This article attempts to explore the deeper dimensions of the Iranian political system in the context of the religious ideas that inform the views and behaviour of the key actors within that system. Illuminating the religious and ideological fault-lines within the regime enables a better understanding of the nature of the country’s political crisis, and the desired outcomes of the actors at the centre of that crisis.

The central contention of this piece is that there are two distinct – yet inter-related – core dynamics driving political events in Iran. The first is the perennial battle between left and right and the second the escalating battle between proponents of a complex civil society and supporters of a strong state.

The struggle between these forces is likely to unfold over a very long period – probably the first half of the 21st century – but nevertheless it is possible to outline the broad contours of a range of probable outcomes. Whilst the religious dimension of Iran’s unique system of government is likely to be modified over the long-term, it is doubtful Iran will embrace the Western secular model.

Left vs. Right

It is now accepted as conventional wisdom in both Iranian and Western academic circles that during the early post-revolutionary period Iran’s current rulers systematically eliminated their erstwhile revolutionary allies in the struggle against the Shah, thus rendering the Islamic Republic into a more cohesive and even homogeneous form. It has been consistently argued that the elimination of such unreliable and recalcitrant forces as the so-called Islamo-nationalists of the Freedom Movement, the hard secular left (embodied by the Fadayeen Khalq or the Peoples’ Sacrificiers) and the stalwart militants of the Mojahedin-e-Khalq (Peoples’ Holy Warriors), facilitated the rise of a range of elites and actors who were able to monopolize power precisely on account of their unity, if not homogeneity.

An implicit assumption inherent to this argument is that these elites were truly revolutionary – not only because they represented the strongest and most authentic strand of the revolution – but also insofar as they promised a cleaner break with the past than their revolutionary rivals. The bulk of Iranian and Western academic studies on the revolution fail to decisively position the country’s post-revolutionary elites into the myriad political, religious and ideological trends that have shaped modern Iran since the beginning of the 20th century. Moreover, they fail to adequately investigate the historical context that gave rise to these forces in the previous 19th century.

The result is that the Islamic Republic is presented as an oddity in Iran’s contemporary history, with the political-ideological heritage and antecedents of the country’s new elites either distorted or obscured altogether. Curiously this interpretation is embraced both by official historians of the Islamic Republic and the regime’s untiring enemies. It enables the latter to portray the regime as a ‘freak’ phenomenon devoid of a future, whereas it is attractive to the former insofar as it evokes a clean break from the past, thus underlining and reinforcing the revolutionary credentials of the Islamic Republic.

This flawed analysis has distorted academic studies on various aspects of the Iranian Revolution, one of which is the origin of the disputes that emerged following the eradication of outwardly non-conformist groups by the summer of 1981. The official discourse of the Islamic Republic situates these disputes in the inevitable power struggles that ensued once the dominant group in the Iranian revolution secured power in the summer of 1981. But in recent years an emergent non-official historical enquiry – enthusiastically embraced by competing factions – has started a belated forensic investigation into the genealogy of these ideological and political disputes. This effort has been energised by the post-election political crisis.

From the outset the Shia clerics who control the commanding heights of the Iranian Government divided into two core factions. The Majmae Rohaniyoune Mobarez or the Forum of Militant Clergymen (MRM) was the umbrella organisation of left-wing groups [1]. In contrast the Jame’e Rohaneeyateh Mobarez or the Society of Militant Clergy (JRM) unified the right-wing factions in the regime [2]. It is important to emphasise that both bodies are loose associations bereft of the strong cultural ethos and stringent controls typical of more conventional political organisations. However, throughout the past thirty years they have provided a platform for factional jockeying and positioning at the highest levels of the regime. In short, the MRM and JRM have mapped out the strategic direction of competing left-wing and right-wing factions in the Islamic regime.

Here it is worthwhile defining the meaning of left and right in the Islamic Republic. In the West the categories of left and right primarily define economic orientations and preferences, with the left favouring a socialist-orientated economy and the right more inclined toward free markets and a less intrusive state. In the Islamic Republic the categories of left and right are often invoked to define cultural values. This was less so in the 1980s than now but still this definition accurately captures the totality of the political experience of the past thirty years. The left is seen as less culturally restrictive and more inclined toward a liberal Islamic ethos. In contrast the right is viewed as culturally rigid, and in some cases even extreme and atavistic.

The economic dimension is also highly relevant and coincides and overlaps with this cultural dichotomy. The factions that have come to represent the so-called Islamic left are broadly speaking inclined toward Socialist economic models, whereas the Islamic right is to varying degrees allied to the Bazaar and the big merchants associated with it. But the important point is that as far as political categorisation is concerned the cultural dimension is dominant, at least from an epistemological point of view. Ironically in this respect the Islamic Republic bears some resemblance to American political culture, where left and right are often invoked to situate political actors in a cultural continuum, with the left associated with liberalism and the right with old-fashioned patriotic values.

It is also worth noting that the categories of left and right are for the most part descriptive, but nonetheless they have been consistently embraced by key political actors in the system. But absent a detailed statistical study into the self-identification of influential Iranian political actors, it is difficult to speculate with precision as to what extent these categories are descriptive or a genuine reflection of political identity.

Certainly in the heady revolutionary years of the 1980s the bulk of Iranian political actors shunned the left and right categories – and similar terminology – on the basis of their ‘Western’ origins. But by the 1990s – especially after the emergence of the reform movement and the fragmentation and liberalisation of the so-called Islamic left – these terms were being openly used by Iranian media and specialist political, economic and social publications. This was as much a reflection of the erosion of the idealism prevalent in the 1980s as it was of deepening political and ideological polarisation.

Another important caveat is to exactly what type of actors these categories are applied to. This is largely a function of the more unusual characteristics of the Islamic Republic – inasmuch as it is a revolutionary state that in some important respects defies the ideological and constitutional norms common to most nation-states – than an epistemological problem in marrying essentially Western political-economic categories to the prevailing conditions in contemporary Iran.

Broadly speaking, three types of actors can be identified: a) political; b) institutional; c) freelance. The first relates to actors who are overtly, identifiably and professionally engaged in the political process and who belong to identifiable groups and factions. The second are actors who serve in so-called revolutionary bodies such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps or specialised parts of the civil service (like Jahad-e-Sazandegi or Construction Jihad-a cross-ministerial body formed in 1979 to spearhead development projects in rural areas), but are not directly involved in politics. The third is the mass popular base of the Islamic Republic, especially the considerable strata within it who are neither professionally involved in politics nor officially connected to either the mainstream civil service or the revolutionary organisations.

The categories of left and right can be readily applied to professional political actors. However, it is with the other two groups that these categories break down and no longer provide useful or reliable markers for political identification. The media’s proclivity to increasingly identify the IRGC with the right-wing of the regime notwithstanding, it is doubtful senior Revolutionary Guards commanders (and even less so the rank and file) would see the value of this dichotomisation, let alone identify with it. As for the mass popular base of the regime, it is for the most part motivated by supra-factional considerations and is committed to the Islamic Republic as a whole.

In the 1980s the MRM and the political groups allied to it was the dominant political force in the Islamic Republic. Left-wing factions controlled the executive and judicial branches of government and also constituted the dominant force in the legislature. The chief ideologue of the Islamic left was the late Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, who from 1985 to early 1989 was the designated heir to the late Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, before being stripped of this position in March 1989 allegedly for lack of political sagacity and leadership skills. Although Montazeri was never an official member of the MRM, he had close ties with their leaders including Mohammad Mousavi Khoeiniha (chief revolutionary prosecutor in the 1980s), Mohammad Khatami (who became president of Iran in May 1997), Ali Akbar Mohtashami-Pour (a former interior minister, former Iranian ambassador to Syria and allegedly one of the founders of the Lebanese Hezbollah) and Mehdi Karoubi (former parliamentary speaker and current Iranian opposition leader).

The main non-clerical figure of the Islamic left was Mir Hossein Mousavi, who was the Islamic Republic’s Prime Minister throughout the 1980s. Mousavi was removed from his post in August 1989, merely two months after the demise of Grand Ayatollah Khomeini, and subsequently disappeared from the public sphere, only to re-emerge two decades later to contest the presidency. His controversial defeat by incumbent President Ahmadinejad plunged the Islamic Republic into its gravest political crisis to date, with Mousavi catapulted into the unlikely role of chief oppositionist.

Whilst the so-called Islamic left is today associated with liberalism, back in the 1980s they were better known for their radicalism. This was exemplified by the premiership of Mir Hossein Mousavi, which was characterised by strong socialist economic policies and the dramatic intrusion of the state into previously private spheres of economic, cultural and personal activity.

While Mir Hossein Mousavi was an economic and political radical, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri – and more to the point the people around him – was associated with religious zeal and eccentricity. Matters came to a head in September 1987 following the execution of Mehdi Hashemi, the brother of Montazeri’s son-in-law and a key aide to Ayatollah Khomeini’s designated successor. One of the founders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, Hashemi led a quasi-military unit called the “Bureau of Assistance to Islamic and Liberation Movements”. Loosely associated with the IRGC, this non-official Bureau took it upon itself to provide moral and material support to pro-Iranian insurgent groups in the Middle East and beyond. By the mid-1980s Hashemi was judged to be out of control and the regime quickly facilitated his downfall. Reports emerged of his criminal past and loose association with the notorious SAVAK (the Shah’s secret police). Specifically, Hashemi was accused of committing a range of felonies, including masterminding the assassination of the Isfahan-based senior cleric Ayatollah Shams-Abadi in the 1970s. The downfall of Mehdi Hashemi and the Bureau which he led (officially referred to as the ‘Mehdi Hashemi gang’) was the first and so far only instance of a bloody purge in the Islamic Republic [3].

The late Grand Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri and his closest followers sided with Mehdi Hashemi to the bitter end, claiming that he had been punished for exposing the Iran-Contra scandal to the Lebanese political magazine Ash-Shiraa in November 1986 [4].

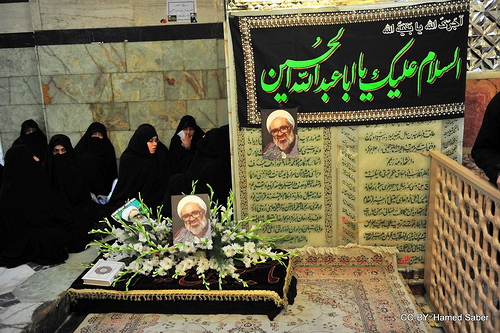

This saga is noteworthy, if only to underline the questionable nature of the support and admiration directed at Montazeri since early 1989. Following his dismissal by the late Grand Ayatollah Khomeini in March 1989, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri was propelled to the role of chief clerical oppositionist to the Islamic Republic, a state led by Shia clerics. Moreover, his cause was championed by both religious and secular Iranian dissidents and also increasingly by powerful political and media circles in the West. The level of admiration showered on this recently deceased enigmatic and hapless cleric fluctuated to the extent that he distanced himself from the ideas and the regime which he had once championed. His chequered political past – and more importantly his strong ties to the most extreme elements in the Islamic Republic – was conveniently forgotten.

The JRM and the factions that are referred to as the Islamic right managed to oust the MRM and the left-wing following the demise of Grand Ayatollah Khomeini in June 1989. But even in the 1980s this umbrella body was a powerful force that often blunted the more radical economic programmes of the Islamic left. The most prominent leaders of this body have included Ayatollah Seyed Ali Hosseini Khamenei (who was president for much of the 1980s and subsequently became the leader of the Islamic revolution), Hojatoleslam Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (parliamentary speaker in the 1980s and president in the 1990s), Ayatollah Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani (former interim prime minister and a former close aide to the late Ayatollah Khomeini) and Hojatoleslam Hassan Rowhani (former deputy parliamentary speaker, former chief nuclear negotiator and one of the most influential figures in the Iranian national security establishment).

Ayatollah Seyed Ali Khamenei is believed to have long relinquished his post in the JRM and is no longer affiliated to it. The same is often said about Hashemi Rafsanjani. Broadly speaking, the JRM promotes a conservative interpretation of Islamic beliefs and rulings and espouses a more open economy, albeit one dominated for the most part by the monopolistic Bazaari merchants.

Since the early 1990s new right-wing factions have emerged on the scene, only to clash with more conservative right-wing forces, particularly those affiliated to the JRM. Interestingly these new factions often mix the hard-line Islamic rhetoric associated with the right with the egalitarian economic programmes of the left. This is particularly the case with the faction behind Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the Islamic Republic’s outspoken and controversial president. The chief religious ideologues of the hard-line Islamic right are Ayatollahs Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi and Abdollah Javadi-Amoli. The former is accused of being a member of the shadowy Hojattieh Society, a controversial ultra-Shia organisation that was strongly and repeatedly condemned by the late Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Mesbah-Yazdi has strenuously denied any association with Hojattieh. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was also initially implicated in membership in the Hojattieh, but no reliable evidence was offered to support the accusation.

The relationship between the semi-clandestine Hojattieh Society and the Islamic Republic has been the subject of considerable speculation, misreporting and downright disinformation. Founded in the early 1950s by Sheikh Mahmoud Toolayee (Halabi), the Hojattieh Society was originally a single-issue organisation that campaigned against the Bahai faith [5]. The group was opposed to the involvement of pious Muslims in Government, and as such Halabi found himself in disagreement with the concept of Velayat-e-Faqih (Rule of the Jurisconsult) the essential philosophy and ideology of the late Ayatollah Khomeini and later the foundational legal, political and ideological core of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Notwithstanding this opposition, Halabi and his followers welcomed the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and paid lip service to the leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini. However, by the summer of 1983 the group had been disbanded, following strong rhetorical attacks by Ayatollah Khomeini. Factually speaking, the only proven Hojattieh member who has held official positions at the highest levels of the post-revolutionary Iranian Government is Ali Akbar Parvaresh, who was minister of education in the early and mid 1980s before falling into obscurity. Absent reliable information to the contrary, allegations of Hojattieh infiltration into the highest reaches of the Islamic Republic amount to little more than rumours. Nonetheless, the Hojattieh Society (or politicised sections of what remains of it) can be situated on the right side of the political spectrum.

Despite noteworthy levels of interpenetration and convergence of political and economic discourses, the bulk of political actors in the Islamic Republic have consistently engaged in divisive politics, thus stunting the growth of a more transparent and accountable polity. The creation of the Islamic Republican Party in 1979 was designed to transcend factional interests to create a cohesive political society, but this political entity never formed into a disciplined political organisation. In fact it turned into yet another forum for factional divisions and was dissolved on the orders of the late Ayatollah Khomeini in June 1987. Apparently the factionalised nature of the regime was too profound for disciplined political parties to take hold.

A semblance of stability – and a medium for counselling and dispute-resolution – came in the wake of the emergence of ‘centrist’ factions under the leadership of pragmatic cleric Hojatoleslam Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who is at heart a conservative oligarch, but does not fit neatly into the left/right dichotomy. In the 1980s the Western media presented Rafsanjani as a moderating force in the face of a radical left-wing Government led by Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi and the conservative and right-wing factions that were trying to thwart him.

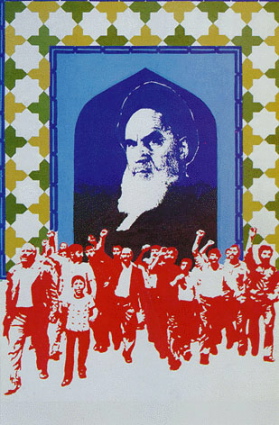

This divided political society should not cloud judgements into the nature of the regime that emerged out of the Islamic Revolution. Too often in the past thirty years political pundits and analysts have predicted the demise of the Islamic Republic based on the factionalised and divided nature of the post-revolutionary political system. This observation fails to take into account the mass popular base of the Islamic Republic and the ideological cohesion of Islamic Republic loyalists. Despite inevitable political differences the ideological constituency of the Islamic Republic is motivated by supra-factional considerations, such as the original values of the Islamic Revolution and a strong desire to safeguard the political and strategic ‘achievements’ of the past thirty years. Broadly speaking, Islamic Republic loyalists recognise each other on the basis of a shared political/ideological lexicon, attachment to a highly idiosyncratic revolutionary political culture borne out of the struggle against the Shah’s regime and the battlefields of the Iran-Iraq War and an unflinching commitment to the perpetuation of the Islamic Republic.

The regime and its leaders readily attest to this mass ideological base as their key political and strategic asset. This recognition even informs the national security doctrine of post-revolutionary Iran. For instance, in trying to achieve strategic parity and equilibrium with more powerful non-indigenous forces in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East as a whole, the Islamic Republic often cites the loyalty of its followers – and their assumed readiness to commit the ultimate sacrifice for the sake of the revolution – to deter aggression by its enemies. The spectre of mass self-sacrifice is raised to project the Islamic Republic as an undeterrable state and thus enable Iranian leaders to assume an enhanced strategic role in the region and beyond which does not correspond to the actual political, economic and military strength of the country.

Velayat-e-Faqih: an institution in crisis

The concept of Rule of the Jurisconsult or the Guardianship of the Jurist, as it is more commonly called, forms the pillar of the post-revolutionary Iranian state. This is the concept that justifies and enables the domination of the state by senior Shia clerics and their laymen allies.

The origins of the modern concept of Velayat-e-Faqih dates back to the late 18th century to a socio-religious milieu that was heavily influenced by the Safavid dynasty, Iran’s rulers from 1502 to 1722. The Safavids transformed the Iranian religio-demographic landscape by converting the majority of the population from Shafii and Hanafi schools of Sunni Islam to the Shia Jaafari faith. They also made Twelver Shiaism the state religion and promoted the development of a Shia clerical class. Whilst at the beginning this clerical class was close to the Safavid state, with the passage of time it became increasingly independent, to the point of becoming fundamentally different from Sunni Ulama (clerical class), who have always been close to centres of political power.

In a nutshell Velayat-e-Faqih holds that in the absence of the Twelfth Imam, Abul Qasim Mohammad ibn Hasan ibn Ali (aka Mohammad Al-Mahdi- born approximately 869 AD), whom Twelver Shia Muslims believe disappeared into Ghaybat or ‘occultation’ at the end of the 9th century AD, governance of the Muslim community ought to be entrusted to the most learned and qualified of the Ulama [6]. According to Shia doctrine the Mahdi will return at a point when the world is gripped by corruption and injustice, to spearhead the salvation of mankind. Therefore, the historical and ontological function of Velayat-e-Faqih is to fill a major religious and spiritual vacuum and provide leadership to the faithful in the absence of the ‘Hidden’ Imam.

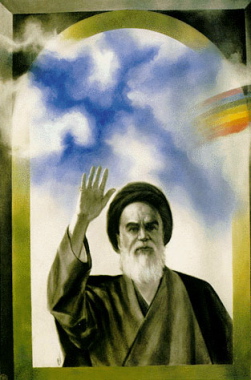

The extent of the authority exercised by Velayat-e-Faqih has been the subject of considerable debate amongst its proponents. Broadly speaking, there are two schools of thought; one which limits the role of Velayat-e-Faqih to mostly religious or at least non-political matters and the other which entrusts it with full governance over the Muslim community or any territory where Muslims form the clear majority. The theory of Velayat-e-Faqih lay dormant for more than a century before it was revived by the late Ayatollah Khomeini in a series of lectures in the 1970s (later published in book form). Ayatollah Khomeini subscribed to the latter interpretation and consequently transformed Velayat-e-Faqih into an all-encompassing religious-political theory, capable of governing major modern nation-states. Indeed, the concept of Velayat-e-Faqih is the most outstanding legal innovation in the post-revolutionary Iranian constitution. In short, it forms the religious, political and juridical backbone of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Throughout the 1980s the institution of Velayat-e-Faqih was bound up with the unique charisma and near-universal popularity of the late Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Ayatollah Khomeini’s towering leadership masked Velyat-e-Faqih’s theoretical and practical weaknesses – in particular its lack of practical harmony with other institutions of state – from public view. But this changed dramatically following Khomeini’s demise in June 1989, after which the Majlis-e-Khebregan (or Assembly of Experts-the body tasked with selecting and monitoring the Valiyeh Faqih, or Ruler-Jurisconsult) appointed Hojatoleslam Seyed Ali Hosseini Khamenei (Iranian President from 1981-1989), a relatively junior cleric, to the post of Valiyeh Faqih. This appointment overrode one of the key criteria guiding accession to the position of Valiyeh Faqih, namely supreme jurisprudential knowledge and experience. But revisions were made to the constitution (via a referendum) in July 1989 to remove this criterion. Notwithstanding the lack of appropriate levels of scholarly knowledge, it was widely felt within the Assembly of Experts, other clerical bodies, and across the regime and amongst its supporters as a whole, that Seyed Ali Hosseini Khamenei – on account of his vast political experience and proven leadership skills – was the most qualified candidate for the post.

The experience of the past twenty years has steadily exposed the weaknesses of Velayat-e-Faqih, both as a religious concept and a political institution. From a religious point of view, a growing number of Shia clerics – including some senior ones – have openly questioned the legitimacy of this institution, especially in its more authoritarian form, the so-called Velayat-e-Motlagheyeh Faqih (or absolute rule of the jurisconsult). A growing number of the clerical classes in the major learning centres of Shia Islam, especially in Qom in Iran and Najaf in Iraq, have expressed concern that the shortcomings of the Iranian regime may become synonymous in the public’s mind with inherent shortcomings in Velayat-e-Faqih and by extension Shiaism as a whole.

In the political sphere, the role of Velayat-e-Faqih has become increasingly contentious inasmuch as Ayatollah Seyed Ali Khamenei has been steadily identified with the right-wing of the regime. The reformists (the political successors of the Islamic left of the 1980s) have consistently alluded to this development to call for reforms to the extent of powers exercised by the Valiyeh Faqih. From the reformists’ point of view, one of the key characteristics of the Valiyeh Faqih – namely political impartiality – has been eroded by Khamenei’s sometimes partisan approach toward dispute resolution.

The real problem with Velayat-e-Faqih is not that it is ill-defined as an institution, but that its constitutional definition does not suit the institutional and political configuration of the Islamic Republic. It is precisely because of this mismatch that the current Valiyeh Faqih finds it increasingly difficult to act as an honest broker and arbiter between the left and the right. In short, Velayat-e-Faqih is faced with a long-term legitimacy crisis; one which is likely to escalate once the current Valiyeh Faqih departs the arena.

Post-election crisis

The political crisis triggered by the controversial presidential elections of June 2009 is a reflection of two profound and inter-related factors; first the dramatic ideological and political transformation of the Islamic left and second the growing homogenisation of the Islamic Republic and the collapse of the factional political order.

Following the ending of the Iran-Iraq War in 1988 and the demise of revolutionary leader Grand Ayatollah Khomeini a year later, a tentatively ‘reformist’ movement took shape within the inner sanctums of the Islamic Republic. Led mostly by former security and intelligence personnel this reform movement drew much of its ideological and political strength from the left-wing factions in the regime, in particular the most radical ones [7]. The reform movement came to power in May 1997 following the dramatic victory of Mohammad Khatami (a key MRM leader) in that year’s presidential election.

Whilst the political actors who assumed power in May 1997 were the same people who dominated the political scene in the 1980s, it was evident that their political rhetoric – and indeed their entire philosophical and religious outlook – had undergone a dramatic and for the most part sincere transformation. The new Islamic left now championed fully-fledged liberal democracy, albeit one with mild religious qualifiers. Whilst the reformists went out of their way to reconcile their discourse with the foundational values of the Islamic Revolution, to the right-wing factions and the bulk of Islamic Republic loyalists, they had transgressed the ideological and religious boundaries of the revolution.

The reformists were ousted from power in the June 2005 presidential elections but emerged in full force to contest the 2009 presidential elections, this time under the leadership of former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi. Assuming that the left and right could no longer contest politics within existing constitutional and institutional arrangements, the key power centres of the regime were faced with two stark choices; either to open up new political spaces or escalate repression. They opted for the latter, thus plunging the country into a political crisis.

Not surprisingly the eradication of the reformists has exposed divisions amongst the right-wing factions, particularly those who are not impressed by the idiosyncratic leadership-style of President Ahmadinejad. These ‘centrist’ right-wing factions probably articulate the feeling of the majority of Islamic Republic loyalists toward the political crisis, namely that its violent moments were avoidable and that the reformists have a key role to play in politics and society, despite their estrangement from some of the foundational values of the Islamic Revolution. Arguably the most articulate spokesman of this trend is Saeed Abutaleb, a former parliamentary deputy, well-known filmmaker and a veteran of the Iran-Iraq War [8].

State vs. Society

Another important dimension of the political crisis is the struggle between the proponents of a strong state and the champions of a vibrant civil society. The battle between left and right in the Islamic Republic is steadily shifting toward this fault-line. Both sides of the political spectrum strenuously claim that their position is consonant with the foundational values of the Islamic Revolution.

Right-wingers argue that one of the long-term aims of the 1979 revolution is to end Iran’s historical decline and to once again propel the country into a dominant geopolitical position in the region and perhaps even beyond. They argue that the Islamic Republic is well on its way to achieving this aim and is set to inflict an historic strategic defeat on its arch-foe the United States in the Persian Gulf and the wider Middle East [9]. In defending these claims, the proponents of a strong state cite Iran’s towering ideological and spiritual presence in the region and quote credible facts and statistics which outline Iran’s growing defence and technological capabilities as well as the country’s deepening security hegemony in the Middle East.

Meanwhile the champions of a more diverse and vibrant civil society argue with equal conviction that one of the cardinal objectives of the revolution was to end all forms of despotism and discrimination in Iranian society and by doing so setting an example to neighbouring countries and the Muslim world as a whole. Inspired for the most part by reformist religious doctrine, the defenders of civil society bemoan the democratic deficit in the Islamic Republic and resent the towering influence of Velayat-e-Faqih. This constituency calls for the empowerment of every noteworthy component of Iranian society within the constitutional framework of the Islamic Republic. Insofar as they call for amendments to the constitution, this is invariably qualified by repeated emphasis on the use of exclusively legal and non-violent means to achieve that end [10].

While the state/society debate in its current ferocious form is relatively recent, its genealogy can be traced to factional posturing throughout the history of the Islamic Republic. In the 1980s the dominant left-wing factions were mostly interested in reforming Iranian society in the wake of the downfall of the monarchy, which had ruled Iran intermittently for more than two millennia. To the Islamic left ‘Islamisation’ of society was synonymous with creating more egalitarian economic structures and bridging the wealth gap between the social classes, and between the countryside and the urban centres. Whilst the left did not openly embrace social diversity, it did not rule it out either, provided it didn’t come at the expense of economic equality.

In the 1990s, following the ascendance of the Islamic right, the focus shifted toward creating a strong state, particularly in the wake of the Iran-Iraq War which had consumed much of the country’s strategic and economic resources. Broadly speaking, the political measures undertaken in that decade were mostly geared toward strengthening the state, sometimes at the expense of civil society.

From 1997 to 2003, during the ascendancy of the reformists, the two approaches consistently collided as they were being pursued simultaneously. Whilst the two discourses are not mutually exclusive, the ferocity with which they were pursued inevitably produced regular clashes. The outcome of the June 2009 presidential elections decisively favoured state-centric political forces, albeit temporarily. Indeed, the divisions at the heart of Iran’s political society are now so profound that tensions and crisis are likely to emerge on a consistent basis for the foreseeable future.

Notwithstanding the complexity of Iran’s political crisis, the ongoing struggle between state-centric and society-centric discourses is where the key political battleground is situated. It is the cutting-edge conceptual space where all the political tensions and divisions collide and culminate. The challenge for all the political actors involved is to manage the struggle to the point where the quest for social complexity and a strong state become mutually reinforcing.

What likely lies ahead is a two to three-decade political and social struggle where the underlying forces constantly jockey and manoeuvre for position. Whilst predicting the outcome at this point would be foolish, two things are relatively certain. First, given the maturity and sophistication of Iran’s political society, the non-communal nature of the political divisions and the proven resilience of the country’s institutions, this struggle is unlikely to become violent. Second, the underlying constitutional integrity of the Islamic Republic is unlikely to be violated or changed and modified suddenly by non-consensual means.

The key question is what is likely to happen to the overtly religious institutions at the apex of the Iranian political system, chiefly the Velayat-e-Faqih. Whilst modification to these institutions over the long-term looks inevitable, there is no compelling reason to believe that they will not survive in one form or another. Certainly the bulk of the reformists have not – as of yet anyway – called for their removal. Nor have they suggested that the existence of Velayat-e-Faqih per se is incompatible with representative and democratic government. The debate at present centres on what type of Velayat-e-Faqih is most suitable; with the right-wing favouring the status quo and the left calling for modifications, with some suggesting that the institution should be reduced to a ceremonial role.

In the final analysis, it is important to note that the ultimate desired outcomes of both constituencies are not fundamentally dissimilar. Both sides espouse a representative form of government that is rooted in the foundational values of the 1979 revolution and one which is at least outwardly different to prevailing Western political models. Given this underlying – albeit under-stated – commonality of outlook it can not be ruled out that Iran may yet achieve a genuinely representative form of government that is at the same time strikingly different to the Western secular model.

Mahan Abedin

Notes

[1] Although it was officially formed in the summer of 1987 the MRM’s ideological and organisational roots can be traced to the very early days of the revolution.

[2] The JRM was founded in late 1977, however it only crystallised into a recognisable umbrella organisation in the early 1980s.

[3] Doubtless observers could point to other instances, notably the execution of Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, a once key aide to the late Ayatollah Khomeini and Iranian foreign minister (1979-1980), who was executed in September 1982 following a 26-day day trial during which he was accused of trying to organise a coup. But unlike Mehdi Hashemi Ghotbzadeh never belonged to the inner circles of the Islamic Republic and did not subscribe to Islamist ideology. Indeed, he was more inclined toward the old National front and its mildly religious splinter group the ‘Freedom Movement’, both of which are treated as non-conformist by the Islamic Republic.

[4] For an in-depth treatment of this highly contentious aspect of the Islamic Republic’s history refer to Hojatoleslam Ahmad Salek’s interview with Rajanews, a right-wing and pro-Ahmadinejad news and analysis website: http://rajanews.com/detail.asp?id=47259. Entitled “A Forensic Scrutiny of the Mehdi Hashemi Gang” the interview highlights the continued importance of these ostensibly historical debates to contemporary Iranian politics. Hojatoleslam Ahmad Salek is a leading clerical figure in the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps. He was the first commander of IRGC forces in Isfahan. Later he briefly commanded the Basij, the IRGC’s paramilitary unit. He has also held posts in the Iranian foreign ministry where he was in charge of communication with ‘liberation movements’ and has served on various oversight and audit bodies, including the National Vetting Organisation, which he presided over. Hojatoleslam Ahmad Salek is widely believed to be the most powerful ideological (if not executive) force in the IRGC’s myriad intelligence and security organisations.

[5] For a near exhaustive repository of Sheikh Mahmoud Toolayee’s and other Hojattieh Society leaders’ speeches (in audio form) refer to the following site: http://qaaem.com/Old_Site/doc_sound_sokhanrani_tavlaaie.htm.

[6] Shia Muslims make a distinction between Ghaybat Al-Soghra (minor occultation) and Ghaybat Al-Kobra (major occultation). During the former period the Mahdi reportedly kept in touch with his followers via deputies, the last of which was Abul Hasan Ali ibn Muhammad al-Samarri. The latter period is believed to have begun after Al-Samarri’s death in 941 AD, after which the Mahdi severed all links with humanity

[7] For a comprehensive survey of the origins of the reform movement refer to the author’s: “The Origins of Iran’s Reformist Elite”, Middle East Intelligence Bulletin, Vol 5, No 4, April 2003.

[8] For an in-depth insight into Abutaleb’s perspective on the political crisis and his proposed solutions refer to the following interview entitled: “Those who shout the loudest: Where were they during the war?”

[9] This viewpoint is most forcefully made by Dr Hassan Abbasi, a leading right-wing ideologue and the director of the Centre of Borderless Doctrinal Analysis. In this interview, entitled “The current situation of the Islamic Republic is akin to being the world’s heartland“, Abbasi outlines the factors and challenges that are propelling the Islamic Republic toward the status of a global power.

[10] For an articulate exposition of competing social and political forces in contemporary Iran refer to Hamid-Reza Jalaipour’s “A survey of Iran’s crisis-ridden political society and its future“. A former IRGC commander, Hamid-Reza Jalaipour is one of the pioneers of the reform movement. He is now a sociologist and political commentator.

Mahan Abedin is a research fellow at the New Delhi-based Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis. Previously he has worked with numerous think tanks, including the Washington-based Jamestown Foundation and the London-based Centre for the Study of Terrorism. He has also been active in journalism, having worked for the Beirut-based Daily Star and most recently the Irbil-based AK News Agency where he was chief editor of the Persian and English sections. Born in Iran, but raised and educated in the United Kingdom, Abedin is a frequent traveller to the Islamic Republic where he is a consultant to independent media.

© 2010 Mahan Abedin