Sometime in March this year, a young man went around dropping pamphlets in verandas and porticos of my neighbourhood in Bangalore. I thought it was a sales promotion by a shopping mall or a new restaurant but no, this pamphlet talked of something else: the inauguration of a mammoth temple in marble that took seven years to build. Constructed by the Oneness organisation in the neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh, the temple boasted of the largest pillar-less meditation hall in Asia–able to accommodate 8000 people. Moreover, the temple was supposed to be endowed with spiritual powers of ancient rishis who had meditated in the region. On entering the temple, the pamphlet declared that

“the cowardly become courageous, the unwise become intelligent, barren hearts start flowering in love, and everyone will experience divinity”.

Flowery language, I thought, but interesting, considering that all those attributes are in short supply these days. But who were the people behind the temple? I searched the text but found nothing. Just a line stating Sri Amma-Bhagwan Sharanam (the sacred feet of Amma-Bhagwan) and three telephone numbers.

I called up the numbers and eventually met Dr Chowti, a consultant physician with Bangalore’s well known Mallya Hospital. A slim and earnest man in his fifties, Chowti invited me for the inauguration and also gave some literature about the Oneness organisation. The literature showed excellent pictures of the temple, Bhagwan and his consort, Amma, ecstatic devotees, and quotes of some celebrities.

For instance, Donna Karan, the renowned fashion designer, wrote: “The Oneness Blessing gives us the opportunity to connect to that which we long for our Higher Self, giving us the ability to experience peace and guidance and to fulfil our life’s purpose, which is to share love and compassion.” Another one, from NR Mohanty, former chairman of India’s premier aeronautical establishment, HAL, said: “Sri Amma and Sri Bhagwan’s divine love and blessings have awakened love and joy in my family. They made me realise the value of relationships in life. I no longer worry about the past or the future. I am no longer afraid of facing challenges in life.” Certainly not original words but I was intrigued; anyone who claimed to instil love and compassion in people merited a closer look.

Dr Chowti said that over a hundred thousand devotees from India and abroad were expected to arrive for the week long inauguration ceremonies beginning April 22; I could visit on April 25. But on April 23, he called up to say that the ceremonies were postponed indefinitely because more than half a million people had landed on the first day itself. “It was totally unexpected. We had some problems,” he said.

The Hindu carried a report the following day: “A stampede occurred when devotees, in the absence of any proper facility for drinking water, pushed and jostled in frenzy at a water point. In the resultant melee, many persons were pushed and trampled upon, leaving five persons dead and more than 100 injured.”

Police investigations and bad publicity naturally followed. Quite an inauspicious start, I thought, for a temple that was to usher in ‘the dawn of the golden age’.

Although the temple remains closed as of now for the general public, I managed a visit there in early July 2008. My motives were just two-to examine whether the structure came up to all the superlatives that the Oneness organisation used in its literature and website (www.onenessuniversity.org), and two, to get some impressions of the leader duo.

The Journey

The Oneness Temple is located about 70 kilometres from Tirupati, itself a region of more than a dozen popular temples; the world famous Venkateshwara temple atop the nearby Tirumala Hills is the richest in India. I went to Tirupati, five hours by road from Bangalore, and boarded a bus for Kalahasti, some 30 kilometres away. Seated next to me was Dr V Venkataratnam, a retired professor of English. I asked him about Amma-Bhagwan. The professor said that he had not personally met the couple but had seen them on TV. “A lot of people believe in them. As far as I know no one in this region talks ill of them. Bhagwan appears to possess some mystical power which some people find hard to understand. His ideology sounds good but I don’t know if it’s working in practice.”

From Kalahasti, I took another bus to Varadaiahpalem and hired an auto rickshaw for the remaining half an hour’s journey to Bathalavallam where the temple is located. The rickshaw was already crammed with seven or eight people. I had some trouble communicating with them-they spoke only Telugu, the regional language, of which I only knew a smattering. So, my questions were left dangling in the air, half intelligent and sparsely worded. But Sadiq Basha, a lean scruffy man of about twenty five, came to my rescue. He spoke in Hindi, a language I knew well. He said that about a hundred Muslims live in Varadaiahpalem and all of them had visited the temple as it promoted equality of all religions.

So, what did he think of the temple?

“Oh, we just went, saw, and came back,” he said a bit abruptly, and it was only later I realised that he had given such an answer because he assumed I was indirectly asking him whether he believed in Amma-Bhagwan. “But it’s an excellent temple,” he added with grudging admiration.

I asked if the economy in the region had improved after the Oneness people had begun their activities here (the organisation has adopted 120 villages in the area for social welfare and also has six campuses-the Oneness university-spread over 400 acres to teach their philosophy through various courses). Either he didn’t understand the question or didn’t know the answer. He merely shrugged his shoulders and we were silent thereafter, just watching the flat scrubby land rush past.

Minutes later, inch by marble inch, the temple came into view to the left of the road. Even though the morning light was hazy, the magnificence of the structure was unquestionable. As I took in the sight, I wondered why the temple was built in such a remote place. Could it be simply a question of strategy? Because, when you think about it, it’s evident that the more difficult it is to reach a place of worship, the more value it automatically adds on to itself.

But Prasad, one of the elite group of dasas or guides of the Oneness organisation, gave me another reason. “Prabhat Podar of Ramanashri Ashram in Pondicherry, is a well known architect. He also measures ground energy and possesses some mystical powers. He came with sophisticated instruments and found unbelievable amounts of energy in this place. According to Bhagwan, that energy helps in elevating our consciousness, to experience the divine in all his splendour.” He went on to say that Podar was initially not a believer of the Oneness philosophy but when he saw this place and experienced a face to face meeting with Amma-Bhagwan, he became an ardent devotee. Podar sketched a rough layout of the temple within twenty minutes and Bhagwan finalised the blueprint with just a few changes to facilitate an atmosphere of unity and harmony. Prasad stressed that those are the key elements of the Oneness temple. “If a Christian comes here, he would experience Christ. A Buddhist sees Buddha. And a Muslim senses Allah. That is the uniqueness we have achieved.”

The Temple

Certainly the setting was unique-wide open land embellished with shrubs and trees, the misty hills of the Eastern Ghats on the horizon, and this marble monolith designed in a blend of Buddhist and Hindu styles, complete with stupas (topes), spires, domes, ornate doors and latticed windows. But two things I felt missing were the tall minarets and steeples commonly associated with mosques and churches. Also, one of the entrances had the word ‘Om’ inscribed in several languages. That was undoubtedly a Hindu slant. Prasad clarified that Bibles and Korans were available for Christians and Muslims. That, to me, seemed an inadequate effort to propagate unity of all religions. The unity ought to be distinctly palpable in every aspect of the temple (although the latticed windows and parapets pointed to Islamic architecture).

Prasad said that the Amma-Bhagwan couple was right now at their ashram in Neham, near Chennai, but that I could view them on a DVD of the inauguration proceedings. We sat in the reception room and watched the video and I must confess that I hadn’t seen anything like it: thousands of people, Indians and foreigners, sitting with joyful expressions, waving their hands and swaying their bodies, hanging on to every word that the Bhagwan was talking.

The man was unquestionably handsome and had a regal air about him. His voice had this riveting bass quality- deep and strong. He spoke fluently in English and Telugu and later on his wife, Amma, a radiant woman decked in a cream and gold silk sari, continued the sermon, promising the gathering untold joy in terms of self realisation and experience of the divinity.

I asked Prasad how long he’d been associated with the movement.

“Twelve years. I am one of the 150 dasas that Amma-Bhagwan chose for propagating the Oneness philosophy.”

The group of dasas is now called Team 150, because the organisation believes that success in any large scale endeavour is quickly achieved with a core group of 150 people. Their endeavour is certainly grand-“to enlighten 64,000 people to a state of extremely high consciousness who will in turn enlighten the rest of humanity”. I was reminded of an Indian fable where a rather amused king attempts to grant the inventor of the chess game, an impoverished man, his simple wish-a grain of rice in the first square of the chessboard, two grains of rice in the next, four in the third and so on, each time the amount increasing by a square of the preceding number. But in no time the king turns desperate, not all the rice in the kingdom, nay even the whole country, is sufficient to complete the 64 squares! Perhaps, I mused, 64,000 enlightened disciples would indeed have such an exponential effect on the rest of humanity.

I asked Prasad how far the Oneness organisation had travelled towards this goal of 64,000.

“We have a few thousand enlightened disciples or sevaks now, but by the end of 2012, which is our deadline, we will have 64,000.”

Suppose it wasn’t achieved by that year?

“I personally feel we can do it,” Prasad said with an indulgent smile. “But a little delay is all right.”

Prasad is from Vijayawada and is just 30 years old, although the patchy stubble of grey hair on his shaved head lends him an elderly look. He has this likeable quality about him, a mellow manner of speech and gentle gestures. He looked like a man at peace with the world. Not once did he show the slightest irritation when I posed some tough questions to him. But I will talk about that later.

We went around the temple. Prasad said that the original cost was estimated in the region of $ 15 million but it escalated to $ 75 million by the time construction was completed. As we climbed the stairs, a few labourers were polishing and trimming the marble. When I touched a banister, my hand came away coated with marble powder. “Some work remains to be done,” said Prasad. “Once we open the temple, all of us have this conviction that the crowd of devotees will rival that of Sri Venkateshwara’s temple on Tirumala Hill.”

That was quite a claim since Venkateshwara’s temple enjoyed the numero-uno status for Hindus: to gain a darshan of the sanctum sanctorum, one has to stand in a queue for at least ten hours. (Of course, rich devotees can do it quicker, depending on the money they fork out for special tickets!)

The Oneness temple site is spread over 42 acres with the actual temple occupying five acres. Thick walls and solid carvings lent the temple a fortress like appearance. The ground floor is a massive waiting hall. The second floor an intermittent resting place called the Artha Kama or the temple of desires and solving problems, and seeing the numerous pillars all about the hall, it somehow seemed appropriately named. I could imagine people pondering over their internal conflicts before making the final journey to the top floor, the pillar-less hall or the Dharma Mokhsha where shrines of Amma-Bhagwan are kept (I didn’t get to see them; they were covered with a tarpaulin). “We aim to also keep a golden orb once we open the temple,” said Prasad. The orb, he said, will reflect each devotee’s individual faith in some way or the other.

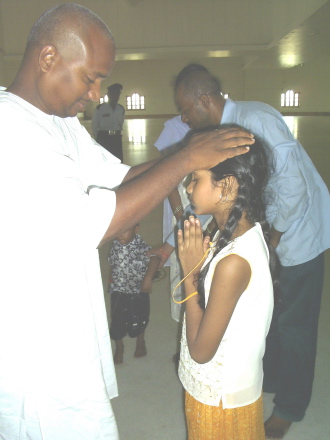

The walls had built in windows of lattice work and the doors were plated with what looked like a copper alloy with beautiful carvings of gods and goddesses from Hindu mythology. The floor at the entrance was inlaid with a beautiful rangoli pattern. Several reminders, I thought, that this was a place of worship and some reverence was expected. Just then a gaggle of special invitees streamed in and Prasad spoke to them amiably. He then placed his hands on each one of them for a minute or so. It was the act of giving deeksha, a healing power that enlightened disciples are believed to possess.

I talked to Rambav and Yugandhar, two middle-aged men from the group. Rambav is in the grocery business in Ponnur town of Guntur district and Yugandhar is into embroidery work from the same place. Both men have been disciples of Amma-Bhagwan since 1996. “They have helped us in each and every way,” said Rambav. “All that we have achieved in life we owe it to them.” When I asked him to elaborate, he ticked off the achievements on his fingers: inner guidance, mental relief, matrimonial harmony, good business, and fine children. “Fresh problems do occur as time goes by, that’s life isn’t it?” he went on. “But they get solved faster” He also spoke of being childless after marriage but “on meeting Bhagwan, he asked me what kind of a child I wanted. I said a child that would be inclined to become a scientist. My child was born on the same birthday as Thomas Edison!”

Later, as I strolled out on the wide balcony and gazed at the sylvan surroundings, I recalled what I had so far found out about Amma-Bhagwan and the controversies that followed them over the years.

Amma-Bhagwan

Though there is nothing available on the Oneness websites and literature about the origins of Amma-Bhagwan, there’s plentiful information, some clearly posted by troubled minds, on the internet. One article, titled “A White Paper on Kalki Bhagwan” by Dr Vasudha Narayan of the University of Florida, traces the birth of Bhagwan as Vijay Kumar on March 7, 1950 or ’51, in Arcot district of Tamil Nadu. He schooled in Madras (Don Bosco’s, according to another website) and worked until 1987 (according to another website, as a clerk in the Life Insurance Corporation of India and also as a rice vendor in a Chennai suburb). In the intervening years, he married Padmavathi Devi. The couple has one son, Srinivasa, who supervised the actual building of the Oneness temple.

Around 1988, Vijay Kumar met Paramacharya Sankara Bhagavatpada (also known as Guruji), a doctorate in nuclear engineering from Germany, who was deeply influenced by the philosophy of J. Krishnamurti. What is not clear is how the roles reversed–Vijay Kumar became the guru and Sankara his ardent disciple! Sankara went about spreading Vijay Kumar’s by now enlightened views, largely culled from the teachings of J Krishnamurti, Bhagvad Gita and Buddhism. The movement grew under various names-the Golden Age Foundation, Bhagavad Dharma, Kalki Dharma, and now the Oneness Organisation, and Vijay Kumar himself took on one title after another-Mukteshwar, Kalki Bhagwan, and now simply as Sri Bhagwan. (In the ’90s, disciples saw Vijay Kumar as Kalki, the tenth incarnation of the protector aspect of the Hindu Trinity, Lord Vishnu, but apparently, Bhagwan is increasingly reluctant to use that title now as it doesn’t go down well with a wary public.)

I asked Prasad about a report in India Today (July 10, 1997) where Bhagwan was accused by some residents of Chennai of detaining their children forcefully to groom them into monks. “That’s an old issue that was resolved. A few teenagers had second thoughts about their commitment. Even now, we monks or dasas are free to leave if we want to. No one is under any compulsion. Suppose I want to get married tomorrow, I can leave.”

Did he want to get married?

Prasad shook his head emphatically. “The joy I get here in helping hundreds and thousands of people is immeasurable. I doubt I can get so much joy as a husband or a father.”

What about the accusation that Bhagwan charmed influential people, made use of them, and discarded them afterwards?

A small furrow appeared on Prasad’s brow. “I am not sure that is correct. Yes, Bhagwan does like to befriend influential people in all strata of society-movie stars, politicians, industrialists and so on. But that is because he wants our movement to spread quickly. These powerful people can convince others to join the Oneness movement. I don’t see anything wrong in that. About discarding people, that is not correct. People have continued to remain with us, supporting all our activities.”

Some posters on a website dismissed Bhagwan’s teachings as nothing but putting old wine in a new bottle, that Christ, Krishna, Buddha and many saints had already talked ad nauseam about love, compassion, selflessness and so on. What did Prasad have to say about this?

“See, people want to love, but are unable to do so. They need a facilitator, a helping hand. Amma-Bhagwan provide that helping hand. You cannot change by yourself. It’s almost impossible to eliminate what you have learned in the womb, what you have accumulated in your formative years. But here at the Oneness organisation, we can help you bring about the change. The basic thing is to accept who you are, what you are. Then the change will happen. We help you open up your unconscious mind which is about twenty thousand times more powerful than the conscious mind.” He talked of several courses that the Oneness organisation has for this purpose: Elite Processes, Youth Deeksha and Maha Deeksha, each one with different levels of teaching lasting from three to seven days.

It’s surprising, I told him, that an organization that boasts of a hundred million followers all over the world did not do much to counter all the above accusations.

“Actually, none of us dasas have experience in interacting with the media. But now, I think it’s time we did something about it. We need to counter all the accusations and bad propaganda. We are planning to engage a public relations firm in Chennai and also purchase our own TV channel. That should help us a lot. We should have thought of these things long ago.”

Prasad added that writers and journalists should attend at least the basic course at the Oneness University and judge whether the experience was beneficial or not. “What about you?” he asked, “surely you can come for a programme next month?”

No, I said, I have some other assignments, but accepted his offer to drop me at the temple gates. After bidding him goodbye, I crossed the highway and stood there, waiting for a bus or a rickshaw. And then I had second thoughts-perhaps I should indeed make time to attend their basic course, find out more about the Oneness philosophy, and see for myself whether it was a practical way of life or not. I liked what Prasad said about the dasas having inadequate skills to handle the media. It sounded honest.

Ramesh Avadhani

© 2008 Ramesh Avadhani. All rights reserved.