In recent years, anthropologists have paid new attention to Christianity, focusing particularly in societies that have been influenced by Western-based missionaries and churches. The editors note that the new anthropological studies of Christianity have tended to stress the rupture of conversion as a decisive influence in post-colonial societies, as, for instance, in the case of evangelical mission campaigns in many Third World countries. In contrast, Eastern Christianity is concerned with continuity, with its strong links to national identity and the way most adherents are born into the faith rather than converting from other backgrounds.

Although the book does not pretend to be a comprehensive study or survey of Eastern Christianity, the contributions, all based on extensive fieldwork, do show how Orthodox and Eastern-Rite Catholic churches are actors in the processes of nationalism, globalization and the formation of personal identity in post-socialist societies.

A chapter on the social welfare system of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) suggests that it is caught between the demands of “religious nationalism and civic nationalism.” Some social service organizations within the church have recently limited its services for Russian Orthodox believers rather than making them available for all Russian citizens. At the same time, the Russian Orthodox Church has sought to regain its legacy as a national church. Russians have widely criticized such a discrepancy, “holding the church accountable in ways that they do not for non-Orthodox congregations,” writes Melissa Caldwell of the University of California.

A chapter on of how both Orthodox believers and Muslims share shrines and festivals at some places in Macedonia and Turkey suggests that syncretism, or the blending of faiths, is a reality in borderlands between Orthodox and non-Orthodox traditions. Contemporary Muslim and Orthodox communities interact and sometimes blend outside of-and sometimes in spite of-the official positions staked out by their respective religious authorities, but such proximity can often lead to separation and antagonism, according to Glenn Bowman of the University of Kent in England.

Chapters on the growing popularity of Orthodox pilgrimages uncover the tendencies toward both religious individualism and the desire to restore a collective identity among Russians. Sociologist Jeanne Kormina of the University of St. Petersburg find that many pilgrims are not active in Orthodox parishes-some were unsure of their Christian beliefs-and view their treks to holy sites and monasteries as an individualized spiritual experience of Orthodox “authenticity.” Another study by Alexander Agadjanian of the Russian State University and Kathy Rousselet of the National Foundation of Political Science in Paris, finds that Orthodox pilgrims surrounding the newly canonized Russian royal family balance both collective and individual spiritual identities. Those venerating the Russian royal family exist outside Russia’s borders, especially due to the reunion of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia with the ROC in 2007, resulting in a transnational community of pilgrims. The pilgrims-many of whom are not strongly active in a parish-tend to show both individualist-based expressions of devotion to the royal family and a “clear desire for a strong community” with “collective identities centered around smaller or larger groups, and, eventually, the nation,” write Agadjanian and Rousselet.

The theme of the communal nature of Eastern Orthodoxy comes up again in a provocative chapter on the decline of “name day” traditions in Greece. Name days are annual celebrations of the day when a person was named after a saint at their baptisms. The day has traditionally been a communal celebration, with family, neighbors and even strangers invited to congratulate the celebrant and also commemorate the saint. Oxford University anthropologist Renee Hirschon finds that saints day are now in sharp decline in Greece, while birthdays, occasions rarely celebrated in the past, are gaining ascendency. Hirschon concludes that this change represents a shift in Greek society from a more “wholistic” Eastern Orthodox conception of the person as being embedded within a community to a Western, individualistic model-a transition that is accelerated with Greece’s incorporation into the European Union.

Richard Cimino

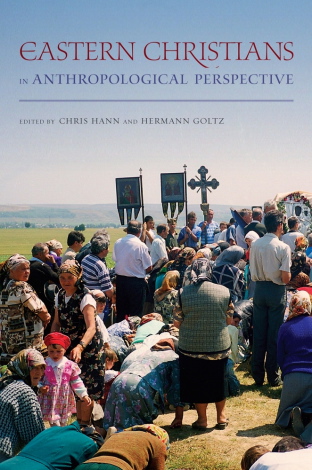

Chris Hann and Hermann Golz (Eds.), Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, University of California Press, 376 p.

Richard Cimino is the founder and editor of Religion Watch, a newsletter monitoring trends in contemporary religion. Since January 2008, Religion Watch is published by Religioscope Institute. Website: www.religionwatch.com.