Under the dynamic leadership of Prof. Dr. S. N. Balagangadhara (Ghent University, Belgium), the organizers have engaged in an exploration of the following issues, as they explained in the conference material:

– Is it possible to say that the descriptions of Indian culture and its traditions are the products of the Western experience of India?

– In the domain of religious studies, in post-colonial studies and in the field of comparative science of cultures, scholars have begun to argue that the questions and conceptual framework for the study of India and its religions are firmly embedded within the Western cultural history, i.e. within the theological framework of Christianity. How true is this?

– If this is true, what are the possible alternatives?

In order to understand what is at stake, Religioscope conducted an interview with one of the participants at the conference, Dr. Martin Fárek.

For additional information and material on the conference, see:

http://www.rethinkingreligion.org/

Martin Fárek is a researcher from the Czech Republic, and is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Studies and Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy at the University of Pardubice, a town situated one hour’s drive east of Prague. “I found the university to be developing in a very dynamic and open way, which was very appealing to me,” he explains as his reasons for working there.

Dr. Fárek is involved in research on several issues, all of them connected more or less with India. One of them is the representation of the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition in the writings of Anglo-Saxon intellectuals since the 19th century. His second field of interest is the new routes taken by Indian traditions in a Western environment and how they are transmitted in the modern era, especially after the Second World War. Dr. Fárek has also written a book on problems and processes of institutionalization in ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Counsciouness, also known as the Hare Krishna movement). He has examined the interpretations of the works of Ram Mohan Roy, one of the great reformers of the 19th century. He has also dealt with debates regarding the issue of Aryan invasion theory.

Moreover, Dr. Fárek, who also teaches Sanskrit, has a special interest in the Puranic material.

Religioscope – India is a country that fascinates many people in the West. Was your original interest in India also linked to this fascination?

Fárek – It was certainly not through tourism! It started in my childhood. One of our Indologists, Vladimír Miltner, wrote a series of stories based on Ramayana, Mahabharata. He put those into very short stories about Krishna, Rama and Sita, but there was also a story about Buddha, and the seventeenth century hero Shivaji. They were all published as a book for older children (from aged 10 onwards); I liked that beautiful book so much! I was 10 or 11 years old at the time, and I read it several times. The attraction is also a thing of the heart. India and all things Indian proved to be a very strong attraction for me – I cannot tell precisely why.

I slowly started to meet people belonging to several groups that are connected to India. My older brother was also interested in yoga and meditation practices. Together with my interest in the Sanskrit language, this is what brought me to my area of study.

Religioscope – Very often, a fascination for India goes along with stereotypes in the West. Quite early in your research, you would have certainly been confronted with such issues.

Fárek – Yes. When I started my research on Western descriptions of the Chaitanya Vaishnava tradition, especially Anglo-Saxon descriptions, but also those from some German and other sources as well, I found that several things were unsatisfactory. I knew the tradition from my own travels in India and from the Sanskrit sources and translated Bengali texts that I had read. I felt that the picture that was presented didn’t fit at all with that tradition. Here you have Western people saying: “Look, this tradition is a part of Hinduism,” but the same people did not understand the basic philosophical and intellectual claims of the Chaitanya Vaishnava tradition, which is also a school of Vedanta that attempted to reach a synthesis of discussions around the teachings of Ramanuja (1017-1137, according to tradition) and Madhva (1238-1317). But most Westerners’ work just didn’t fit in with what I knew.

Then I also started to see problems with the idea of the caste system, because it also affected one’s understanding of the tradition itself, as well as the question of the position of women, and also the understanding of texts that didn’t fit into the framework of many Western scholars. This even included the understanding of bhakti practices themselves, how they were described, and what they were meant to be. Western scholars sometimes missed things that were important for people within the tradition that I had studied; in fact, some of these things were entirely missing in Western descriptions.

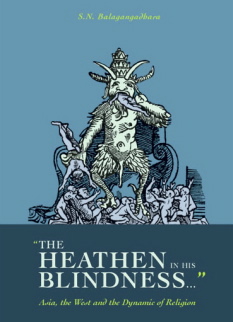

All this together made me think about the reasons why such things are happening. Four years later, I came across the work of Prof. Dr. S. N. Balagangadhara (Ghent University, Belgium), after having met his students at a conference, as happens in the academic world. We had an interesting discussion, which showed me that they were actually working within a broader theoretical framework, but very much along the lines of my own thinking. Balagangadhara’s work “The Heathen in His Blindness”: Asia, the West and the Dynamic of Religion clarified some questions for me, and especially helped me to see more clearly how our Western understanding still sticks to the Christian theological framework. The conclusions I had already arrived at fitted in very much with this picture: some of the basic claims and structures in the Western understanding of India were shaped by missionaries and Christian thinkers in general.

Religioscope – Did you also come across such stereotypes and misunderstandings in the work of secular authors? How far did you identify the ideological presuppositions that drove such views?

Fárek – There is a double movement under way. What I have found in the secularized approach developing in that area of studies especially after the Second World War (and it is not a coincidence that this process could only have happened after the fall of the British Empire and the shift of much scholarship to the United States) is that quite a few scholars developed views according to which a concept such as “Hinduism” was very vague and should not be applied. They were able to put aside some of the simplistic notions about the caste system, and they also showed that the Gaudiya Vaishnava communities were working at very different levels in their understanding of social norms.

Field research, such as the work by Charles Brooks, Hare Krishnas in India (Princeton University Press, 1989), which I found inspiring, or the research of Prof. Joseph T. O’Connell (University of Toronto), who has a long acquaintance with the tradition, has an understanding of several languages, and has undertaken long-term observation of festivals and rituals, came to conclusions that more or less departed from the earlier presuppositions.

But on the other hand, there are many people still using the “classical”, philological-erudite assumptions and structures in their descriptions of the tradition. You have many remnants of the old structure of constructed Hinduism, or even the old structure in its entirety, still being applied by several authors. Other authors, however, have been able to distance themselves from those presuppositions and to reach new insights.

Religioscope – So the turning point was the fall of the British Empire?

Fárek – According to the material I have seen, it started in the 1960s. Several works appeared that took into account the importance of sound within the tradition, for instance. The singing of the name of Krishna, with an Indian and specific Chaitanya Vaishnava understanding of the sound, could be described as sonic theology (this term was used by Guy Beck in his work), although the word “theology” is used here with a meaning different from the Western one. Other scholars took seriously insiders’ views on human spiritual growth and accomplishement as such, which were taken as more important than social position, family lineage, etc.

Religioscope – And what happened with the tradition you have focused on would obviously also apply to other Indian traditions.

Fárek – I suppose so. At least till the 1920s, you would more or less have found very similar descriptions and structures, patterned on Christian (and especially British Protestant) theological notions. They tended to obscure the tradition rather than than helping people to understand it better.

Religioscope – If we can summarize, from a postion where we have been projecting Western approaches onto an understanding of India, we have come to approach India on its own terms.

Fárek – It seems to me that at least some people were able to bring about a shift in that direction. They managed to access the tradition from inside, at least in a small way.

Religioscope – And we now come to that intriguing idea of “rethinking religion in India”. For most people outside India, the country is seen as a place where religion is prospering, pervading everything. How does it come about that both Western and Indian scholars feel the need to “rethink” religion in India? What is at stake here?

Fárek – Many basic questions have arisen about understanding differences between cultures, how different cultures meet, how they describe each other and in which terms, and also whether the people from the various cultures can be helped to really understand each other better.

For India in particular, this process is very much connected with the discussions on Orientalism started by the famous book by Edward Said, but especially by the application of Said’s observations on India by Ronald Inden in his book Imagining India. Prof. Balagangadhara, the organizer of the conference that took place in New Delhi in January 2008, wrote the abovementioned book, The Heathen in His Blindness, which was first published in the 1990s. We have here also Richard King, who wrote a lot about Orientalism, and Timothy Fitzgerald, and other scholars who are more or less aware that the descriptions of India by Europeans were in many ways problematic.

The basic question is: What is the definition and role of religion? Christianity is probably the best exemple of religion as we know it in the West. While the conference was focused on India, it is very much connected with the general discussion about the definition of religion itself. Prof. Balagangadhara has demonstrated extremely well that we have either inconsistent definitions of religion, or scholars remain more or less silent on the issue of such a definition after many unsatisfactory attempts at achieving it. Some other people have put working definitions forward that really work only for their particular field of study. In general, the situation in the discipline that calls itself “religious studies” is theoretically and methodologically not very satisfactory. Implicitly, the question at stake is also: “What do we study?”

Religioscope – But when people speak about Hinduism, what is problematic?

Fárek – It also depends on the position of the person speaking about Hinduism. When a Westerner speaks about Hinduism, I see several problems. One of them is the notion that it is a unified religion. There have been so many different attempts to define Hinduism itself; I myself have written an article about these discussions and definitions. Some people say that the term “Hinduism” makes no sense. In academia, you have radically diverse opinions on the very basic understanding of what Hinduism is.

Behind this, there are more serious questions. When we speak about Hinduism in Europe, in our classrooms or in the media, we are conveying to people the idea that a religion such as Hinduism exists and that this is what Indians are. By doing this, we are explaining what the people of India are, what they do, why they do it, etc. We make sense of Indian cultures and traditions according to this definition of Hinduism, very much connecting it to the caste system and a range of other issues that have arisen at the conference.

The question is: Does all this really help us to understand people in India?

Let’s now turn to India. Several Indian participants at the conference have done a wonderful job of showing that this understanding of “Hinduism” is more or less the product of interactions between European and Indian people, and is thus also a part of the colonial legacy and the question of what colonial rule had to do with Western perceptions of India. It is during those interactions that the notion of “Hinduism” emerged. But the basic tenets of this construct called Hinduism are older – they are rooted in Christian theology and have been repeated in Western desriptions of other cultures for centuries.

Of course, there are people who suggest that the term “Hindu” itself is much older (well known in this regard is David Lorenzen). Interestingly enough, a colleague from Japan mentioned that expressions such as “Hindu Dharma” can be found in 16th century Chaitanya Vaishnava texts. But if you study the material carefully, you see that these descripitions arose from the long-term interaction with Muslims. For me, it is no wonder that, after years of Muslim rule in Bengal, people came to use the foreign (but already several-hundred-year-old) term to talk about Hindus. But when you come to the process of Indian communities’ self-description in situations like ritual or philosophical discussions, you will find that the term “bhakta” is used (which is loosely translated as devotee, or somebody who has submitted to the deity), or the term “Vaishnava” (one who is devoted to Vishnu), etc. The existence of the word “Hindu” at that time does not prove that it was used to describe a religious community.

This leads us back to the question of the conference. Balagangadhara feels that we are replacing the entire experience of people in India with something different.

Religioscope – But we know that, in history, no religion is frozen in time or concepts! Any religion also evolves and develops through interaction with other worlds.

Fárek – You have to ask: Development of what sort? Of course, you have Christians interacting with the Roman Empire, where one finds different cults, and the Greek philosophers – many actors were involved. In the case of Christianity, despite the persecutions Christians endured, the development was more or less a voluntary one. What happened in India was not that voluntary at first. When you come in particular to the emergence of a Hindu identity and later of a unified Hinduism, which becomes an ideological movement like Hindutva [Hindu nationalism] in modern India, you see how this creates an alienating experience for local people.

Despite the fact that it has a very strong Christian bias, many Indians finally accepted this process: I think this was originally very much connected to colonial projects in the field of education. And in its turn, this colonial project was much connected with Christian missionary zeal, which can be summed up as follows: “Be like us! Be like us Britons!” This is a very different process. It is not that you are changing something only slightly here and there, and if you like you can adopt this prayer or these practices (which many Indians did, by the way: many Indians just put Jesus next to Ganesha, Shiva and others!). It shows very clearly that here we have the meeting of two very different cultures and traditions, with very different understandings of themselves and of the world.

If you study everything that the missionaries did, they were very influential in building a project later adopted by the East India Company’s rule, and also by the government after the fight for Independece [1857]. Things that people such as William Ward [1769-1823, a Baptist missionary] or Alexander Duff [1806-78, a Christian missionary and educator] were just dreaming of: education, restructuring the whole society, remoulding the local law (both “Hindu” and Islamic) in order to make it fit with the ways of the British – this all shows that there was a deliberate effort from the European side to replace one kind of experience, tradition, practice and understanding with another quite different one.

Religioscope – It is interesting to observe today in several parts of the world – including in the Muslim world – currents claiming that the mind should be decolonized. Can we say that what has taken place at the conference “Rethinking Religion in India” is part of those trends toward decolonizing the mind? Is there not a kind of ideological agenda as well?

Fárek – I would not say that the agenda is ideological: but it is about ideas, surely – about the ideas that shape our understanding. In that sense, we are trying possibly not merely to decolonize, but to “detheologize” our minds, not on the personal level of forgetting that one is a Christian or whatever, but on the level of how that theological understanding shaped our constructions of India.

Religioscope – Do you expect such an undertaking to have any impact outside of academic research? Do you see it as something more than an intellectual exercise – something that could initiate changes in Indian society?

Fárek – I think it can. But there is a question of several layers or groups when one is speaking about Indian society. At the conference in question, during several sessions and discussions, one could observe that there are people whom we call “Hindus” who rarely use the word, and if they did, it was because they had to complete forms for the government or respond to census questions such as : Are you Christian, Hindu, etc., i.e. What is your religion? It was on these occasions that many Indians first heard about “Hinduism”! Many of them decided: “OK, I am Hindu!” But this obviously did not mean much to them. So we must think first of all about how many people in India still live in villages – I think possibly 70 per cent of the population. These people are not touched by these emerging notions of “Hinduism” so much and whatever other terms are used. Of course, then you have the educated strata of society, not only intellectuals: I think they are the real targets of the conference – the educated so-called “Hindus”. Many of them experience difficuty in understanding who they are and what their tradition is. Some of them feel that they are anglicized or modernized, but what are the alternatives? There is a lot of heated discussion around such questions. This is a sign that this conference can achieve a more general outcome.

Religioscope – Such an endeavour, however, is bound to clash with several “camps”. It puts into question the whole ideology of Hindutva, but also the approaches of liberal academics…

Fárek – It is very thought-provoking and provocative, right!…

Religioscope – …and it is also very much a minority position.

Fárek – I would think so. I do not think that many people would share the opinions of the scholars present at the conference – both Indian and Western. But for me, this in itself is an exciting thing. It has much to do with the core issues at stake – if we are to improve our understanding and perhaps help Indian people in some way to understand why some problems appeared in their lives, and the lives of their predecessors.

There was a wonderful exemple in one of the sessions of the conference, presented by a group of academics doing research at the University of Kuvempu (Karnataka) on issues related to the caste system and untouchability. Difficult issues today! There are several communities who suffer in India today, including communities in very good standing in one part of India who are oppressed in other parts of the country. The paper about untouchability was wonderful in many ways, and in one way it showed that you cannot solve untouchability in India as a problem without dealing with the broader issues that arose at the conference. The researcher presenting the paper, who himself had occasionally had very painful experiences with regard to untouchability, told us: “You see, untouchability has nothing to do with religion, with Hinduism. There is something else behind it. And what I say after doing a great deal of research” – i.e. these were not statements just based on his personal experience, even though he had actually thought originally that untouchability had something to do with religion – “is that at least in Karnataka, religion does not fit into the picture.” He said that, at the moment, the government of India is more or less approaching the problem of untouchability as a religious problem, and since India is a secular state, the government will never interfere with it. There are laws demanding equality for all citizens, but this is not the solution to the problem of oppression. He said that, in some areas, because of this secular approach, the problem of oppression of some groups by other groups is getting worse. We do need to rethink the whole idea of the caste system, but this problem is very much connected to the notion of “Hinduism” and how the structures of Hinduism are perceived. We have first to deal with this issue, because it is blocking our search for possible solutions to the problem.

I found that very important, as one particular example of what we are talking about here.

Religioscope – We can see that this definitely has implications far beyond academic discussions…

Fárek – In this case, this standpoint is applied to policy. People may start to look at this problem as one of different groups, classes and communities, or a problem of traditional behaviour in certain ways, or maybe one of the ownership of resources. It is as if you are presented with an unchangeable fait accompli: OK, it is a religious problem; so secularism will solve it. India has a whole system of rules and laws, but then apparently, after sixty years of independence, the problem has not been solved…

Religioscope – Today, in India, and this is the irony, we could say there are Hindus, because there are indeed people who really perceive themselves as Hindus, and there are people who continue to practise their religion according to the traditions of India. Nevertheless, we see that part of the population really has integrated that perception, and has become “Hindu”!

Fárek – Yes, but I think the problem is that we see all of them as Hindus, including those who could never make sense of what the word “Hindu” means. Of course, due to the reform movements, many people in India see it differently. If you study, for example, Brahmo Samaj, you will see how it found a particular identity: Ram Mohan Roy and others basically accepted the Christian Unitarian framework, and the subsequent struggles and divisions of the movement must be understood from this fact, although Brahmo Samaj is often seen as an attempt to reform Hinduism. There is an irony here, because Brahmo Samaj ended up, from a legal perspective, as a sort of separate religion in India. They wanted to celebrate marriages and enjoy the protection of the law for their families, so eventually there was a special Brahmo Marriage Act in colonial India (1872), because other people didn’t see it as traditional practice.

There was also another important thing, raised by Sharada Sugirtharajah (Dept. of Theology and Religion, University of Birmingham) in one of her comments: there are discussions about and accounts of how converts to Christianity make sense of their own experience. She pointed to a case where somebody – an Indian convert – was describing to his fellow Western Christians his experiences with regard to Jesus and to prayer, and they were horrified: they said that it was impossible – that it was not Christian. We see here an instance of a meeting between two traditions and two ways of experiencing…

In a sense, the conference “Rehinking Religion in India” was also about acknowledging radical otherness. One of the important things that Prof. Balagangadhara has contributed is the notion that, through the process of describing other traditions as religions (Hinduism, Daoism, Shintoism, Confucianism, Animism…), we Westerners have actually only replicated ourselves; i.e. the process is one of creating just another “us”.

This is why I speak of “radical otherness”: it is not just somebody else that we are talking about, but somebody very different. This is what I feel to be very important about meetings like this one: some participants are already aware of such issues, and we must somehow try to open the doors more and find out what this radical otherness looks like. Because we may not really be meeting other people and other cultures, even though we think that we are…

The interview took place in New Delhi and was conducted by Jean-François Mayer.