Religioscope – Do you think that the withdrawal from the Gaza strip will initiate in the Gush Emunim a renewal or a deep crisis, considering the contradictory signals coming from the Sharon government (withdrawal from Gaza/ promise of more settlements in the West Bank)?

Gideon Aran – let us go back to the previous withdrawal, which was Yamit in 1982. It was the withdrawal from the Eastern part of the Sinai Peninsula as a consequence of the peace accords with Egypt. No doubt, the so-called “Jewish Underground” in the territories was somehow inspired and affected by this withdrawal.

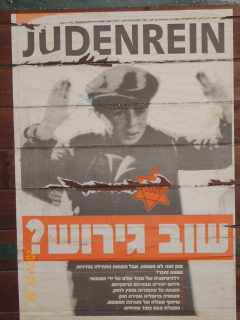

In fact, let me show you an article of mine which describes and analyses the withdrawal and starts with a poem authored by one of the hardcore settlement movement people which goes: “I have asked the pink, yellow, brown mountains of the desert in Sinai: what are you excited about?” And the answer was: “There is some intense, acute expectation in the Temple Mount”. These verses show that even on this poetic level, the true believers never overlooked the association between whatever happens in some remote areas of the Land of Israel and the centre, the very potentially exclusive centre that is the Temple Mount. In other words, political events such as the ones mentioned above have a great influence on various levels and areas of Jewish radical religiosity with political, sometimes ultra political, sometimes even violent implications. On the other hand, in the previous case – which was the withdrawal from Yamit – the impact was somehow “absorbed”. There was no real crisis. People adjusted to the new reality. We did not trace any surge in violence and there was no evidence of giving up the firm ideology or of deserting the movement. True believers neither quit, nor did they become more enthusiastic or more extreme. These are two optional reactions that betray desperation. Once again, Jewish orthodoxy proved its flexibility and ability to adjust to a new frustrating reality, to digest even “hard stuff”.

Now to be sure, no doubt, the case of the West Bank is substantially different. Here we come to a different question, which has probably been implicit in yours: “Gush Katif and the recent withdrawal is one thing, but what about the second, an eventual withdrawal from the West Bank?” This eventual withdrawal is going to be an entirely different story. In fact even the Gaza withdrawal is very different from the Yamit evacuation: people have lived there for three generations, which was not the case in 1982. At that time, the settlement was only few years old. Whereas now, it is about thirty years old. So the reality there is more solid and deeply rooted in terms of building homes, having jobs, raising families. This time – compared to the previous case – they really have much deeper vested interests. Secondly, this time, the press has intensively covered the event. Thirdly, Gush Emunim has become very rich and well established, self-confident and really sophisticated in its modes of organisation and techniques in both parliamentary and extra-parliamentary struggle. It was not the case at that time. Fourthly, from 1982 to 2005, we have witnessed several events (both regional – that is in the Middle East – and local – on the level of Israeli history) that completely modified the threshold of tolerance towards violence. Between 1982 and this withdrawal we have had two Intifadas, the assassination of the Prime Minister and so forth. That is several events in which both sides have used extreme violence including assassination, the use of firearms etc. And in this sense, you cannot compare the “naïveté” of those old times in which there was no chance of using firearms while this time everybody is armed to the teeth. Gradually, people are already accustomed to very high levels of verbal and physical aggression.

Religioscope – You said that after 1982 there was a kind of “absorption” of the Yamit withdrawal. Speaking about violence, however, there was in 1984 the plot to blow up the Temple Mount, the attempt to blow those 5 buses, and the crippling of the Arab mayors. So do you still maintain that there was a kind of “absorption”?

Gideon Aran – You should take into account a couple of things: first, the obvious identification with Gush Emunim of those inner circles – ultra-activists that employed arms and used violence – is somewhat problematic. When we speak about the settlers, about the Israeli religious hawkish right, about Gush Emunim in general, we should make a very clear distinction between the establishment and some tiny marginal clandestine groups. On the whole, I think that the main stream, the officers, the formal Gush Emunim proved to be quite restrained, abiding by the law, playing more or less – with some minor deviations – according to the democratic Israeli rules of the game. Actually the hostilities of the two Intifadas were more challenging than the recent evacuation. During the Intifada – especially during the second one – the GE settlers were exposed to all sorts of attacks and to sabotage and they suffered many casualties. Nevertheless for five years – except for some minor skirmishes, small incidents, very peripheral – there has been nothing of real magnitude, of real importance that is somehow associated with the main institutional body of the settlers. That is one point.

Now let us go back to the “Jewish Underground”, and this is my second point. The question here is: “what is more significant, more important when it comes to the “Jewish Underground”“? Is it the fact that they plotted and seriously wanted to blow up the Islamic shrine on the Temple Mount, so as to usher the erection of the building of the Third Temple or that they decided, at the last moment, to withdraw? The very intention, even the planning is one thing. Its realisation is another. Where is the centre of gravity: is it in the dream or rather in the restraint on committing the act? After all, it was not the Shin Bet, the internal security force that stopped them from doing this but their own initiative.

Religioscope – Talking about the plot to blow the Temple Mount, was there not an ideological split between Menachem Livni who wanted rabbinical approval and Yehuda Etzion who had a kind of personal philosophy?

Gideon Aran – At the end of the day – may be that there were several controversies there, may be some discussions and rivalries, may be Yehuda Etzion and Menachem Livni did not entirely agree on every point – the bottom line is that they withdrew, despite their being quite well prepared and having very specific plans, that they did not do it. Now I tend to believe that this fact is in a way more indicative, more thought provoking, more telling, than the very initiative. After all, they did not do it. As I said before, they were not stopped by any external force. It was their own decision. But now the question is: “what were the limitations imposed upon themselves and what were their inhibitions?” I tend to believe, and this is very telling, that obviously it was not just the technical obstacles but rather the need to go and ask the rabbis. I know only of one case in which a person before committing a very extreme, violent act did not go to the rabbis to ask their permission. It was Igal Amir. This is the interesting case, because a real case of zealotry is by definition one in which you bypass or ignore the rabbis. A zealot does not ask for any permission, neither for rabbinical sanction because he knows better. That is why I have always claimed – even going back to the typical cases of zealotry – that it is an act in which there are three parties involved: the aggressor, the victim and the religious authorities. By the aggression directed towards the victim, he, the zealot, settles accounts with the authorities, with the tradit

ion. Even the biblical Pinchas in the Book of Numbers (Pentateuch): it was not so much that he wanted to kill the Madianite woman and the Israelite Zimri. It was that he was not satisfied with Moses’ impotence who did not do anything, and this is the case here. So the very fact that the “Jewish Underground” asked for rabbinical sanctions says everything. It means that they were not really full-heartedly prepared to commit the act. In this case, they had some inner obstacles, some inhibitions, which I believe are very significant.

Religioscope – I come back to Yehuda Etzion. Would you consider him in the light of his personal philosophy a zealot?

Gideon Aran – Any definition of zealotry should take into account one’s ability to kill and/or be killed. It is the test of blood. When there is no blood, there is no zealotry. The usual popular meaning of zealotry is “being a fan”. In this sense Yehuda Etzion was a fan. Whereas Igal Amir was a true zealot. Nowadays whenever we analyse current issues we should take into account that we have a precedent. In 1982, there was no precedent of zealotry. This precedent applies to both religious sides: the Islamic – with the suicide bombers who are absolutely committed and have passed the test of blood – and the Jewish side with Igal Amir.

As to the recent evacuation, it was rather mild. People expected bloodshed, and brother against brother fights, which did not materialise. These acts of protest were mainly ritualistic, not real violence. This is true when it comes to the establishment. Now I do not know anything about some secret underground in which one or more than one person conspired. But such conspiracies are always marginal and not necessarily related to the established rabbis.

Religioscope – You describe Gush Emunim as an alternative to traditional Judaism, as being “a creative and potent response to the identity crisis of orthodox but modern Israelis who seek to preserve their religiosity within a Zionist framework and their Zionism within a religious framework” (1). Has the withdrawal been interpreted in Orthodox religious circles as a “victory” of the traditional Orthodox Judaism over this “new” form of Judaism? Can we observe here a renewal of Orthodoxy?

Gideon Aran – Certainly it is much too early to say. In sociology – and some historians adopted this stance as well – we use models that include lapses. For example, let us take some very extreme case like the Holocaust. Some people consider Gush Emunim or even Meir Kahane as a sort of belated response to the Holocaust. It might take five, ten or twenty years until you really digest and process and create a sort of response. Certainly it is much too early to speak about the effects of the evacuation. No doubt there is a crisis with second thoughts. Many energies and other resources are inner directed and people are asking themselves some basic questions which have not been asked so far, like questioning the very authority of the rabbis who proved to fail completely – in fact they promised something that they could not deliver – or whether they should continue waving the banner of settlement or rather direct their energies towards some alternative objectives like social problems which they have absolutely ignored so far.

The Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic movements are much more advanced in the sense that they have always known how to beautifully relate the national-religious objective with the social one providing clinics for the poor, paving roads, taking care of orphans and widows, building schools and hospitals, etc. and obviously mobilising the credits they have, the dividends towards their own. Gush Emunim is unique in this sense that it has ignored any social problems. To be sure at the very beginning there was some talk about it, but then in practice they have done nothing. Interestingly enough, now there is serious talk about such possibility, for example about resettling some areas within the limited borders of Israel. They can do a lot to develop towns where people – “ethnically inferior”, underprivileged so to speak – live or make the desert of the Negev rather than the Sinai blooming. So I assume that it is much too early to evaluate but at the same time I do see some signs, some hints, that something is “boiling” there.

And this something might come out in all sorts of manifestations on various fields.

First in religious terms. Obviously the messianic impulse of Jewish religiosity has been knocked down. Ten or fifteen years ago we could speak in terms of Israeli religious Judaism as being essentially messianic and here I relate not only to Gush Emunim but also to the Lubavitcher, the Habad movement both in New York and Israel while the Rebbe, the Messiah, Menachem Mendel Schneerson was still alive, sick but also immediately after his death. At that time messianism was at its height. Now it is undergoing a very severe crisis, obviously. After three or four decades in which Judaism has been substantially suffused with messianic fever, which is not the case anymore. So this is one possibility in the field of religiosity. Secondly in the field of politics, nothing is very clear so far. What we know is that they failed in their attempt to usurp the Likud party from within. The so-called “feiglinim” did not make it and now they are desperate. And people in despair are, on one hand, very dangerous people, and on the other hand they are really in very bad situation, which is why now it seems as if they just want to be left alone to think.

So in the next few years, I would rather expect a lot of rethinking, re-evaluating and may be new ideological or theological options will appear: either dropping messianism altogether or relating messianism to some objectives different from the territorial ones, like social problems, poverty, poor education, ethnicity, absorbing new immigrants, etc. For example Yehuda Etzion dedicated in recent years a lot of time to this campaign of salvation of Ethiopian Jews. And then I also consider the possibility of the very decline of this messianic fervour and religious Judaism, which are meant to become once again moderate, pragmatic, kept under very strong control.

People speak in terms of Jewish history as being suffused with messianism: but this has never been true, except for the Bar Kokhba revolt in the second century, the Sabbatean in the 17th century, Gush Emunim and the Lubavitcher recently. So once again, it brings us to the previous discussion: you can speak about Judaism as being really messianic, take the example of its energising three very impressive historical movements, or rather speak in terms of Jewish history in which there had been only three, four, or five messianic very short episodes. More important in terms of the emergence of these episodes is the fact that once finished, immediately all the forces were mobilised to erase them from the chronicles, and to present them as false messianism.

Religioscope – Has the recent withdrawal also triggered a crisis within the Hesder Yeshiva movement?

Gideon Aran – The Hesder Yeshiva is an integral part, a very organic component of the national religious sector. Obviously it suffered from a very hard blow, especially when it came to the very critical question: should they follow the rabbis or their military commanders? Now, no doubt, while the rabbis were stupid, and let me say it quite explicitly, stupid enough to press the question and make their students decide, 99% of those students took a very clear decision: they chose democracy, the government and their comrades which made the rabbis look like fools. It was the first time that the military/government was very decisive, clear-cut, and did not play with them. And the young soldiers preferred the state, modernity, the secular world.

Religioscope – But does this put the whole institution of Hesder Yeshiva into question?

Gideon Aran – It certainly does. Here you have three parties involved to determine the fate of the institution. One is the Rabbinate. The second is the potential audience that is the young people facing the choice to enrol or not in Hesder yeshiva. Third there is the army, which seems to be quite tough. The chief of staff threatened the closing up of several Hesder yeshivot in which the rabbis were quite frankly ordering the kids to disobey their commanders’ orders. Now as far as the young people and the rabbis are concerned, some of them, the more radical ones will certainly gravitate towards the Haredi, that is the ultra-orthodox pole, which means that they will withdraw from their Zionist commitments into the Haredi option which lives very well with the modern secular world but which is closed on itself, having nothing to do with the state. This option is also being discussed. That brings us automatically to the previous question: one of the options adopted by a certain portion of the nationalist religious sector is to gravitate towards the Haredim, that is to isolate themselves, to live on their own a semi-autonomous religious life. I would not say that they are anti-Zionist but certainly “a-Zionist” and not committed to the Israeli secular state.

From the point of view of the Haredi society, which was not Zionist in the first place, there are now impulses pushing towards joining the army. Indeed it is not so easy for the rabbis to “imprison” these young people within the boundaries of yeshiva, the Torah world: it is in a way unnatural. Especially in these days when everybody can study in a yeshiva, due to their high numbers and to the large amounts of money available there. But not everybody is qualified to do that, either intellectually or from the point of view of temperament. In history, only a minority among Jews were committed to full time Torah study. It was just an elite group, a sect of sorts. And the rest of the community was committed to a regular life: they were merchants, engineers, bankers, workers etc. Now that everybody is imprisoned within the four walls of yeshiva, which means 18 hours a day of sitting on your buttocks, studying the Talmud, there are many people who do not fit into it. These people first become a disciplinary problem, because they cannot sit there and they start drifting towards all sorts of delinquencies, unless some alternative options will be given to them to help them found or established for them to stream their excessive energies, like military service, settlement etc.

And finally one should also remember that there is another party. This party is the secular world, which after the Yom Kippour war, in the 1980s, lost a lot of its self-confidence and felt a sort of inferiority complex towards the religious world. It is not the case anymore. The secular people are becoming more confident, more secure, even politically. It is the first time that there is an explicitly secular party, Shinui which consequently puts the religious camp under fire.

Religioscope – Keeping in mind the fact that there is an opening from the Haredi world towards the army, is there a possibility that the distinction between Haredi and Gush Emunim gets blurred?

Gideon Aran – You are absolutely right. The Haredim are undergoing a process of “Israelization” and some of them are becoming sort of Zionists. It is a different version, a blend of Zionism, nevertheless. And on the Gush Emunim side, we are witnessing a process of “Haredisation” and no doubt the two have a tendency of joining in the middle. In recent years, the Haredim, though not really nationalist, state supportive and Zionist, are becoming truly the hardcore of the Israeli right wing. You should have seen the funeral of Rabbi Meir Kahane: thousands of people were present, mostly the ultra-orthodox.

They are very racist, very anti-Arab, very activist, very maximalist in terms of territory and one should take into account the fact that previously, 30 years ago, they were called “dovish” even if they were not really “dovish”, but very pragmatic, certainly not trusting military force, avoiding any active historical interference. So while Gush Emunim is undergoing change, the very same holds for the Haredi camp and one of the possible results is that some extreme sectors of both might join together. By the way, the most rapidly growing settlement in the so-called “territories” is an ultra-orthodox one, the new town of Beitar Ilit, which is “mushrooming”. The Gush Emunim and the Israeli government were clever enough to open up the territories for Haredi settlements and the Haredim being troubled by a lack of a residential infrastructure and having no money, were offered spacious apartments, relatively luxurious, very low prices which made the migration very impressive. So now you have three rather fast growing and pretty thriving Haredi urban settlements in the territories: Beitar, Immanuel, Kiriatzev. And as I said, Haredim are “trigger-happy”, they love to carry arms, they are the first to protest against Arabs, to adore Israeli military heroism while not necessarily serving in the army. So in a way they are sort of ultra-chauvinist, without being nationalistic.

Moreover most of them are not messianic except for the Lubavitcher who are anyway in deep crisis ever since their “Messiah” died. To be sure they tried hard to simply imitate or adopt the classical Christian model, that is translating the ve

ry frustrating event of the death of the “Messiah” into a jumpboard for a new emergence, actually becoming a world religion by giving it a very radical reinterpretation and talking about the “second coming”. It has not caught on so far. So actually while 10, 20 years ago we could have spoken in terms of religious Judaism being dominated by two messianic movements, the Lubavitcher and Gush Emunim, this is not the case anymore. The two most important, very resourceful, very effective, very impressive movements are in deep crisis.

Religioscope – In the weeks preceding the withdrawal from Gaza, there were discussions on Kahanist forums about the justification for an eventual suicide attack against the Temple Mount. In May, the Israeli daily newspaper Ha’aretz announced that the police had arrested members of a plot to destroy the Temple Mount and afterwards commit suicide. Do you think that there has been a shift towards suicide attacks, probably influenced by the “Palestinian suicide-bombing model”?

Gideon Aran – Not that I knew of, but religion in general and Judaism in particular has proved to be quite changeable, very adaptive and flexible but not necessarily creative. Big world religions like Islam, Christianity and Judaism are rich enough to have everything within their “arsenal”. To be sure, many elements are relegated to the margins or to the lower strata of religion. And the whole idea is to take something, which is underground or marginal and put it into the centre and invest it with some sort of activism rather than inventing something new. And I am sure that if ideas involving suicidal acts are being brought about, a way will easily be found to relate it to one of the sacred, old, archaic legacies and legitimise it, energise it simply by connecting it or relating it with some sort of sanctioned idea. You know in Judaism, or in Islam, you can find everything: a point of view and its opposite, all sorts of variations and each could be easily backed up by particular citations. This also applies to suicide. And actually Islam gave us a very persuasive example: on the one hand you find all those Islamic “experts” who quote and re-quote that Islam is very much against suicide, not to speak of the apologetics of Islam, all those professors in the West who try so hard to present it in a nice way. You can very easily pile up hundreds of citations that clearly show that Islam is very much against suicide. On the other hand, history shows very clearly that if you need it or have some sort of motivation, or good reasons to employ suicide, you use it and yet at the very same time you present yourself as the champion of Islam, like Bin Laden. I tend to believe that Bin Laden is quite genuine about it, he is not cynical, he is not a charlatan. So this is Islam: Islam is not just some old text, the Coran, Islam is the religion, which is currently practised by the Muslims.

In this sense in 1666, for two years, Judaism was Sabbatean and messianic despite the fact that immediately after the episode of Shabbatai Zvi was declared a deviation from Judaism.

And in this sense, Timothy McVeigh is not less Protestant than one minister in Washington who is very much against him. So I do not know what authority can define the limits of religiosity. The very test of rich, great world tradition is its heterogeneity, its variance, its flexibility. Otherwise it would not survive. What has made it survive during hundreds of years is its ability to contain so many contradictions.

So the same holds for your question about Judaism: you hear all the rabbis – just as the Islamic clerics – preaching against suicide and at the very same time you see what seems to me “good” Jews or Moslems commit suicide and really believe that they are following the path of the prophets. In recent years, we have learned that world religions – Christianity, Islam, Judaism – are not limited to the sacred old texts. There are so many additional layers, strata of interpretation, of learning, of preaching, of evangelising. So who is more important: is it the prophet Moses or Christ or the middle-aged – not necessarily very intelligent – priest in some remote village in Sudan, or Palestine or some neighbourhood in Jerusalem who teaches on the Sabbath his community about the duties of religion?

Religioscope – So you do not exclude the fact that one day we might have Jewish suicide bombers?

Gideon Aran – Certainly I would not exclude such a possibility, which does not mean that I can see such one now. Not at all. But this is certainly a possibility and there are some chapters in Jewish history in which people in fact did commit suicidal acts and they were regarded as saints, sanctifying the name of the Lord. In the Middle Ages, during the first Crusade in 1096 in Central Europe, in Germany and France, in the Rhine valley, in Mainz, in Treves people committed suicide for religious reasons, killing their kids, their spouses and themselves ostensibly Kiddush Hashem, meaning “sanctifying the Name of the Lord” and ever since being considered by the religious establishment as saints. Just like the martyrs in the early history of the Christian church and just like the Shahada in Islam.

Religioscope – Has there been debates similar to those preceding Yitzak Rabin’s assassination to declare Ariel Sharon “Din Moser” [traitor to the Jewish people, giving information or territories to the Gentiles] in the months preceding the withdrawal ?

Gideon Aran – No, as far as I know, even if I admit that I know very little about the issue in terms of real occurrence in the field. But generally speaking, I rather suspect that in the post era of the assassination of the Prime Minister, people are probably much more careful about playing freely with such ideas like the “Moser”. Now they are aware of something that they were not much aware of before: their own power. These people who are very effective educators did not take themselves seriously enough, to realise that as they speak and teach about certain things, their students will take them literally. And in fact, I would say, this is rather the “art” of being a rabbi or a religious educator: it is a very tricky, nuanced job.

How can one speak about ideas in general so as to convey their value, their norms to inspire people and then not really translate it into real action? After all, zealotry in Jewish sources is actually a positive value. One should be a zealot. That is to stick to the Torah command, adhere to the divine word, take it very seriously but yet not go – in a very consistent way – to the outmost conclusion. How can you convey the idea of zealotry without making people take their knives and kill other people without trial? It is a very tricky job and this subtlety is now much more acutely realised by the rabbis than before, because now they are aware of the possible results: one of their students could take it seriously. You can easily speak about the idea of “Moser” if you know a priori that nobody will take you too seriously so that you can convey the general idea and that is it. I think that the whole process of civilisation is to play this very delicate, nuanced game between ideas and their actualisation. It is a very finely shaded “game” and you might miss it. Now it is much harder to miss that than before because we have already experienced a failure. It was essentially the failure of the rabbis, the religious educators who were not fully aware of their own potential, of how effective they could be. Their impact is very strong. Every religious educator wants his public to be somewhat zealous, to be a hardened believer, and once the public follows the commands literally, with no sense of humour, no irony, seriously, this can be hell. Obviously the first victim will be the “church” itself. The

example of the Christian Reformation is a great one: Martin Luther, after all, is seen – as far as the Church is concerned – as simply taking Christianity too seriously and obviously he killed the Church. And the Church was the first to lose by having one of its “officiants” who took the message too seriously.

Think of Igal Amir. Actually by doing what he did, he, at the same time, took his rabbis very seriously – as opposed to all his friends who went with the rabbis up to a point and not one millimetre beyond – but he also completely ignored them. He knew better, he had a direct contact with God. He did not need anymore the rabbis, he knew the word so he could bypass this mediation of the “Church”, the rabbis, the sacred text and he killed.

Notes

1) Gideon Aran, “Jewish Zionist Fundamentalism: The Bloc of the Faithful in Israel (Gush Emunim)” in Martin E.Marty and R. Scott Appleby, Fundamentalisms Observed, Chicago University Press, Chicago and London, 1991, p.297).

Jean-Marc Flükiger, contributing editor to the French speaking website Terrorisme.net, talked with Dr. Aran. Religioscope would like to thank Mrs. Margareta Flükiger for her improvements and copy-editing of the English version of the text. For a French translation of the interview, see www.terrorisme.net.