Hear “liberation theology,” and you might think of the revolutionary, and reactionary, fervor that rocked Central America in the 70s and 80s. Liberation theology evokes precisely that mix of romance and tragedy that is so Latin American — passionate priests and oppressed peasants dreaming of, and working for, better social conditions only to die at the hands of right-wing death squads.

By murdering such luminaries as El Salvador’s Monsignor Oscar Romero and Ignacio Ellacuria, the groups behind the killings hoped to kill liberation theology itself. But as Central American wars fell off the radar, so did the theology of the poor.

Relative economic and political stability kept guerillas and liberation theology down in Venezuela. Yet the latter managed to find a foothold here as it did around the region.

Liberation theology attracted many of Latin America’s poor by combining spiritual and social concerns. The guerilla movements and the repression that surrounded its birth blessed and cursed the movement. After growing up fast, liberation theology settled down to figure out its future.

Although the Roman Catholic Church has plenty theologies, liberation theology has become almost synonymous with “Latin American theology,” so closely do people identify the region with this spiritual leftism.

Like any set of ideas, liberation theology has had its ups and downs. But as liberation theologians like to put it, so as long as social misery exists, there will be a need for a theology that opts for the poor.

Liberation theology 101

Despite its heavily European slant, the Second Vatican Council, which ended in 1965, gave Latin American theologians encouragement. Applying the Council’s ideas to the Latin American context was left for them to undertake.

Liberation theology “develops as the Latin American response to [the Council],” said Father Pedro Trigo, Venezuela’s most important liberation theologian. “Those of us who read the Council wanted to [adopt it].”

That led to 1968’s Latin American church council in Medellin where the hierarchy came out in unanimous support of the poor. Although “liberation theology” grew out of Medellin, it only became known as such when Latin American theologians started building on the conference’s results.

Many consider Medellin not only the birth of liberation theology, but of the Latin American Church. “Medellin had great importance in the universal church.,” said Father Trigo. “It was the birth of the Latin American church. Other churches were very surprised by [our] strength.”

According to Trigo, Medellin gave Latin American clergy a “citizenship charter.” Priests knew that their work enjoyed the the support of the Latin American Church’s hierarchy.

“If the highest authority of the Catholic Church in Latin America meets and concludes that,” explained Trigo, “then I’m not off base. I’m not going astray from Christianity by doing this. On the contrary, I’m realizing Christianity. If you’re holed up in the church, it’s you that isn’t fulfilling Christianity.”

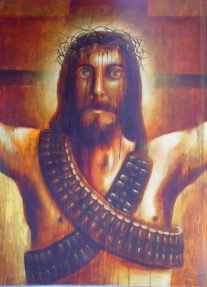

Rather than ignore earthly misery, liberation theology seeks social as much as spiritual well-being. Basing itself solidly on the Bible, liberation theology endorses the “preferential option for the poor.” It’s not that Jesus Christ doesn’t care for the rich, but he has his priorities.

Asked about Christianity’s purportedly socialist elements, Father Carlos Bazarra, the author of What is Liberation Theology?, claims that “the Bible has a very strong socialist dimension.” Besides being charitable, Jesus cut a subversive figure, inspiring many a socialist through the years. However you slice it, poor people just seem to need religion more. Liberation theology, then, met a need among the region’s poor.

“It awoke in Latin America and Venezuela a tremendous joy and enthusiasm,” said Father Trigo. “People were very happy seeing priests coming to their level, having a voice in their church, organizing themselves-that was a wonderful thing for them that gave them great hope.”

The Council’s great contribution was to declare Christianity a historical religion, according to Trigo. By doing so, Christianity’s goal of creating brotherhood on earth took precedence.

“We have to fulfill Christianity in history,” said Trigo. “We have to make real the fraternity of God’s children.”

Liberation theologians gave fraternity a socio-political meaning by applying the Bible to social reality.

The liberation theology method comes down to “see, judge, act.” Liberation theologians “see” the social misery around them, “judge” it according to the Bible, then go out into the world to “act” according to a theology that promotes the self-realization of the poor.

“We emphasize the subject today,” according to Father Trigo. “What God most wants is to strengthen the subject.”

Liberation theology’s concern for the subject comes down to the individual’s dignity and worth. That implies intensive pastoral work of the kind few communities enjoy, partly because of the sheer lack of priests. Within these congregations, respect for the subject means participation.

“The church can’t be a church of masses and leaders, but an organic church where everyone gives and receives,” said Father Trigo. “So where is that supposed to start? Well, with those privileged by Jesus, who are the poor. Those are the base communities. The Church starts to articulate itself from the base, and that’s why I [say] that the communities come first.”

Growing up fast

After the excitement of Medellin in 1968, and the development of liberation theology’s theory and practice, came the Puebla conference in 1979.

While liberation theology gained strength and followers, resistance to it within the Church also increased. At Puebla, a powerful wave of Latin American bishops came down hard against the burgeoning movement.

“Bishops saw it as aggressive,” according to Father Bazarra. “Liberation theologians weren’t allowed in the Assembly, so they had to talk to the bishops in the hallways to try to influence them a bit.”

According to Trigo and Bazarra, Puebla officially ignored liberation theology. It received no specific mention anywhere in the conference documents. Although liberation theology lost some institutional ground, Puebla still fundamentally followed the Medellin line.

Trigo indicates that “Puebla repeated many of the declarations from Medellin.” But where Medellin made the poor “central,” Puebla gave them “preferential” status, showing the subtle shift. Still, the years since Medellin had strengthened the movement in experience and maturity.

“By this time, there had been a lot of martyrs,” said Trigo. “So they said, ‘Oh, that’s a sign that it’s good. The fact that a lot of powerful people have withdrawn their support we take as a sign of faithfulness to Jesus Christ.’ That was Puebla.”

Although the Vatican often keeps its distance from these issues, it occasionally expresses its concerns. The then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, today’s Pope Benedict XVI, wrote a paper on liberation theology where he expressed concern that Marxist elements were getting mixed up with theology.

Father Bazarra, who acknowledges the influence of Karl Marx’s thought on liberation theology, considers it a simple misunderstanding.

“Theologians openly used Marxist methods,” explains Bazarra. “But [some people] didn’t know how to distinguish between Marxist methods and Marxist doctrine.” One thing was to use a Marxist analysis, but another was to promote violent revolution, added Bazarra.

Bazarra cites Matthew, chapter 5: “Well traveled are the poor because the kingdom is theirs.” For Bazarra, “opting for the poor comes with solid backing. It’s a gospel truth.”

Many have speculated about liberation theology’s demise, but the movement seems to be doing fine. Its significant contributions to Latin American theology as a whole have been fully incorporated, according to Trigo.

Archbishop of Merida and President of the Venezuelan Episcopal Conference (CEV) Baltasar Porras supports these claims.

Liberation theology “vindicates the people’s fundamental values,” he said in a phone interview. “It continues to be relevant. Being based on Latin America’s reality, it gives the region’s people a sense of identty.”

If the Vatican had a problem with it, “it would have been expressed,” adds Porras.

Still, liberation theology is at a crossroads. According to Bazarra, some consider the movement’s mistakes significant enough to do away with it altogether. Others want to push ahead with liberation theology as it stands today. Bazarra himself takes the middle ground, which advocates fine-tuning the theology.

“Talk of class struggle doesn’t seem based on the gospel,” admitted Bazarra. Along with the liberation theologians that call themselves Marxists, the vast majority sound like socialists, although it’s the extremists that talk of class struggle.

Besides rejecting neoliberalism, liberation theologians promote such radical changes as full employment and vast social programs. To Americans, that might sound like bolshevism, but to Europeans and Latin Americans, liberation theology just sounds like another part of a long tradition of social justice activism, but with a religious twist.

The people come first and last

Liberation theology’s message of God’s love for the poor has found a warm reception around the region, including Venezuela.

Berta Perez, who works in day care, lives in Barrio Bolivar in the vast Petare slum. Every two weeks, Father Trigo visits the Group of Hope, where Perez is a member, to read and discuss the Bible.

In our phone interview, Perez sounded as happy and peaceful as if she were already living in that socialist Kingdom of God.

“I’ve learned to trust in the other, to believe in my neighbor,” said Perez. “I used to discriminate against people, but now I see that their behavior owes to their upbringing,” she said, expressing the kind of Christian compassion and solidarity of which liberation theology is so fond.

“You have to see your neighbor through charitable eyes,” continued Perez. “He needs more than we do,” she says, referring to her Petare neighbors who struggle with desperate poverty and related social ills.

Consuelo Chima left her native Colombia 30 years ago only to end up living in a Caracas slum. She used to walk in her barrio, wondering what she was doing there.

“I would ask myself, ‘When will this torture end?'” she explained. “Then I realized that I was part of it.”

Liberation theology’s emphasis on solidarity and putting oneself in the other’s shoes has touched Chima deeply. “We spend our time walking all over our brothers when we must see God’s face in theirs,” she said.

With so much worldly misery, liberation theology yearns for a world of brotherhood and sisterhood. It comes down to teaching people to think collectively, not individually.

You might also think of the liberation theology project of creating the Kingdom of God on earth as just an effective way to save souls on a larger scale, and preparation for the heavenly kingdom itself. It all comes down to seeing God in each other and acting accordingly.

As Bazarra puts it, “Jesus insists that we’re all brothers. No one saves themselves alone, but we save each other together.”

Or as Perez puts it, “To feel like a son [of God], you must be a brother.”

José Orozco

Born and raised in Chicago, José Orozco works as a freelance reporter in Caracas, Venezuela where he covers social issues.

© 2005 José Orozco. All rights reserved.