Marshall traces the long history of evangelical missions and churches in Nigeria, noting that Pentecostalism was imported into the country only two decades after the birth of the movement in Los Angeles in the early 1900s. But it was in the 1970s that the first wave of evangelical growth swept the country through such American groups as Scripture Union and denominational missions, such as those run by the Baptists and the Assemblies of God. These evangelicals tended to be adopt a strict separation from “worldly” activities and a simple and austere lifestyle. But that changed drastically in the 1980s and 1990s when prosperity teachings became the Pentecostal trademark, with these churches expanding rapidly into all sectors of society.

Marshall writes that the prosperity gospel, teaching that Christians can claim healing but also financial blessings, came from Pentecostals in the US (and known as the “faith movement”), but it accompanied and answered dilemmas caused by the economic boom in Nigeria during the 1980s and 1990s, such as the growth of individualism and the deterioration of the structure of kinship. Many Pentecostals were no longer willing to forsake the wealth and influence of mainstream society, even after Nigeria suffered a steep economic decline in the 1990s. In fact, the poverty and the related high rate of political corruption and violence in the country only propelled Pentecostalism into a more prominent place in Nigerian society.

It was during this time that Pentecostal churches became actual financial empires; the laws (and lack of laws) encouraged prominent clergy to establish their megachurches as businesses where their earnings would be inherited and controlled along family lines. For example, the late pastor and televangelist Benson Idahosa’s Church of God Mission International included a stadium, a hospital, a private university and a bank, not to mention the wealth and property owned by family members around the world. Marshall also shows how Nigerian Pentecostalism is a global phenomenon, not only because its churches, such as the Redeemed Christian Church of God, are spread through a growing Nigerian diaspora, but also because of these believers’ effective use of media (especially videos and DVDs) to spread their message of miracles and prosperity.

Although not unique to Nigerian Pentecostals, their other emphasis on “spiritual warfare” and battling demonic influence has a special meaning in a society where occult ritual crimes and killings occupy the headlines along with gang violence and Internet scams. Marshall writes that the Pentecostal stress on miracles and demonstrating God’s power through healings and prosperity exists side-by-side with sorcerers and “witches” claiming similar supernatural powers. In such a situation, Pentecostals can face suspicions-often fanned by rival preachers and churches-that they are colluding with evil forces in their miracle-working–an accusation that had led to cases of mass violence. The fear of the Islamic revival in the north of the country has likewise been cast by many Pentecostals as a force of evil that has to be excluded from the “Christian nation.”

Marshall obviously doesn’t agree with Nigerian Pentecostal preachers that their faith is a healing and unifying force in the country. She sees the Pentecostals’ exclusiveness and the rivalry between churches which lack any cooperative structure as reflecting the atomization and near- entropy of the nation itself. But she is also critical of anthropologists who see Pentecostalism mainly as an oppressive Western import that is preventing “authentic” African traditions and politics from developing. She argues that the Pentecostal revival, for all its faults, has allowed Nigerians to recreate and seek to free themselves from a collective past that carried its own forms of subjection and domination.

Marshall concludes that it is particularly the growing number of Pentecostals following such leaders as Tony Rapu, of the organization known as This Present House–Freedom Hall, trying to create a third way between the strict separatism of the earlier wave and the prosperity gospel of today who may best be able to create a civil society with a degree of justice for all of Nigeria’s citizens.

Richard Cimino

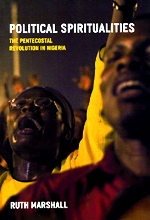

Ruth Marshall, Political Spiritualities: The Pentecostal Revolution in Nigeria, University of Chicago Press, 2009, 360 pages.

Richard Cimino is the founder and editor of Religion Watch, a newsletter monitoring trends in contemporary religion. Since January 2008, Religion Watch is published by Religioscope Institute. Website: www.religionwatch.com.