Luanda, 13 Dec 2006 (IRIN/PLUSNEWS) — A three-year old HIV-positive child, who was also suffering from malaria, was accused by neighbours of using witchcraft to kill his parents and abandoned in a coop, where scavenging chickens pecked him, blinding him in one eye.

Other villagers, hearing of his plight, rescued him and turned for help to Rev Horácio Caballero, of the Arnaldo Janssen Centre in the capital, Luanda, but the toddler died while the paperwork was being completed for him to receive medical treatment in Spain.

Reports of children accused of witchcraft are common in parts of northern Angola: between 2001 and 2005, 423 children accused of witchcraft sought refuge at the Santa Child Centre run by the Catholic Church in M’banza Congo, the capital of Zaire Province, on the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), while others fled their accusers, only to end up on the streets of Luanda.

In terms of Angolan law, street children, orphans or abandoned children, are to be reintegrated into their families or, in the case of orphans, placed with their relatives. But when it comes to allegations of witchcraft, the situation is complicated by stigma, which can lead to outright refusal by family members to care for the child.

Recognising the problem of children tainted by allegations of witchcraft, Caballero uses healers to perform symbolic purification rituals in the presence of family members, who are then able to witness the child being ‘liberated’ from being possessed by witchcraft. Once the ‘evil spirits’ have been removed, the child can safely return to the family and the larger community.

Children accused of being possessed by spirits are sometimes taken to the centre by relatives, or left by the more timid under a large tree at the entrance, while other abandoned children are picked up on the streets by volunteer workers.

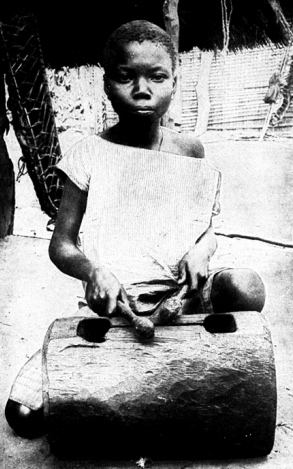

Caballero said the children were often “traumatised by the conflict of separation and rejection, with cuts, burns and others wounds – marks of torture beyond measure – because it is believed that abusing the body expels the bad spirits“. They have nightmares and wake up frightened. He added, “They need a lot of love just to feel safe.”

The process of stabilising a child emotionally takes about two years, during which the family is located and social or religious workers investigate both the desire and preparedness of the extended family to accept the child’s return.

“We hear the two sides, we discuss things, and together we arrive at a conclusion,” said Caballero. “If the child and the family accept it, we call a traditional doctor trusted by the family, who organises a ritual to expel the witchcraft.”

The centre reunites about 260 children with their families every year, of whom about 60 percent, nearly all from the Bakongo tribe, have been accused of witchcraft.

For some, the trauma and the bad memories get in the way of reuniting with their families. They remain in the Janssen Center, secure but isolated.

“The problem is that these children are going to grow up outside a community, and the context of community is necessary in Africa”, said Filomena Andrade, director of the Christian Children’s Fund in Angola.

A recent study by the National Children’s Institute (INAC), the government’s child protection department, and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has called for a policy to help rehabilitate children accused of practising witchcraft.

This article comes via IRIN (Integrated Regional Information Networks), a UN humanitarian information unit, but may not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its agencies.

© UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs 2006