The results of Sunday’s vote were unexpected for most observers, including the editors of this website. Recent surveys forecast that the popular initiative for the ban of new minarets in Switzerland would be rejected by 53 per cent of the voters (with less than 40 per cent supporting it and the rest remaining undecided). It is true that growing support for a ‘yes’ vote had been observed during the last weeks of the campaign, but not of such a magnitude: nobody – even its supporters – had counted on such massive support for the ban on minarets.

Usually, Religioscope does not comment on hot news and prefers to keep some distance from the events of the day. However, since our website is located in Switzerland and since the Religioscope Institute published a book (in French) on the minaret controversy in September entitled Les Minarets de la Discorde, it seems appropriate to offer an assessment, primarily for the purpose of answering the questions of readers across the world. Issues raised by the vote indeed go beyond Swiss borders.

But let us first explain what a ‘popular initiative’ is, and how the initiative for banning minarets came into existence.

The ‘popular initiative’ against the building of minarets

In the Swiss system of semi-direct democracy, a ‘popular initiative’ must be distinguished from a ‘popular referendum’. At the federal (national) level, a popular referendum can be held against a law or a treaty voted for by the Federal Parliament. Within six months, at least 50,000 citizens must sign the referendum (the validity of the signatures is verified). Beside the popular referendum, there is also a compulsory referendum: when a change is made in the Federal Constitution, citizens are asked to vote for or against it.

A popular initiative is something different: a group that manages to gather at least 100,000 signatures of citizens within 18 months can force a national vote for introducing a change into the Federal Constitution, even without any support within the Federal Parliament. The government can decide to send the initiative to a national vote either with or without a counter-proposal. In order to be accepted, it is not enough for a popular initiative to gather a majority of individual votes: since Switzerland is a federal system, a referendum must also win a majority of the cantons, i.e. the units of the federal state (some of which are significantly more populous than others).

The popular initiative against the building of minarets was launched after local controversies arose around projects to add small, ‘symbolic’ minarets to the top of a few Muslim places of prayer (former commercial or industrial premises converted for religious purposes). The promoters of the initiative managed to gather 115,000 signatures, which were presented to the Federal Chancery in July 2008. The initiative – which has become law in Switzerland after the 29 November 2009 vote – adds a paragraph (paragraph 3) to Article 72 of the Federal Constitution stating that: ‘The building of minarets is forbidden.’

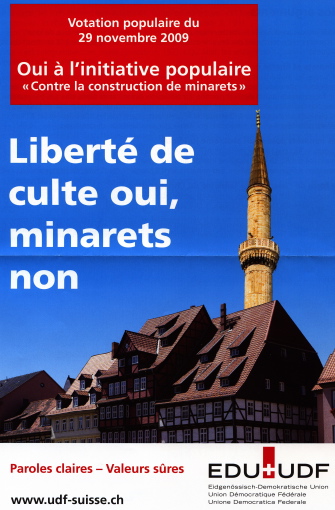

The initiative was primarily supported by members of the Swiss People’s Party (Schweizerische Volkspartei in German; Union Démocratique du Centre in French), a rightist political party that currently forms the largest parliamentary group in the Swiss Federal Parliament, and of the Federal Democratic Union (Eidgenössisch-Demokratische Union in German; Union Démocratique Fédérale in French), a small, but quite active evangelical and conservative political party (Religioscope published a study in French on this group before the 2007 federal elections).

Both the government and a majority of the Federal Parliament had requested voters to reject the popular initiative. Similarly, the Roman Catholic Church and the Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches had strongly recommended rejection of the initiative. Even the main evangelical organizations had adopted the same stance, while most of the media were clearly against the initiative.

Nevertheless, the initiative was eventually supported by a majority of the voters (with a participation rate of more than 50 per cent being considered as quite good by Swiss standards). It was not the first time that a majority of Swiss people had gone against the recommendations of most political and religious organizations; however, the case of the vote on minarets is striking because of the very clear result (i.e. it was not a victory by a tight margin) on a potentially very sensitive topic.

Initial observations after the acceptance of the initiative

Practically, what does this vote mean now? There are currently four minarets in Switzerland, and nothing will change for these, as only the building of new minarets is forbidden. It is also important to state that there is no restriction on building mosques or other Muslim gathering places; the law applies to minarets and only to them. In the same way, there will be no restrictions on Muslim worship as it has been conducted up until now.

One question raised within hours after the successful outcome of the initiative was the likelihood of a case being brought to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg. For instance, a Muslim group denied the right to build a minaret in a town where one has been planned (for instance, in Langenthal) could make recourse to the ECHR. It is quite possible that this will take place sooner or later (although such a process may take several years to reach completion). There would definitely be arguments to condemn Switzerland, but it is impossible to know with certainty at this stage what the final decision would be, in the light of past decisions of the ECHR on a variety of issues with a religious component.

Behind the rejection of minarets, there are larger issues – e.g. questions and fears about Islam itself or about the presence of Muslims in the country – and the minaret has become a symbol around which all these issues have crystallized. In the eyes of the sponsors of the initiative against minarets, these Islamic towers are the expression of a movement towards political domination. Proponents of the initiative have always taken care to emphasize that they were not acting against religious freedom, since mosques can exist perfectly well without a minaret, and in any case Swiss minarets are not supposed to be used for calling people to prayer. Far from being limited to the issue of the minaret itself, the campaign debates dealt with Islam in general. The supporters of the ban have made the minaret into a symbol of what they see as the Islamization of Switzerland and Europe.

As mentioned earlier, a major surprise has been the huge discrepancy between the results of the vote and the forecasts made by political surveys prior to its taking place. This puts seriously into question the reliability of such surveys when they deal with issues where voters perceive a wide gap between their own views and those of a majority of dominant elites and the media, thus possibly making them reluctant to express their opinions openly. A few hours before the results of the vote were announced, at a time when it was still unexpected that the initiative would win, a representative of the Swiss People’s Party in the Federal Parliament, Oskar Freysinger, was telling a television crew that a ‘yes’ vote for the initiative would be the equivalent of a denial of the whole Swiss establishment (political parties, major churches, media, etc.); no doubt he was making a valid point. This raises quite serious issues regarding the gap between the establishment and the average Swiss citizen, especially when even government agencies had not been able to predict the outcome.

Why did people vote for banning minarets?

While in the months to come we can expect detailed analyses to reveal more about the motivations of voters, it can almost certainly be said at this stage that the vote did not reflect one view alone, but a variety of concerns that combined in various ways to produce the outcome. Without being able at this point to precisely assess the relative importance of each factor, we can already list the following ones:

• There are circles and people who are developing an ideological critique of Islam. In this time of instant communications, such circles and people easily interact with one another across borders, particularly over the Internet. They do not all share the same worldview: some have a secular approach, while others have a more religious (Christian or Jewish) approach. Such core groups of critics of Islam may not have many registered followers, but to a large extent they provide the arguments that then become used as ammunition in political debates. An instance would be the Swiss Movement against Islamization (Mouvement Suisse contre l’Islamisation). These groups find receptive ears in some segments of the Swiss People’s Party, as well as within the Federal Democratic Union (with the latter being critical of Islam while expressing strong support for Israel and Zionism, which are seen in the light of Biblical prophecy: many of its members could be described as Christian Zionists). These movements all share the same understanding that the development of Islam in Europe equates to a non-military invasion that will ultimately lead to the enforcement of Islamic domination and the establishment of an Islamic legal system. For them, banning minarets means sending a strong signal of the need to stop such trends.

• There are also people who are concerned about immigration in general. Switzerland is a country where emigration has historically been strong, but it has never seen itself as a country favouring immigration. In the 1960s and 1970s, immigrants from Southern Europe coming to work in Switzerland (where they had actually been invited in order to meet the needs of industry and construction work) had been met with strong movements of hostility against ‘foreign overpopulation’. There were anti-immigrant popular initiatives during that period, aiming at limiting the number of foreigners in the country; in 1970 such an initiative gathered a 46 per cent ‘yes’ vote, with an exceptional participation rate of 75 per cent of Swiss citizens. Although more and more Muslims will be acquiring Swiss citizenship in the years to come, they do not yet represent more than one in ten Muslims in Switzerland at this point. Since Muslim immigration is recent (there were only 16,000 Muslims in the whole of Switzerland in 1970), most Muslims are still foreign citizens (primarily from the Balkans and Turkey). As in any other place in the world, the rapid growth of a foreign population gives rise to reactions, but especially so in the case of Islam, due to the often conflictual history of Islam’s relations with Western Europe.

• According to surveys conducted several months ago, a percentage of those who intended to support the initiative claimed to do it for reasons of reciprocity: they felt shocked by restrictions placed on Christian groups and other religious minorities in the Muslim world (for instance, the complete ban on non-Muslim worship in Saudi Arabia). Since the (sometimes quite difficult) situation of religious minorities in several Muslim countries is seen more and more as unacceptable at a time when religious freedom (including the freedom to change one’s religion) has become strongly cherished as a fundamental right, banning minarets is seen by some as a kind of retaliation for restrictions experienced by other religions in some Muslim countries (although we should add that it is difficult to understand how a ban on building minarets in Switzerland could improve the lot of Christians in Muslim areas; quite the contrary, in fact).

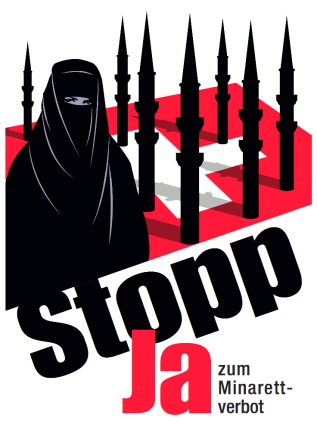

• Statements in the Swiss and international media emphasize the vote as signalling the progress of rightist, conservative, populist ideas and movements. While it is true that this is a part of the story, it is also an oversimplification, especially in light of the strength of the vote for banning minarets. One should not underestimate the share of voters sympathetic to women’s rights and women’s issues who would usually vote for political groups at the centre or on the left, but who feel that Islam does not give proper status to women (a perception that many Muslim women will obviously disagree with). It is significant that the controversial poster used by proponents of the ban during the campaign did not only show minarets growing like mushrooms on a Swiss flag, but also a burqa-clad silhouette. The status of women in Islamic law and practices, as well as distinctive signs such as the hijab (Islamic headscarf), create strong emotional reactions. If one attends any lecture on Islam for a general audience, questions on women and their status in Islam are quite likely to be asked.

• There is little doubt that a number of people who voted for the anti-minaret initiative did it not because of ideological beliefs or bad personal experiences, but because they have a bad image of Islam and Muslims, as reflected in the daily news, especially in the post-9/11 context (it is unlikely that the initiative would have gathered as many votes before 2001), for instance, in reports of suicide attacks, violence, expressions of hatred against the West, etc. Beside such international factors, a number of small, local problems have also contributed to reinforcing such suspicions and fears; for instance, only a few weeks before the vote, there was at least one reported (and documented) case of anti-Western preaching in a Swiss mosque. Although the media are increasingly careful to emphasize the distinction between ‘radical’ or violent Muslims, on the one hand, and average Muslims, on the other, the negative image conveyed by jihadism has an impact on people’s perceptions of all Muslims. Apparently, the Federal Government perceives this confusion as having played a key role in the initiative’s success.

• Some people – although it is unlikely this could have been a sufficient argument without being combined with other ones – were afraid that building minarets would sooner or later lead to calls to prayer from them, thus disturbing the public peace (in several places across Switzerland, the ringing of church bells has also experienced some limitations in recent years). Obviously, the argument that some day there would be calls to prayers from minarets was used by supporters of the ban to win voters to their cause.

• One should also not forget specific events in recent months that have contributed to anti-Muslim feelings and thus to the anti-minaret vote. Especially, one should mention here the current controversy between Switzerland and Libya. In July 2008, Hannibal Gaddafi, the son of Libya’s leader, was arrested by police in a five-star hotel in Geneva because he had assaulted two of the servants who had been travelling with him, leading hotel staff to report him to the police. Hannibal Gaddafi was jailed and then released on bail. The incident brought about a strong reaction from Colonel Gaddafi, and two Swiss businessmen who were in Libya at the time were denied permission to leave the country, a situation that has not been resolved to this day, despite extensive efforts by Swiss Federal Government members and diplomats. This ongoing situation has created a great deal of irritation among Swiss citizens, especially since Colonel Gaddafi obviously played a cat-and-mouse game with and ridiculed the Swiss government, among other things. Of course, anybody familiar with Libya’s recent history knows that the country is far from promoting conservative Islam and that the current Libyan regime has harshly repressed Islamist political groups (along with all other dissenting voices). However, such nuances escape the awareness of most people; what remains is the perception of a Muslim country humiliating Switzerland because it had enforced its commitment to protecting the human rights of weaker people (i.e. Hannibal Gaddafi’s servants).

• Finally, there are people – more numerous than one would believe – who simply feel that Islam is ‘foreign’ and does not really belong in Switzerland. While they have no problems with Muslims being here, Islam’s acquiring of visibility in public spaces creates reactions among those people, since it sends the message that Islam and Muslims are here to stay and will become a durable part of the Swiss environment. In an idealized Swiss landscape, there is simply no place for Islam, unless it is willing to remain invisible. Quite revealing in this regard is the short propaganda video posted in three languages on YouTube by the Federal Democratic Union in which an idyllic, peaceful Swiss landscape, with cows grazing in lush meadows and the powerful sound of the alpine horn in the background, is suddenly disturbed by a muezzin shouting in a strange language. Such a short, but powerful message strikes more of a chord than many observers would be willing to acknowledge. One of the leaders of the Federal Democratic Union told the present author: ‘Watch that video, it says everything!’

We could still add other elements to the list. For instance, at the end of one of the last political debates of the campaign on a French-speaking Swiss national television channel, pro-initiative politician Oskar Freysinger concluded by stating that he was concerned about the future of the West after hearing that the ECHR had recently approved a request by parents to remove crucifixes from school rooms in Italy, at the same time that Muslim symbols could freely penetrate European public spaces. No doubt this argument resonated with a number of viewers.

Ultimately, however, any attempt at making a listing of the motivations behind votes for banning minarets already reveals that the reasons for voting against minarets (and through this vote expressing suspicion of Islam more generally) are much more varied than some commentators would initially have us believe.

It would also be wrong to see the vote as a Swiss oddity. True, due to the system of popular initiatives, such feelings could express themselves in Switzerland in a way hardly conceivable in other European countries. On the other hand, however, there is no doubt that, should citizens in other European countries be given the opportunity to vote on such or similar issues, the outcome would be quite similar. While this may be hard for governments to accept, since they are fearful of the potential consequences, it is obvious that today in Europe a ‘Muslim question’ has been constructed at the intersection between religion and politics that takes various forms in various contexts. It may be unpleasant to acknowledge it, but whatever its justification or lack thereof, it is here and it is not going to disappear any time soon.

What now?

Swiss diplomats will be extremely busy in the days, weeks and months to come attempting to prevent over-reactions and to explain the intricacies of the case to other countries. Efforts will be directed not only toward governments, but also towards various non-govermental circles who might be willing to help in particular countries. One asset is Switzerland’s generally positive image in large parts of the world, and the fact that it is a neutral country, without a colonial legacy, and with no contingent of troops in any Muslim country – usually, people tend to associate Switzerland with institutions such as the Red Cross.

It is true that the anti-minaret vote could be used by groups in the Muslim world for their own purposes, although it is not definite that this will happen; while banning the building of new minarets will be seen as an hostile act against Islam and Muslims, it lacks the dimension of blasphemy, as was the case with the (in)famous Danish caricatures. Salafi groups even tend to see minarets as an innovation, since they did not exist at the time of the Prophet. All will now depend on the way in which the potential crisis is managed, and hopefully defused, but also on the willingness of specific actors to stir up (or not) agitation against Switzerland or ‘the West’ as a result of the anti-minaret vote.

In Switzerland itself, prior to this vote, controversies around Islam had usually not reached the same intensity as in some other countries. One should now expect a multiplication of tensions and small problems. Already, some proponents of the anti-minaret initiative have signalled their intention to continue with the forcing of public debates on issues such as forced marriages, excision and the burqa (or niqab – the burqa is the Afghan form of the full veil, which hardly anybody uses in Switzerland, and the niqab is mostly used by rich Gulf tourists coming for holidays in Switzerland). These issues have a potential to resonate widely, since most people in Switzerland would feel upset by such practices.

It is too early to know how Swiss Muslims themselves will react, after the initial shock and some easily understandable bitter comments about feeling rejected by – or at least unaccepted in – Swiss society. Few of them had expected such an outcome, and they had kept a relatively low profile during the campaign in order the avoid creating misunderstandings. There were open days in mosques, as well as participation in roundtables discussing the initiative, especially those organized by churches in order to convince people not to support the initiative. One should not forget that a majority of people listed as ‘Muslims’ in Switzerland (probably some 400,000 people now) do not attend mosques and do not belong to any Muslim organization – which is very similar to what can be observed in other Western European countries.

Leaders of Muslim organizations in Switzerland have called for calm, while obviously deploring the outcome. It remains to be seen which path they will now choose for presenting themselves publicly. If they choose to present themselves primarily as discriminated against and victims, it is unlikely that the situation will evolve; one should not forget that the people who voted against minarets did not do so out of a desire to oppress anybody, but because they are themselves feeling threatened by what they see as an Islam invasion. If Muslims confine themselves to complaining about ‘Islamophobia’, little will change and the situation will probably remain blocked. The most effective strategy would be to address clearly the various concerns that were listed earlier as contributing to the outcome of the vote. Let us now see if this will indeed take place.

In conclusion: back to history

It is always a good idea to keep the past in mind when analysing the present. In the current situation, for example, it is worth remembering that in the past there have been other controversies and conflictual situations centring around religious identities and representations in Swiss history.

During the 19th century, for example, there were decades of debates and tensions between modern state and liberal thinking, on the one hand, and the Catholic Church and political Catholicism, on the other, even leading to a short – and fortunately limited – civil war between Protestant and Catholic Swiss cantons in November 1847. More than a quarter of a century later, in 1874, the new Swiss Federal Constitution at the time introduced several articles targeting specifically Roman Catholics: for instance, the Jesuit religious order was banned in Switzerland; it was forbidden to create new monasteries or to re-establish older ones (only Catholics had monasteries in Switzerland at the time, just as today only Muslims have minarets); and new bishoprics could not be created without the permission of the Swiss Federal Government.

Many people no longer remember these events, but it took a whole century for these articles to be removed from the Constitution (although they were no longer enforced): it was only in 1973 that the first two articles were removed from the Swiss Federal Constitution. The interdiction on creating new bishoprics (a state intervention in internal Catholic affairs) lasted even longer: it was not removed from the Constitution until 2001! Thus, 19th-century religious controversies left a legal mark for more than a century!

In this regard, it is ironic that the paragraph of the Constitution where the ban on building minarets will now be inserted is the very same paragraph that applied until 2001 to the restrictions on the creation of new bishoprics ….

Nobody knows for how long the article banning minarets will remain part of the Swiss Federal Constitution. But it is useful to remember that similar issues have arisen in the past, before eventually being resolved. It is true that the issue of the Muslim presence in Switzerland is not entirely comparable with the situation of Roman Catholics in 19th-century Switzerland, primarily because Islam has come to the country only recently and mostly through immigration. However, looking back at cases from history shows us that the status of religious and non-religious groups in a given society is a result of negotiations, tensions and adjustments that are rarely resolved overnight – and even less so when the debate focuses on symbols.

Jean-François Mayer