Moscow, April 6, 2007 (RFE/RL) — Since coming to power, the Russian president has not tried to conceal his Orthodox faith. But, according to some, he was not always religious. Father Igor Vyzhanov, a spokesman for the department of external church relations at the Moscow Patriarchate, says Putin’s views on religion have changed.

“I heard about a miracle with a small cross which he had experienced, and according to which he started believing,” Vyzhanov says. “As for the fact that the president goes to church at Easter, I think this is his personal matter, too.”

Aleksandr Verkhovsky, the director of the Sova Information and Analysis Center, which monitors religious discrimination in Russia, says the president is undoubtedly a fervent believer.

“Frankly speaking, I don’t see any dynamics [indicating his faith is becoming more intense]. On the contrary, I think it is less than during the first two years of his presidency. Then, it was really noticeable,” Verkhovsky says.

“But at some point I think he was forced, or he took the decision, to distance himself a little from the church leadership. Because everyone had the impression that he was a man interested in the church, and the church leadership hoped that this would mean they would have very close relations. But, in fact, no one intended to propose close relationships, because that was not something the government needed.”

Separation Of Church And State

The Russian Constitution asserts that the church and the state must be entirely separate. Traditionally, Russia has had four official religions — Russian Orthodoxy, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism. But there are fears that Putin’s obvious Orthodox faith means he favors one religion over the others.

This week, the Russian government announced it would hand back land that was seized from the Russian Orthodox church after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

Aleksei Malashenko, an expert in religious affairs at the Carnegie Moscow Center, says the Orthodox Church isn’t likely to become Russia’s only official religion.

“But at the same time, we have to recognize that the Russian Orthodox Church occupies a special position, and it has special relations with [the] state, and their ambitions are mostly political ambitions. They want to participate in the elaboration of the Russian way of development,” Malashenko says.

A recent example of this was the decision made by schools in several regions of the country to introduce compulsory courses on Orthodox Christian culture.

In response, the Council of Muftis of Russia raised its concerns about the growing influence of the Russian Orthodox Church, and announced it would pressure the government to expand the instruction of Muslim culture beyond the Muslim republics in the North Caucasus to other regions with large Muslim communities.

Orthodox in name

The Sova Center’s Verkhovsky says there are two reasons the Russian Orthodox Church seems to have priority over other faiths in Russia.

“Firstly, it’s connected to the traditions of the Russian statehood, which perceives itself, roughly speaking, as the heir to the Principality of Moscow and the Russian Empire, and not as an amalgam of the multicultured citizens that make up Russia today,” Verkhovsky says.

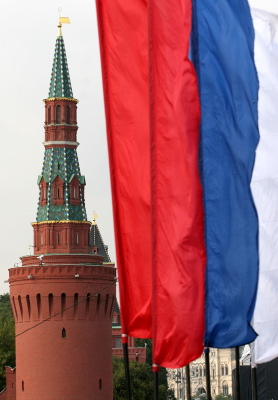

Officially church and state are separate in Russia Officially church and state are separate in Russia “On the other hand, the Orthodox faith is, to some degree anyway, the religion of the majority of our citizens who called themselves Orthodox, even though they don’t entirely know what this means. Some don’t even believe in God, but they call themselves Orthodox Christians, and so the church indirectly speaks for them.”

But Father Yakov Krotov, a religious commentator, is more skeptical. He believes the government and the president give preferentiality to the Orthodox Church over other faiths.

“Putin has shown he is a believer, an Orthodox Christian, but when it comes to politics, he is a politician. That’s to say that he doesn’t support the Orthodox Church as a whole, he supports those Orthodox believers who were brought up by the Kremlin nomenclature over the past 60 years,” Krotov says.

“He doesn’t even support the Orthodox faith in particular, he supports those aspects that are part of the religious elite. That’s to say he suppresses one group of Muslims, and supports another, he suppresses one group of Jews and supports another. It’s an old Soviet trick: selection. It’s a similar thing to what Hitler did.”

But Father Vyzhanov doesn’t see anything as sinister in Putin’s faith: “As for the fact that the president goes to church at Easter, I think this is his personal matter, too. For example, when the president of the United States shows his religiosity, or points out to his church his confession, no one sees any problem in this. The presidents are human beings, too.”

There has been speculation that Putin’s recent trip to the Vatican, to meet Pope Benedict XVI, might pave the way for an unprecedented meeting between the leaders of the Russian Orthodox and Roman Catholic faiths — an indication, Vyzhanov says, that Putin welcomes and supports all denominations.

© 2007. RFE/RL, Inc. Reprinted with the permission of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 1201 Connecticut Ave., N.W. Washington DC 20036.

Website: http://www.rferl.org/