Jane Williams-Hogan is a sociologist of religion. She got her degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1985 doing a dissertation on the formation and development of the Swedenborgian Church in England. She is a professor at Bryn Athyn College of the New Church and has taught there for thirty years. She is also the Carpenter Chair of Church History and has been working in Swedenborg’s studies for the last twenty years. She has recently published a book in Italian on Swedenborg and the Swedenborgian Churches: Swedenborg e le Chiese swedenborgiane (Leumann [Torino]: Editrice Elledici, 2004, 136 p.), which is a volume without any equivalent for providing an overview of the Swedenborgian movement in its different branches worldwide.

Religioscope – Swedenborg is a name that has been known to people interested in literature and in spirituality, or who are familiar with individuals such as Helen Keller. But could you please explain to those people who have never heard about Swedenborg who he was and what was his contribution to religious thought?

Jane Williams-Hogan – Emanuel Swedenborg was born in Sweden in 1688 and he was the son of a Lutheran bishop. He graduated from the University of Uppsala in 1709 and thought he was interested in being a scientist. After graduating, he went off to Europe to explore all the marvellous, new scientific discoveries and technological developments that he could not have seen first hand in Sweden. He returned to Sweden in 1715, where he spent the next ten years attempting to find a position for himself in Sweden. In 1724 he was appointed as an Assessor to the Board of Mines. His family had been in mining and it was in many ways a very logical position for him.

He then spent another ten years working on a book that he published in 1734 in three volumes, called the Philosophical and Mineralogical Works. It included a first volume titled The Principia, in which he discussed cosmological issues; the other two volumes focused on iron and copper, both important metals found in Sweden. In my opinion, his Principia details his attempt to understand the nature of God, the Creator; in addition he wrestled with the problem of creation. He developed the concept of the first natural point, to account for the finition of the infinite. His cosmological system proceeded from that first finite point.

Immediately after the publication of his cosmology, he wrote a very small work called The Infinite and Final Cause of Creation. The intellectual problem he attempted to resolve in this work was simply that: if there were no difference between the human and the mineral worlds, then, in fact, everything he had written in the Principia explaining the nature and operation of minerals would likewise explain the nature of the human. He determined, however, that “the human” was the final cause or essential purpose of creation. In other words, that human life was what had been intended by God to be the fulfilment of creation. Swedenborg determined this because he observed that only human beings were able to return to God all the qualities which had come from God; they could do this because they could not only receive these things, but they could respond to them either affirmatively or negatively, indicating the capacity to freely response to the Creator.

With that realization, he decided to focus his energies on looking for the seat of the soul in the human body. He worked on that problem for close to eight years; and he attempted to resolve it in two separate efforts. To accomplish this, he did a tremendous amount of work in the areas of anatomy and physiology. In the process, he developed a systematic philosophical methodology. His philosophical methodology was helpful to him as he tried to penetrate deeper and deeper into understanding the living human organism in an effort to try to grasp the mechanism that animated it.

It is my understanding that, at this time, he had mechanistic concepts about human development, because he really felt that he could use scientific and philosophical tools to find the soul. He wrote a book called The Economy of the Soul’s Kingdom. He published it. Dissatisfied with his effort, he re-present his ideas in another work The Soul’s Kingdom. It is my opinion that in these efforts, Swedenborg was seeking to know and understand God the Redeemer.

One of the things I always found intriguing about this particular endeavour of Swedenborg’s is the fact that, at one point, he starts his examination of the human body with an exploration of the blood and pulmonary system. I found it interesting because, I don’t think most people’s first way to dive into the human body would be through the blood. A lot of people might start with the mind, or the brain. Other people might start with the heart. But the interesting thing about Swedenborg’s focus on the blood is, that it is the blood that receives everything that comes from outside of the human body, and which then meets everything that comes from within the body. It is in the blood where all the nutrients and the oxygen that comes from outside meet the various hormones and the blood cells that are manufactured in the body. Thinking about the blood as the meeting ground suggests, to me, some of the things Swedenborg was looking for in terms of trying to comprehend human life. Living human beings are not self-sustaining, he was seeking that spark of life that come from without—the soul. He got very frustrated as he was writing this book—the more he searched nature, the more elusive was his goal. He left Sweden to publish it because it was not possible for him to publish in Sweden due to the censorship of the Lutheran Church.

Religioscope – And then comes a turning point in Swedenborg’s life…

Jane Williams-Hogan – Yes. On his trip to Holland to publish his work, The Soul’s Kingdom, he began to have strange dreams. He began to record these dreams. Prior to this, he had had, what I would call, psychic experiences in which he would see lights in his mind. From his point of view, these lights would guide him. They would tell him to start or to stop different kinds of thought processes and so on. On this trip in 1743, he began to write down these dreams. Initially he just listed dreams or gave titles to them. His very first dream was: “I dreamt of my youth”. I am currently writing a biography on Swedenborg and find that intriguing because, when Swedenborg became a revelator, he reports that God flows into people through their sweet good affections stored deep within them particularly during their infancy and childhood. According to Swedenborg, God uses these affections in our adult life, if we let Him, to call us to reform and to grow spiritually. So for Swedenborg to return in his dreams to his youth reawakened innocent spiritual connections.

The dreams began in earnest in March of 1744. He recorded several dreams a night and in the process of these experiences, he began to see who he was in reality. The man he saw did not look very good. One of the things, I find interesting is that, as far as I can tell, Swedenborg probably looked like a very proper and upright person; but underneath that properness, that uprightness, and his incredible work ethic, was someone who was extremely proud and very arrogant. He was someone who seemed to cherish his intellectual superiority, rather than desiring to develop more sensitive or loving relationships with other people.

He recorded these dream experiences over a period of about eight month. Each night when he would dream, after waking he would write them down and then he would interpret them. So one of the things I find fascinating about Swedenborg is that he is one of the very first dream interpreters in the western world, preceding Freud by over one hundred years. Dream experts who understand the symbolism of dreams feel that Swedenborg’s interpretations fit very nicely within modern frameworks of dream interpretation. During this period, he was really struggling with who he was, what his aim was, what his love was, and what his task in life might be. It should be realized that while he was recording his dreams, he was also working with a printer to publish his multi-volume book on The Soul’s Kingdom.

Religioscope – But you previously mentioned that this was a process that would lead him to become a revelator. What did happen?

Jane Williams-Hogan – At the point at which he was having these dreams, he was in his early fifties. During this dream period he comes to believe that he came face to face with the Lord Jesus Christ. He recorded this experience in his dream journal. He also came to feel and believe that he was being called to do some kind of important work, but he did not know what it was nor the form it would take. He completed the work he went to Amsterdam to publish, while at the same time he records going through severe temptations for about six to eight months. He comes out of this period a changed and chastened man. By the time he stops recording his dreams and temptations, and has published the last volume of his Soul’s Kingdom, he wrote a small book called The Worship and Love of God. He published the first two parts of it in 1745. He never completed the third part, which stops in mid-sentence. The poem is a recreation of his philosophy and is a hymn of praise to God. It can be seen as a gift to God, who had led him through the “wilderness” of his own soul until he found a garden.

He had been in Europe during this period of time. He returned to Sweden not knowing exactly what path he would take. Nonetheless, he continues to work as an Assessor on the Board of Mines. He writes a small work called The Messiah about to Come, which is a series of biblical passages, which are from the prophets, primarily. You could say he was identifying with the prophetic call and was beginning to see his call through the calls, the terminology, and the thoughts of these other prophets. There is some question as to whether or not he already knew Hebrew, which I personally feel he did. At this time, he also began to study the Bible in Hebrew.

As he’s reading the Bible he did two things. He wrote a little manuscript, which is called The History of Creation according to Moses, in which he began to interpret the first chapter of Genesis – it is only about forty paragraphs long. Swedenborg wrote everything in paragraphs and numbered them, which was a very common practice at that time among European intellectuals.

He also began to write a Bible index, which he started by looking at the prophets again. One of the things I think is interesting to reflect on here, is that the language of prophecy is very colourful. When he was trying to figure out what these words in the Bible mean or, using Swedenborg’s terminology, corresponded to, he had a very rich language to deal with in the prophets. This richness no doubt added to his ability to develop correspondences. Eventually he turned to Genesis to explore its deeper meaning. At the same time, he continued to do Bible interpretation. In the process he wrote an eight-volume work that he never published, called The Adversaria or The Word Explained. In that work, he attempted to explain natural creation. In order to do so, he used correspondences. He dug more deeply into the Bible to explain the creation of the world. In The Worship and Love of God, he has explained the creation of the world; in The History of Creation According to Moses, and in this work, The Word Explained, he was attempting to explain the creation of the world.

And then, two things happened. There exists in his Bible index an entry having to do with the correspondence of the Garden of Eden. There is a notation that “garden” means regeneration or re-creation. At this point, Swedenborg began to see that the story in Genesis was not really a story about the natural creation of the world at all; but as he ultimately came to understand it, it is the story of the creation of the human being, who is born into the world, loving himself (dark and without form and void) and needs to become a living garden—to love others and to love God. The seven days of creation detail the process through which this transformation takes place. The first hint of this is the entry in the Bible index, written perhaps in 1747.

During this period of time he also was writing another book, which is also a notebook in which he recorded his experiences in the spiritual world. He began recording these visions several years after he had put aside his dream journal. These visions took place, according to his own testimony, while he was reading the Bible or, what he called, the Word of God. He made notations of these visionary experiences on a fairly regular basis in his journal, unpublished in his lifetime, but now called either the Spiritual Diary or Spiritual Experiences. At one point in his diary he wrote that he had had a vision of the spiritual kingdom as a whole. From my point of view, that vision of “the whole” signalled the possibility that he was now able write a book that could explain the nature of spirit or “heaven,” and the nature of man or “earth,” as Swedenborg would say.

At the same time he was writing these manuscripts attempting to interpret the Bible, he continued to work as an Assessor. He resigned his commission in 1747, just after he was elected President of the Board. The message of this new revelation is that there is one God, and that G

od is the Lord Jesus Christ. Swedenborg claimed that this is God’s final revelation not only for the people of this earth but for the entire universe. This was so, according to Swedenborg, because what happens in one place in the universe has an impact in the rest of the universe. God came down on our earth, at a certain point in human history, to put in order the spiritual environment of the human mind—a spiritual environment that had become so dark with falsity and evil that people could no longer see or feel God’s presence, and thus, could not freely follow him.

In Swedenborgian terms, the fall or the expulsion from the garden in Genesis really refers to the fact that human beings, instead of being willing to be led by God, who is love and wisdom itself, wanted to follow their own hearts and judge things from their own perception or minds. Heart and mind among the first inhabitants of our earth were united—what they loved they thought and what they thought they love. Over time, as their loves focused more and more on their own ways apart from God’s ways, and because they were unable to raise their minds above their own natural loves, they turned more and more to evil and falsity. As people began to love their perceptions more than the teaching they had from God, they moved farther and farther away from God. They chose to love themselves and the world more than they loved God, thus they were “ashamed” to be in God’s presence in his garden.

A judgment took place, not on Adam and Eve as actual people, but on, what Swedenborg called, the most ancient church. After the collapse or end of this church, human beings were now able to elevate their minds higher than their affections so that they could in fact again be able to be led to God, to heaven, and to a good life. Swedenborg defines a good life as a life of use or service to other people, and thus to God. The Church of Noah was established at this point. Swedenborg refers to this as the ancient church that in time also became corrupt.

At the end of that church, God instituted the Jewish or Israelitish Church which was, from Swedenborg’s point of view, a completely correspondential church. This means that it was a church that ritually had to do exact right actions in order to be in a right relationship with God. According to Swedenborg, those right actions, required of the Jewish people, contained an internal meaning that corresponded to spiritual truths. Those right actions prescribing what to wear, how to pray, how to construct the tabernacle, how to sacrifice and the myriad of other details found in the Old Testament actually corresponded to spiritual truths that teach us about how to order our minds to receive God, and how to order our lives so that we can be of genuine service to other people.

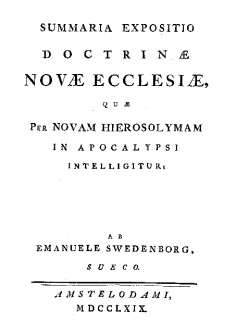

So Swedenborg’s first revelatory work, Heavenly Secrets, published anonymously in eight volumes from 1749-1756, opens the internal or spiritual sense of Genesis and Exodus. It provides an extensive explanation about the process through which the Lord Jesus Christ came on earth, his combats with evil while he was here on earth in order to subjugate the hells, and his victory over them.

Now, why did he want to subjugate the hells by coming on earth? He came on earth so that he would preserve the freedom and individuality of the people who had chosen not to follow him, or to live good lives during their time on earth. Because God’s essence is love, he did not want them to be annihilated, but he did want them to be put in order in such a way that they would no longer be able to impede the spiritual freedom of subsequent generations. Evil spirits believed that because God was in the flesh that they in fact could not only tempt him, but that they could successfully tempt him. They believed that they actually could control him. So God came on earth, engaged in spiritual combat with the hells, and through his crucifixion, which was his final temptation, he allows himself to die for the sake of his resurrection. He wanted to demonstrate to people, the reality of spiritual life, and the fact that even if you are born of the flesh, if you are born natural, you can, in fact, overcome temptation and achieve eternal spiritual life.

Swedenborg has written a book I didn’t mention previously, called The Last Judgement (1758). Swedenborg felt that, just as the previous churches had become corrupt and had fallen, the Christian Church also became corrupt and fell. According to Swedenborg, the corruption of the Christian Church stemmed from the worship of three persons, instead of one God, in whom there is a trine of soul (father), body (son), and spirit (holy spirit); and in the separation of faith and charity, or faith and service to other people. The Protestant churches, particularly Lutheranism, taught salvation by faith alone; and the Catholic Church believed that a person could be saved through the works of the Church, that is by taking communion, and not by the quality of life that a person had lived. The emphasis was not necessarily on doing good neighbourly service to other people, but on following the edicts of the Church. The judgment of the Christian Church in the spiritual world permitted, the light of heaven to flow into human minds, providing them with freedom in spiritual things. So that is a little bit of his theology.

Swedenborg published his last work True Christian Religion in 1771. In it he wrote: “Now it is permitted to enter intellectually into the mysteries of faith.” Swedenborg asserted that the great spiritual mysteries of human life could at last be rationally explored, because their inner order has been revealed. At the same time that these new truths were being brought to earth, Swedenborg wrote that a New Christian Church was being born in the spiritual world. In Swedenborg’s teachings, since the spiritual world is the world of causes, and the earth is the world of effect, what happens in the heavens effects what happens on earth. With the birth of the New Church, if you will, in the spiritual dimension, human beings could now be spiritually free to really wrestle with the issues of their life, the issues of their faith. They would be able to really investigate the fundamental question of human existence, and be able to seek to know God’s ways, not out of mere obedience, but through an understanding of the process whereby one can, in fact, subordinate one’s love of self to a love of God and to a love of other people. Swedenborg teaches that God’s love and wisdom helps people to reorder their minds, and to reorder their affections in such a way that they then can be of service to other people.

This then is a very different theology than the theology of the Christian churches. In addition, Swedenborg did not feel that you had to have been a Christian to achieve salvation. He did believe that people everywhere who live a good life according to principles of religion that are outside of themselves could, in fact, achieve salvation. So you do not have to become a member of this New Church in a specific sense, to receive salvation. You may, in Swedenborg’s terminology, be a member of this New Church in a more universal sense. Since the publication of these works and the completion of Swedenborg’s mission here and in the heavens, there have been a huge number of people that were able to choose to live a good life, as a result of the life giving freedom that has come into the world. Swedenborg in revealing the nature of heaven and hell to the world through his books has now open up spiritual things to human beings. So while one can imagine heaven and hell in a place that is beyond this world, Swedenborg also clearly teaches that that place, beyond this world, is really your own mind. We create a heaven or a hell within us as we live our lives, and after death, what we have created becomes our eternal home.

Religioscope – Even if one

did not need to become a member of a specific group called the New Church in order to achieve salvation, did Swedenborg create a group in order to support and propagate the doctrines he revealed?

Jane Williams-Hogan – Swedenborg died in 1772. There were probably at that time four or five people who had read his works and felt that they were true. He never attempted to found a church and he never preached. He only wrote these books. It is fascinating that, in spite the fact he only wrote these books, by the year 1800 the books had literally been carried all over the world and had influenced large numbers of people.

When he died, there were a few people following his teachings in Sweden, who were persecuted by the Lutheran Church, and who were not allowed to teach theology once they had come to accept Swedenborg’s new Christianity. In addition, there were a couple of people in England who translated some of Swedenborg’s works into English. There was also a Frenchman by the name of Pernety who translated some of his works into French; and not long after that translations were made from the French into Russian and taken into Russia in the 1780’s. Swedenborg’s books were brought to the Americas in 1784, and they were sent to Australia in 1788. They were brought to West Africa before 1790. So it is possible to picture that these books are sort of sailing all over the world; and at every point along the way, they are affecting a few people, but this was certainly not a mass movement; and is not even today.

In England there were groups of readers. One group was begun by a man with the name, Robert Hindmarsh. He had a Methodist background. He read Swedenborg in 1782 and, he decided that what Swedenborg had to say was true. He put an advertisement in the papers and probably made handbills: as a result five men came together in a coffeehouse in London and those men ultimately formed what was the start of a group called the Theosophical Society (not to be confused with the unrelated group bearing the same name and created in 1875). At its height it had maybe a hundred members and had people from all walk of life in England, shopkeepers, aristocrats, doctors, physicians and a lot of foreigners – so French people, Polish people, Swedish people, as well as English people were involved in this Theosophical Society. What they did was to read and discuss, as well as publish Swedenborg’s writings.

In the north of England there was a fellow by the name of John Clowes, who had come across Swedenborg’s writings in the early 1770s. He had had a very dramatic experience in his life related to them. He believed he was actually called to return home to read a book that he had ordered, but had just put aside. While on a fortnight visit with friends, he had such strong visions of the few words he had read, Divine Human, that he rushed home to read Swedenborg’s Arcana Coelestia. An Anglican cleric with an independent position, he became a shepherd to groups reading Swedenborg in Lancashire region of England. He also translated Swedenborg’s writings into English, and was a member of a Manchester printing society that distributed them.

So, in the 1780s, in England there were people trying to see what the next step might be. Robert Hindmarsh, resident in London, ultimately was interested in establishing a New Church organization that was separate from the previous Christian churches, because he felt that it was difficult to worship the one God, the Lord Jesus Christ, in churches where they still talked about the trinity of persons. Swedenborg wrote about a trinity but it is a trinity of soul, body, and spirit (mind or active life force); this is like the trinity that exists in every human person.

So under Hindmarsh’s leadership, in 1787, they established a group, which a number of months later, established a priesthood. So you had a group formed in order to set up New Church worship; and then about six to ten months later, they established a mechanism whereby they instituted a priesthood for the Church. To determine who would officiate at the ordination, the men present drew straws, feeling that the Lord’s providence would guide them. Robert Hindmarsh drew the straw, permitting him to officiate. Hindmarsh’s father, James, a former Methodist minister was one of two men inaugurated into the New Church priesthood when it was established.

Difficulties arose among these first members because they couldn’t quite figure out what form of church organization they wanted to have. At that time, the poet William Blake and his wife, Catherine were among those who were who interested in this new Christianity. They signed the role in 1789 at the very first General Conference of the New Church. At any rate, they had an organization and a church building, and there was a lot of enthusiasm about the New Church among a certain sort of people. Hindmarsh was interested in a hierarchical church organization, while many of the others were interested in a congregational type of church organization. Some people also felt that Hindmarsh was too authoritarian in certain ways. They thought he was not flexible in terms of how he wanted the Church to develop. This divided the fledgling Church for almost two decades.

The Church continued to grow in England, despite any coordinated effort, but it wasn’t until 1816 that the Church was actually established in the form that it currently exists today; that is, in a congregational form with a president and pastors. Pastors were initially self selected; that is, people who studied Swedenborg’s writings intensely and then offered their services to different congregations.

There was also the formation of the Swedenborg Society in 1810, a group that was (and remains) dedicated to the translation and publication of Swedenborg’s writings.

In the North of England there was John Clowes, an Anglican minister who preached to various groups, but remained affiliated with the Anglican Church. Clowes was charismatic. Hindmarsh was not. Clowes never formed a separate church organization. Hindmarsh did, and he eventually became president of the British Conference. Once formally established in1816, the organization of the General Conference has met yearly, and remains in England to this day.

Religioscope – Did the British Conference of the New Church remain a very tiny movement? What did it represent? Managing to survive for nearly two centuries is after all no small feat for a (numerically) minor religious group!

Jane Williams-Hogan – It flourished in England very much in the 19th century. It had very large churches scattered around England, concentrated particularly in the Lancashire region of England, which was also the anti-monarchical area of England. Lancashire was also the area of the industrial revolution. The New Church prospered under these modernizing forces that came together in Lancashire. So you had sixteen to twenty different churches in the Lancashire region of England. Some of these churches could seat four hundred people.

Initially they had no mechanism for formally training priests, they did not have a theological school until the 1860s, and as a result, there was not a zealous group interested in maintaining and sustaining an organization. People would come and go. Often their churches were like neighbourhood churches. They had Sunday schools and that kind of thing. At the same time you had people in France reading, translating Swedenborg, and attempting to get groups together but it was a very difficult process, whereas in England the New Church was able to establish a theological school. No theological school was established in France. In fact, theological schools for the New Church have only been established in English-speaking countries.

Religioscope – Including of course the United States…

Jane Williams-Hogan – Indeed, the books had arrived in the United States in 1784. In 1817, a year after Conference got itself established, you have the establishment of the General Convention of the Church o

f the New Jerusalem, which eventually became the Swedenborg Church of North America, as it is now known. They also established themselves in a congregational format.

Like their counterparts in England, they also prospered very much in the 19th century. In the United States, it was a century of tremendous religious experimentation and interest. Many New Church congregations were established which grew. There were a lot of intellectual readers. There were artists; for example Hiram Powers and George Inness. There were writers; for example, Ralph Waldo Emerson was a reader, as well as, Edgar Allen Poe, Walt Whitman, and Andrew Jackson Davis, to name a few. You have a lot of things going on in the 19th century, particularly in the state of Ohio.

But again there was the problem of a priesthood. They had no formal mechanism for training priests until, I believe, 1868, when you have the beginning of a theological school in Boston. So, you have people, you have these churches but you don’t have strong organizational structures. At the same time, there were people who were interested in different issues. There were discussions whether Swedenborg’s writings were inspired, or were authoritative like the Bible. There were big discussions among Swedenborgians about these sorts of things, and then there were plenty of people who would read Swedenborg’s writings and really didn’t care too much one way or the other about that type of issue, and they would take from them what they were particularly interested in and they did not concern themselves about the rest.

There was a man by the name of Henry Benade, who had a Moravian background (which has an Episcopal form of church structure) and who became interested in these teachings. He eventually established the Pennsylvania Association, which also established a school, since he felt that education was a very important tool for the dissemination of Swedenborg’s teachings. This school was founded in Philadelphia in 1876. This created tensions, because the vision of Benade was different than the vision of others in Convention. So there was a schism in 1890, which led to the founding of the General Church. It eventually became headquartered in Bryn Athyn, in Pennsylvania.

1900 was in certain ways numerically a high point for these different organizations. There were maybe six thousand members in the General Convention in the United States and about seven thousand members in the British Conference. Those numbers refer to “signed-on-the-dotted-line” people, so that you can multiply those numbers by three or four in terms of their weekly congregational size, their Sunday schools and so on, because there would be a lot of people who would attend who were not members. They might be spouses or friends. To think in terms of the whole community of Swedenborgians, one might multiply this number by three, to approximate the number of people who were organizationally connected—it comes to about forty-five thousand.

At this point, two things happened. First, you had a splinter group, i.e. this General Church that separated from Convention because of theological and organizational reasons. This became, at the moment it was founded, an international organization, which then drew people away from these two other bodies. It became a competitor in a sense, for the same market and this, I think, had an impact on the development of these churches.

Another thing that happened was that Swedenborg was read in the 19th century as a way of understanding the human mind and psychology. One of the things that happened at the dawn of the 20th century was that psychology became its own discipline. Reading the writings of Swedenborg, it is possible to bypass religion and go straight to psychology; in the 20th century, you no longer have to get psychology in a religious package, in a religious framework; it became possible to get it “straight” so to speak. And I think that development also had a negative impact on New Church growth and development. As well as the fact that both Convention and Conference never had a priesthood equal to their membership. Sociologically speaking, it is important and necessary to develop a sufficient ministry or priesthood for the kinds of congregations you have. Neither of these groups had sufficient numbers to fill this necessary leadership role.

Religioscope – What were then the developments during the 20th century?

Jane Williams-Hogan – Up until about 1970, the groups all continued doing the same thing they had always done up until about 1970. They continued in their patterns, in their ways. The General Church grew because it was starting from a very small membership of 297. It also had very wealthy members who could provide resources for the growth of this particular group, whereas because the other two groups were congregational, the money was never centralized in a way that could be helpful to their structures as a whole. So they had congregational organizations, when in many ways modern life requires bureaucratic, more centralized organizations to actually make things work.

There was also another group, The Lord’s New Church, that splintered from the General Church in 1937 as a result of, again, organizational as well as theological differences. They wanted national bishops for churches to enable these national places to be able to go their own way in terms of their theological interpretations. These people also thought that the writings of Swedenborg had an internal sense to them, and the membership of this group call his writings the Third Testament. They saw an internal sense in this “Third Testament.” This group has never grown very large, and until now has never figured out an organizational structure that would work for it. It is too early to assess these recent changes.

Around 1970, the British Conference was not growing. They had schools that got closed in England early in the 20th century, and over time they have had an increasingly aging population. In 1970, the Conference in England, the Convention in the United States and the General Church all had about 3000 “signed-on-the-dotted-line members.” Today the General Church has about 5000 “signed-on-the-dotted-line members;” British Conference has maybe a thousand signed-on-the-dotted-line members; and the General Convention has maybe 1500.

Perhaps, these groups, in a way, have decided not to grow. The Conference has, as of 2000, reorganized its structure to make it more centralized so that they can, in fact, draw on the limited resources they have to serve the people that they have and perhaps also grow. How successful this will be is problematic in my opinion. Conference must also contend with a climate in Europe, which is relatively antagonistic to organized religion although very interested in other sorts of spiritualities.

The General Convention in the United States decided to take their theological school from the east coast, because it was a losing proposition financially; and in a lot of other ways it was not really serving their purposes. Recently they have become the Swedenborg House of Studies at the Pacific School of Religion. Currently they are within an environment that is one of the most liberal theological schools in the United States. How that will go for them, in my mind, is also a little problematic but it is an interesting experiment.

The General Church is an international Church, with the broadest diversity of membership in terms of racial groups and that kind of thing. The other two groups are much more homogeneous, white upper middle class in the United States, in England it’s middle class and lower middle class, older white people. Whereas the General Church – since it is international – has people from Korea, Sri Lanka, Africa, Japan, the Philippines, and even from England, Sweden, Russia and so on. Because it is international, it has a greater capacity for variety. It has the kind of organizational structure that could work, but they are not really growing the way they think they ought to grow. Currently, they, too, are really staring themselves hard in the face to find a formula for growth. While an important question is, what is the fate of any of these groups? In particular, what is the fate of this particular group, the General Church? It, like the other New Church groups, really has to develop some kind of an approach that will draw people to it. At the current rate of membership increase, it will be hard to sustain itself, although it does grow, in absolute numbers. This is because, its rate of growth is not equal to the development in the world in terms of population increase. Thus, despite growth, its could be seen as being in decline; furthermore it does not have the human capital necessary for the things it wants to accomplish in the world. So they have developed an Office of Outreach with the idea of growing 10% a year. And it will be interesting to see the outcome, if they do.

Religioscope – Could you tell us more about what is happening in the New Church outside of the western world?

Jane Williams-Hogan – There are some very interesting developments in Africa, in Sri Lanka and in the Philippines. In Africa, over the last twenty years, there’s been relatively phenomenal growth in Ghana. You have two or three schools in Ghana. I don’t know what the membership figures are, but they have very active church groups, as there are three or four different congregations in Ghana, and at least two schools. In addition, there is a religion-friendly environment in Ghana which means that the New Church can have appeal.

Spirituality, the connectedness with the spiritual world is something that already exists in Africa and with the teaching of the New Church, this connection is now giving depth, in a sense, to very old traditions and belief systems in Africa. The writings for the New Church provide teachings that many Africans can relate to in a very unambiguous way, whereas, Westerners are always into ambiguities of every sort. Many peoples in the third world, once they find something, they assimilate it into their lives, and they begin to act and believe in this new way. So there is fairly good contact between the General Church and the Church in Ghana. There are also some very interesting efforts in Togo.

There were some people in Sri Lanka that began to read the writings; and a Ghanaian came and preached to them; on his trip, he baptized many of these interested people in Sri Lanka. That happened around 1997-99. This man traveled to Sri Lanka; they had wonderful meetings; and we now have students at Bryn Athyn College from Sri Lanka. In addition, we have students from Ghana at the college.

Religioscope – We should also not forget that there has been a longer presence in South Africa.

Jane Williams-Hogan – There has been a long presence in South Africa. I was there in 2000, and travelled around. There are two white General Church congregations. One is in Johannesburg, and the other one is in Durban. In addition, there are six or seven black Congregations. The Lord’s New Church also has severalcongregations in South Africa, and in Lesotho.

There is also an independent New Church organization in South Africa that is the result of the work of a man by the name of David Mookie. He discovered the writings in 1911 and he then founded a church based on reading one volume of True Christian Religion. He eventually got connected with the General Conference of Great Britain and that group assisted Mooki’s group for many years; but it became independent in the 1960s. When I was there, it had run into difficulties after the death of the founder’s son, Obed Mookie, who died in 1990. At that time there were some financial shenanigans by someone, causing that group to splinter. There are some fifteen thousand independent black South African members of the New Church, affiliated with the group Mooki founded. I am really interested in seeing how that group is structured and how it works because it seems to work better than some of the General Church congregations, and perhaps even the congregations of the Lord’s New Church in South Africa.

South Africa has a very high amount of New Church activity, but is still suffering from the legacy of apartheid; and whether the black an

d white groups can work together in a really productive way remains to be seen.

Religioscope – One could then say that, numerically, the largest number of New Church members are today found on the African continent?

Jane Williams-Hogan – You are right. There is also a group in Kenya. Men who studied for the ministry in South Africa have formed congregations in Kenya, and they have also started a school. There seems to be a very great deal of interest in Swedenborg’s writings in Africa, which is kind of astounding, given the fact that he was an upper-class Swedish gentleman; but that doesn’t seem to be a problem. While it is one of several problems for Western people, they have difficulty relating to that, but somehow Africans don’t seem to have a problem with it.

Religioscope – Outside the African continent, in other places, I understand one would find really tiny groups: continental Europe, Eastern Europe, Japan, Korea.

Jane Williams-Hogan – They are fairly small groups, perhaps averaging at most around thirty individuals per group. Also there are churches in Brazil that appear to be growing. At least one congregation there has a medium size group of about fifty members. The story about the Philippines is very interesting because there was somebody who was preaching New Church kinds of stuff and when the man died, his daughter took up this work. She lives both in San Diego and in the Philippines. They wanted contact with the New Church. The General Church’s former bishop Louis King got in touch with them. He went down there and found them very interested. I think there were two or three groups and this is really since 2000. Since the woman was already acting as a minister, she was ordained or recognized by the General Church as a female minister. This is very interesting because currently there are no female ministers in the General Church. How that is going to play out will be quite fascinating. I don’t know. At any rate, Bishop King flies back and forth, spends a couple of weeks in the Philippines and then comes back to the United States. So there are developments worldwide.

Religioscope – So we could say basically the New Church has been to some extent decreasing in some of its strongholds in the West, although it is developing at unexpected places – though not always in large numbers. The New Church seems to be globally more present than it has ever been in the past.

Jane Williams-Hogan – I would say that is probably true. Again, I connect that to the “charisma of the book” as the books can be sent anywhere and turn up in the most unexpected places. People find them and read them and then want to do something about it in an organized fashion.

Religioscope – A final question: the relationship of Swedenborg and the New Church to the New Age and esotericism. Quite often people tend to associate Swedenborg much less with any New Church structure than with esoteric ideas.

Jane Williams-Hogan – Yes, this is true. But that may be because someone may think that any spirituality is esoteric. Ean sotericism seems to have a concept of undivided spiritual forces. In esotericism, matter is alive; the world is alive in a spiritual way. With Swedenborg, however, the natural world is dead, but there is spirit that is alive. So there is a duality in Swedenborg, that is not present in esotericism. In Swedenborg’s writings, he describes an intimate relationship between spirit and matter; but that spirit is spirit, and matter is matter. According to Swedenborg, there is not a continuum from God to matter, so that the connection between spirit and matter is actually found within the human being, because the human is the microcosm. Every person lives in the natural world in his body, but in the spiritual world in his mind. The two worlds are connected with correspondences. Esotericism uses the concept of correspondences, but the two worldviews are really quite different. Within the Swedenborgian perspective, anything a person absorbs here in this world, like all your books, they could actually bring them with them mentally, when they go into the spiritual world after death. Any of the books you want to have you would be able to have because, in a sense, you have them in your mind.

So there is a sense that, because Swedenborg deals with the supernatural and he deals with spirituality, people think there is a more intimate relationship between Swedenborg and esotericism than there actually is. This is because it is a Christ-centred religion, while most esoteric religions are not Christian and have very little use for Christianity or Christ.

The opening up of the human ability to conceptualize spiritual reality is probably one of the greatest things Swedenborg did to allow people to have a different concept about the relationship between life and death. Death is real but the human being is eternal, because what he is, in essence, is love; and love is not material. Love is spirit. So the spirit then has a reality to it; and within that perspective it is possible that you can think positively about death. You can deal with grief in a positive way because you have a notion of a very lively, active spiritual world in which, you will be as real to yourself there, as you are to yourself here. It has a substantiality to it even though it is not fixed in the same way the natural world is fixed.

General Conference of the New Church

Swedenborgian Church of North America (formerly General Convention)

General Church of the New Jerusalem

The Lord’s New Church which is Nova Hierosolyma

The questions of Religioscope to Jane Williams-Hogan were asked by Jean-François Mayer. The tape-recorded interview was transcribed by Nancy Grivel-Burke.

Minor typographical and stylistical revisions on 19 July 2006