’s crucial role was allegedly predicted in hadiths (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) (pp. 164-167).

The Turkish-Islamic Union “will usher forth the era of the Mahdi”, and the Ottoman era “thus comes to represent both a nostalgic past and a utopian future” (p. 173). The Mahdi is said by Harun Yahya to appear in Istanbul (pp. 155-157). Although Adnan Oktar refuses to claim this title, several texts suggest that he is actually considered as such: an impression is created that “Oktar/Yahya is not merely a commentator, but in fact the lead protagonist of these eschatological events” (p. 179).

The features and signs of the Mahdi [as described in Harun Yahya’s works] correspond with Oktar and his associates in ways that are umistakable. It is highly probably that the parallels are deliberate and that the rhetorical intention is to create an impression in the reader that Oktar is, or might be, the Mahdi. It appears, then, that the ultimate purpose of Yahya’s apocalypticism is to promote Adnan Oktar as a central figure in a battle for Islam, and to convince the audience that the da’wa [preaching of Islam; invitation to Islam] of Harun Yahya is not just any da’wa, but the cosmic struggle that has been predicted in Islamic tradition. In the discourse of Harun Yahya, Mahdim, creationism and neo-Ottomanism are fused into a particular form of Islamic apocalyptic discourse that places Turkey – and indeed Oktar/Yahya himself – at the center of a cosmic battle against the Forces of Evil ultimately leading Muslims and the world at large into a Golden Age in which Islam will rule (p. 184).

Solberg uses in the title and throughout her book the expression “the Harun Yahya enterprise”. The reason for doing so becomes clear as one progresses through the book and reaches the end of the volume: according to Solberg’s interpretation, “Harun Yahya can be understood as a religious entrepreneur”, and what started as a small, Istanbul-based cemaat (community) has increasingly turned into an enterprise for promoting not only a specific form of Islam and a creationist message, but Adnan Oktar himself (p. 185). This has become especially clear since 2009, with hints that he might be the Mahdi. And probably similar remarks could be made about some other religious groups formed around charismatic, messianic figures.

The surprising impact of Adnan Oktar can partly be explained by the fact that he has found a market niche with Islam creationism and its international propagation. Thanks to the Internet, as well as the publication and diffusion of books in various languages, the Harun Yahya enterprise attempts to create the impression that Adnan Oktar is an important Islamic figure: “What Yahya lacks in terms of authority … he seeks to compensate [for] by sheer market presence” (p. 200).

Solberg’s book provides us with a well-documented and insightful analysis of the message of Harun Yahya/Adnan Oktar. As mentioned earlier in this review, questions remain that are beyond the scope of Solberg’s research. A key issue is the ability of such a small group (at most a few hundreds followers, with a still smaller core group) to make such an impact and to be able to fund projects such as the writing and publication of numerous volumes in several languages, then distribute them across the world, either at no cost or through Muslim bookshops. Considering such small numbers of associates, it requires a group of unusually talented, efficient and wealthy people. Apparently, the enterprise is entirely self-funded through successful businesspeople recruited from the wealthiest strata of Turkish society and who are willing to support it financially (pp. 14-15). In itself, this is no small achievement and would deserve further research by people interested in contemporary religious movements. One would like to understand better who Adnan Oktar’s supporters are, what they believe, what their religious practices are, etc.

Whatever the long-term fate of the group itself, its lasting legacy will probably remain the ideas regarding creationism and eschatology that it has helped so effectively to spread and continues to promote through print and online channels. Again, this is no minor achievement.

Jean-François Mayer

Anne Ross Solberg, The Mahdi Wears Armani: An Analysis of the Harun Yahya Enterprise, Huddinge, Södertörns Högskola, 2013 (II+240 p.).

For those who wouldn’t like to order it in print, Solberg’s book can also be downloaded online free of charge, e.g. here: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/32080.