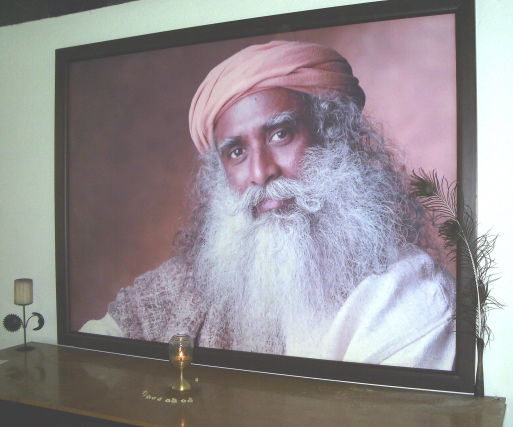

It’s only after I come out of the restaurant, after a breakfast of ‘roast dosa’ and filtered coffee, that I spot him in the adjoining newsvendor’s shop. He is on the cover of a Tamil magazine, an unruly grey beard that’s easily bigger than the glistening brown face it surrounds. He is the reason I have come to this industrial city of Coimbatore in southern India. Fifty-one year old Jaggi Vasudev, a.k.a. Sadhguru, founder of the Isha organisation and the ‘Inner Engineering’ technique.

But Balu, the news vendor, gives a lopsided smile when I ask if the guru is popular in this region. “People talk things about him,” Balu says.

What things?

A dismissive shrug.

I keep looking at him.

He relents. “When I asked some of my friends whether I should join Isha, they said, don’t.”

Why?

Just then Srinivas, the restaurant manager, walks up to us. He points to the pictures of Lord Shiva and Lord Venkateshwara behind the cashier’s desk. “When we have the real gods, why do we need gurus and godmen?”

Has he heard something negative about Sadhguru?

“Everyone has a weakness, Sir. Who is perfect?”

I tell him I have scoured the internet but didn’t find any of the scandal sometimes associated with gurus. Srinivas brings his hands together in a noncommittal namaste. “I hope you enjoyed your dosa. Please come again.”

Half an hour later I am in a bus hurtling towards Isha headquarters located at the foot of Velliangiri Hills some thirty kilometres away. Seated beside me is A.S. Ravi, who also needs to be goaded into talking. He took voluntary retirement from a Nairobi job and returned to India some years ago. Then he chanced upon a talk given by Sadhguru on TV. “That convinced me to do the introductory course. Now I am going for the four day course called Bhava Spandana. I will learn some more yogic practices. It will change my life much more.”

What changes?

Ravi gazes at the green hills in the distance, as if that’s where all the divine secrets are locked up. “How I can tread the spiritual path even as I perform day to day tasks. In the olden days, people struggled a lot for enlightenment. But Sadhguru has devised a way by which we can obtain it quickly.”

Although the term ‘Sadhguru’ means an unlettered guru, he’s actually a graduate in English literature from Mysore University. Perhaps he wants to proclaim that he is unlike any other guru. Or convey that it’s impossible even for an enlightened soul to know everything about the universe. Either way it’s novel marketing. But yes, he hated school and college. In one of his numerous lectures, he confessed that he disliked lecturers because most of them mouthed stuff that they didn’t understand or weren’t passionate about themselves.

“Isha Yoga Centre!” shouts the bus conductor. I look out of the window but there’s nothing, just the road forking, one goes left and the other plunges into thick vegetation. “We have to walk a kilometre,” says Ravi. “Or you want to take a taxi?” A couple of dusty Ambassadors are parked outside and their drivers look hungrily at us.

Let’s walk, I say.

It’s a good decision because the walk is invigorating. Tamarind and neem trees form a bountiful canopy overhead. The December air is so crisp it brings a pleasant ache in my lungs. Looming ahead, as if inviting touch, are the green hills of Velliangiri. Sadhguru has certainly picked a gorgeous spot for his campus. We walk past a guard whose posture suggests this place really doesn’t need any guarding, past plantations of coconut and areca trees fenced in by barbed wire. That’s when I notice two plain wires. Farther ahead my suspicion is confirmed: a symbol of an electric charge: the wires are electrified. I learn later that it is so only in the nights, to discourage wild animals like boar and elephants that roam these woods.

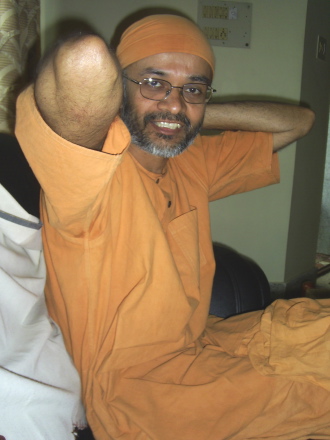

Soon we come to the actual centre, well spaced out buildings in red tiles and granite, several exquisite cottages and meditation halls, even an open-air canteen that’s busy frying vadas and blending fruit juices. All around men and women volunteers with ID tags move about briskly as if loaded with multiple deadlines. “Our organisation is young and lean,” said Nisarga, 39, a computer specialist from Indian Institute of Sciences and now a senior swami (celibate apostle) at Isha. I met him in Bangalore. “Sadhguru is always after us to get more and more things done. He stretches us to the maximum.”

On an elevated hallway, two giggling young women are lighting dozens of tiny snake-like lamps. I spot a few brahmacharis, male and female, walking with their heads down, with tags on their chests proclaiming “Silence”.

Ravi is taken away by a sari clad volunteer. And a brahmachari cloaked in saffron leads me to the meditation centre or Dhayanlingam. He says that I am in time for a special session. “From 11.50 to 12.10,” he intones solemnly and extends a hand. “Your cell phone and camera, please.”

I tell him I won’t take pictures or make a call. But the celibate just keeps looking at my bag until I surrender it. As I go towards the dome shaped hall, past a solid pillar that has Muslim, Christian and Hindu symbols inscribed on it, past large motifs of scenes from Hindu mythology, a young volunteer tiptoes to me and whispers, “Please fold up your trouser cuffs, they are scraping the floor.”

Moments later I step into the massive hall. The silence is deafening but what is more overwhelming is the tall lingam around which a massive snake has thrown seven coils. A metal cone at the ceiling drips holy water in widely spaced apart drops on to the lingam. The splats resound like occasional bullets. The half-raised head of the serpent seems to promise an awakening to those who seek. In fact that is Sadhguru’s proposition: meditation (combined with yogic exercises) to stimulate the seven chakras that are believed to reside in one’s body, the specific regions that will release the energy to experience the divinity lying dormant within each of us.

About fifty devotees squat on the cold floor, and all around, in grottos recessed into the wall, are thirty more, already meditating. The ceiling is a breathtaking hemisphere, thousands of bricks that seem to have jammed ineluctably. Not a single pillar anywhere. It’s evident that Sadhguru has drawn well and deep from his construction experience.

I spot a mat and dart there. But another volunteer urges me to sit elsewhere. Moments later, an attractive European or American woman attired in flowing whites steps on to the mat. She sits cross legged with practised ease. Two more people stride in, a young bearded man and an elderly plump woman. They sit near the lingam. They each pick up a porcelain bowl and with what looks like a stout pestle, move it on the bowl’s rim in circular motions. A metallic hum fills the hall and then the foreign lady starts to sing and sway. No words, just vocalisation of vowels. It sounds like a blend of the Occident and the Orient. I look around. The others are frozen, as if already transported to another dimension. The only other movement is near the door where a bearded man keeps tilting a long cylinder in which sand or some other powder gushes in a watery sound from one end to the other. I know I am expected to close my eyes but I keep looking around. I am no stranger to meditation and have experienced long states of serenity, together with reduced breathing and heartbeat rate.

“But this is much more,” says 38 year old Aloka, who I meet later in a residential building in the shape of a triangle, a shape that in yoga denotes stability and energy. “Sadhguru has locked into the Dhyanalingam the energies of the seven chakras or nadis that influence human life in several ways—earth, water, fire, air, space, knowledge, and divinity. It’s a permanent structure. Sadhguru believes his experience should be available for future generations long after his death.”

And yet I feel that Sadhguru has erred in calling the Dhyanalingam non-religious, that the lingam is not intended to represent Shiva, the destroyer aspect of the Hindu Triad, but is actually the optimal shape in science for preservation of energy. In terms of any communication in mass marketing, one of the fundamentals is that a message ought to be not only unambiguous but also perceived to be unambiguous. The lingam is universally acknowledged to be a Hindu symbol. It would be next to impossible to change that centuries old perception. Also the various props that adorn the walls and spaces of the Dhyanalingam hall—the engraved motifs from Hindu mythology, the serpent, the mud lamps—all are Hindu enough to deter people from other faiths to examine the supposedly non-religious nature of Isha. But I don’t want to start a debate with Aloka; my objective is to observe and report.

Hailing from Gobichettipalayam near Coimbatore, Aloka is a post graduate in electronics and worked with the premier Tata Consultancy Services. “I had certain beliefs about the West. I went to USA, saw what it was all like, the complete absence of the personal touch, the heavy leaning towards all things material. I didn’t like it. So I came back and was fortunate to have met Sadhguru in 1995.”

In 1996, Aloka became a teacher at Isha and in the following year he embraced sanyas to become Swami Aloka. “Isha has been in existence for the last 27 years and we have 15 sanyasis, all Indians, 12 males and 3 females, and approximately 130 brahmacharis and brahmachirnis. It’s tough to become one. For instance in 1996, there were 105 applications for the celibate life. Only five were approved by Sadhguru. The thing is you have to be ready. There’s a two year mandatory residence but you are allowed to visit your family occasionally. At the end of two years, if all goes well, if Sadhguru thinks you are ready, he will grant you permission to become a brahmachari. We also have fifty families from all over the world living with us in this campus.”

Why was it, I ask myself, that Sadhguru, a married man, wanted his closest disciples to embrace celibacy? (His wife, Vijayalakshmi, passed away in 1997—“She attained samadhi,” Aloka said. “She worked in a bank in Mysore but gave it up when Sadhguru summoned her. She was like a mother to us. She still remains a channel for us to Sadhguru.” Their daughter, Radhe, is in Chennai, studying performing arts.)

It was only after sifting through the numerous speeches, both written and recorded, that I found out what could be the reason. Sadhguru believes that complete enlightenment is possible if that is the only focus in life. Perhaps what is unsaid is that Sadhguru, who has a reputation for being clinical in his methods, direct in his attitude, and no-nonsense in his talk, demands utter loyalty so that his movement spreads in the specific way he wants.

“We know that corruption and undesirable attitudes can crop up in our organisation,” Nisarga had said. “But Sadhguru is determined to keep such negative stuff away. He wants the movement to remain as pure as possible.” Maybe that’s one explanation why the movement claims a following of a quarter million which is modest when compared to, say, that of Amma Bhagwan (the Oneness Organisation) which claims several million. It could also be one reason why it was difficult for me to get views of outsiders in Bangalore and Coimbatore on Sadhguru or the Isha movement; nobody seemed to know much about either.

But the bubbling and attractive Kumud, who took me around the campus (150 acres), gave me an interesting perspective. A film producer in Mumbai and the youngest of seven siblings, Kumud has been residing here for the last two months as a volunteer. “I did the basic course last February, I wish I had done it long back.”

What made her do it?

“I was grappling with some important questions. What is my life all about? Where am I headed?”

Where was she headed?

“I want to become a brahmacharini,” she said simply.

Looking at her glowing face, her colourful kurti and pyjamas, her well toned personality, I couldn’t help but express surprise. I ask her the question that is commonly asked in India: Why didn’t she want to get married?

“Isha makes more sense to me.”

So when will she become a brahmachirini?

“Depends on Sadhguru. He will know.”

How many times has she met him?

“It’s not necessary to meet him. He is always here. He knows me.”

At the time of my visit, Sadhguru was away in Delhi. Sadhguru travels frequently, lecturing international institutions and conferences. In brochures supplied by the organisation, I learnt that he is a member of the World Council of Religious Leaders, Alliance for a New Humanity, and was a delegate to the United Nations Millennium Peace Summit, Australian Leadership Retreat and Future Summit, the Tallberg Forum in Sweden, and the World Economic Forum in Davos.

The brochures also quoted S.V. Parthasarathy, Executive Director, Ashok Leyland Finances Ltd, who says: “After the practice, I am able to give the same kind of output at 5 pm that I am able to give at 9 am.” And a psychiatrist, Jim Broom, of Sewanee, TN- USA, puts a scientific stamp on the programme: “It gives a clear step by step methodology that leads one to a new understanding and way of being. Negative self-defeating patterns simply drop away.”

Yet, Deanie of Massachussets, an art teacher and mother of two adopted children, shared a somewhat guarded perspective on the Isha movement. I met her at the canteen. This was her second visit to the centre, she said; she is teaching at the home school for the last four months. “I was looking for a teacher, a guru, when a friend of mine, who had visited the Nashville centre of Isha, asked me to try this programme. I met Sadhguru briefly in 2002. I am still in the process of committing myself. Yet I am involved in a slight way to bring the Isha movement to the Boston area.”

Deanie is a petite woman in her sixties and has only recently undergone a divorce. “After 25 years of living with the man, he decides to quit!” she sighed. The pain is evident in her voice. Then she changes the subject. “I suppose it’s easy for the younger generation to catch fire, to try out something new. For older people like me it takes some time. But again, one cannot generalise. All people are different.”

What did she like about Isha?

“Well, I have found some yogic practices that have stuck to me. I am a churchgoer actually, yet I found the Isha programme attractive. I am no longer depressed. My general health and concentration levels have improved. I can exercise my emotion at will. From agitation to equanimity. I also feel more courageous than I really am!” She finds Sadhguru’s logic perfect and there is a clear magnetism about him. “I especially like meditating at the Dhyanalingam. It has a gravitational aura about it, something bottomless and strong.” She finds the people at Isha impersonal; they mind their own business, “but there’s a common denominator, something about this place on a social level that binds us all together. Especially when we sit on mats on the floor to eat or meditate.” She feels it would be incredible if world leaders go through the programme but is convinced that won’t happen anytime soon. “They are caught up in their own belief systems. Why will they trade that for this? They won’t change the status quo because it means forsaking huge amounts of money and power.”

When I prepare to leave, Aloka bundles up some literature authored by Sadhguru (Encounter the Enlightened published by Wisdom Tree proved to be a stimulating read) and some prasadam and hands them over to me. “You must come again, experience more of this place,” he says. I am thinking of it.

Ramesh Avadhani

The story behind Isha’s birth

Nisarga was one of the earliest to become a Swami at Isha. He had this to say about Sadhguru’s background. “He was a rebel, always questioning what was normally accepted by society. For example, as a boy when he was dragged into a temple he asked of his parents: why was it necessary to pray before idols? What good would it do? He would get beaten up for that. In ten years he changed ten schools in and around Shimoga where he was born. It was also because his father, an ophthalmologist with the Railways, was shunted him from place to place. When the time came to join college, Sadhguru refused. Instead he spent a whole year reading all kinds of books. Finally, because of parental pressures, he enrolled for the B.A. course and just about managed enough examination questions to pass.”

After college, Sadhguru wanted to make a lot of money because he craved to travel the world. He started poultry farming as that was a thriving business in those days. He succeeded, and his father was thrilled. But Sadhguru disappointed him by winding up the farm. “He was bored of chickens,” Nisarga chuckled.

Sadhguru then teamed up with a partner to enter the construction business in Mysore. It did very well. Once again his father was thrilled. And once again he was in store for disappointment. “One afternoon,” Nisarga explained, “while sitting on a rock on nearby Chamundi Hills, Sadhguru experienced something mysterious yet ecstatic. He was left crying and smiling for several hours.”

From then on the experience repeated frequently. It endowed him with a deep insight into life and people, an insight that proved to be an unfair advantage over competitors in the construction business. He wound up the business and set about finding what exactly it was that he had experienced. “In the ensuing months, he was able to remember experiences in a previous life with a sage called Palaniswamy.”

A previous life?

“Yes, about three hundred years ago. And there are many people in Isha who experience vivid memories of their past lives. It comes spontaneously. It can come to you too. Only you need to prepare yourself for it through appropriate yogic techniques. As the Sadhguru says, the body and the mind both die but memories remain forever.”

Sadhguru was already equipped with various aspects of yoga learnt during his youth from Malladihalli Swamy, a reputed yogi in Karnataka. This knowledge together with memories of life with Palaniswamy helped Sadhguru design specific practices for the yoga of gnana (intelligence), bhakti (emotions), karma (action), and kriya (energy). This method of ‘inner engineering’ that Sadhguru designed was to align these four ‘wheels’ in such a way that one could travel smoothly. “Each individual is equipped with different strengths in each of the four qualities,” said Nisarga. “In one, the head is dominant, in another the heart, and so on. So, for each individual, only a specific blend of the four can work to bring the desired results. Sadhguru’s mission was to share all that he knew with the rest of humanity. That’s why Isha Yoga Centre. Isha means the formless divine. Which is why our movement is not religious but spiritual. Anyone can join us.”

He said that there are a variety of yoga programmes costing between $ 5 and $ 20 in India (free of cost in villages). A minimum transformation is guaranteed even with the entry level programme. “For many people, the minimum transformation can prove to be life turning.” The basic course is over five days, three hours daily. It comprises the shambhavi maha mudra or inner engineering. “Certain heightened states of peace and joy can be experienced.” The next is bhava spandana, a four day residential programme. “It’s a deeply inclusive experience that gives you a glimpse of what is possible to change your life.” Then there is a two day residential programme where a set of asanas of the Hatha and Kriya disciplines are taught. “This is to clean the nadis in your body to channel the divine energy latent in your body.” The Shoonya meditation is also a two day residential programme that offers deeper states of awareness. “Most meditation programmes use the mind. Here you break free from that.” Finally there is the seven day Samyama residential programme that is observed in complete silence. “You meditate for 14 to 16 hours everyday, to explore the maximum possibilities of your consciousness.” — R.A.

For more details: isha.sadhguru.org

© 2008 Ramesh Avadhani