The Orthodox Church in China was given a status of autonomy by the Moscow Patriarchate in 1956 and had two Chinese bishops, several priests and possibly up to 20,000 faithful in the early 1960s.

But it has never fully recovered from the turmoils of the “cultural revolution” of the 1960s and its antireligious policies. In December 2004, the last Chinese Orthodox priest living in China, Father Alexander Du Lifu, passed away in Beijing at the age of 80. He did never manage to get permission from the government to open a church in Beijing: the authorities argued that the community (about 300 faithful) was too tiny.

However, there are efforts from several sides to revive Orthodox life in China, and a few Chinese students are reported to be currently training in Russian theological schools. According to estimates by Father Dionisy Pozdnyaev, who is in charge of Chinese affairs at the Department of External Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate, there are some 13,000 Orthodox faithful living in China. There are parishes – without clergy – in Xinjiang, in Inner Mongolia and in Harbin, where the Russian church building is a local landmark. The Moscow Patriarchate would like to see the Orthodox Church recognized officially, but its small size seems to present an obstacle.

Attempts to revive Orthodoxy in China also take place in virtual space. An Orthodox believer of Chinese background living in the United States, Mitrophan Chin, is the webmaster of the website Orthodoxy in China (http://orthodox.cn), which was launched in Spring 2004. In this interview, he tells us more about the history, current situation and prospects for the Orthodox Church in China.

Religioscope – How did Orthodoxy reach China first, more than 300 years ago?

Mitrophan Chin – Orthodoxy reached China with the eastern expansion of the Russian empire across the Siberian Far East in 1651. At around the same time in 1644, the Ming dynasty was overthrown in China by the Manchurians who introduced the Qing dynasty which lasted until the Nationalist revolt of 1911. The Russian Cossack settlements along the Amur River at Albazin eventually was met by fierce attacks by the Chinese army in 1685 which led to the downfall of Albazin, and the captives were taken to the capital city of Beijing.

Religioscope – The first Orthodox in China could thus be described as “immigrants”. When did missionary activities directed toward Chinese begin, and how successful were they?

Mitrophan Chin – Missionary activities started when a number of the original captives of the Albazinians were given the honor to serve the Chinese Emperor Kangxi in the Imperial capital of Beijing in one of the most prestigious banners of the honor guards. The first Orthodox priest, Fr Maxim Leontiev, was sent unwillingly to provide spiritual guidance to these new Albazinian immigrants. An old Buddhist temple was provided at the northeastern corner of the capital, and it was converted to an Orthodox chapel bearing the name of St Nicholas the Wonderworker in honor of the miracle-working icon that Fr Maxim brought along with him.

Thus the seed of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission has been planted on Chinese soil. In the 200 years leading up to the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, the Mission took in only a small number of indigenous Chinese converts, mostly through inter-marriage with the Albazinians. This stood in stark contrast with active missionary efforts by rival Catholic and Protestant missionaries.

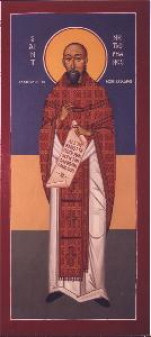

Religioscope – Orthodoxy in China had its first martyrs at the time of the uprising of the Boxers, which not only targeted Catholics and Protestants, but Orthodox as well. Your Christian name, Mitrophan, is the name of a martyred Chinese priest, isn’t it?

Mitrophan Chin – St Mitrophan, along with over 200 other Chinese and Albazinians in Beijing gave their lives up for the Christian faith during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, or the Yihetuan Movement as the Chinese called the uprising. Albazinians at this time have pretty much assimulated with the local population after two centuries of cohabitation. Their outward appearance is not much different from the majority Han Chinese population even though ethnically they consider themselves of Russian descent.

Religioscope – After the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, many Russians fled East and settled in China, where there was during a few decades a very active church life. When did those Russian emigrants then leave China? Are there still some of them left?

Mitrophan Chin – The Orthodox population swelled in the 20th century in China, mostly due to the influx of white Russians. At the same time, the Boxer uprising had not stopped the blood of the Martyrs from bringing forth a new generation of Chinese believers. Archimandrite Innokenti Figurovsky, who in 1902 became the first Bishop of Beijing, initiated translations of liturgical and catechetical Orthodox material for the first time into spoken Chinese called guanhua.

This was considered the golden era of Orthodoxy in China, with many churches being built. Unfortunately, most of the Russians fled China when the Communists took over in 1949. Some returned back to Russia but many others immigrated to Australia or America.

The famous St John, who was Archbishop of Shanghai, was one of the last to leave when the Communists took over and eventually settled in California. Also, Fr Elias Wen, who was the rector of the Church dedicated to the Surety of Sinners Icon of the Theotokos in Shanghai fled to Hong Kong and eventually immigrated to San Francisco. Fr Elias is the oldest Orthodox priest still alive and will be approaching 108 years of age this November. May God grant him many years!

Also, the priest Michael Wang, and protodeacon Evangelos Lu stayed behind in Shanghai and suffered much through the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). They have likewise reached an old age and have withdrawn from active clerical involvement as there are no functional Orthodox Churches in Shanghai. Another protopriest Michael Li, also originally of Shanghai, immigrated to Australia and serves as the spiritual father of Russian-Chinese Orthodox Missionary Society of Sydney.

Today, there are a few hundreds of Albazinian or Russian descent who consider themselves Orthodox that reside in each of the major cities of China, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Harbin. Many more are scattered in the western and northern autonomous regions of Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. In all, the most recent Chinese census have recorded around 13,000 Chinese citizens of Russian descent.

Religioscope – How did the Church first manage to continue its activities under the Communist government? What happened then to Chinese Orthodox at the time of the “cultural revolution”? Did some type of underground church life continue, insofar we know it?

Mitrophan Chin – The Church was required to be independent by Chinese government. Therefore the archbishop Victor consecrated archimandrite Vasily to be the first Chinese bishop of Beijing in preparation to lead the Church to autonomy which was eventually granted in 1957. The Cultural Revolution destroyed most of the Church buildings and many believers were persecuted. Church life was practically eliminated and the believers have to resort to reader services in private homes to continue living their faith.

Religioscope – In recent years, there have been attempts by several Orthodox Churches to help Chinese believers. The Moscow Patriarchate has been quite active, including attempts to convince the Chinese government to register the Church. The Ecumenical Patriarchate (Constantinople) has established a diocese in Hong Kong – which is now part of Chinese territory – in 1996, serving South Asia and the Far East. Moreover, priests of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia have also been regular visitors to the Chinese mainland. Those visiting priests have performed baptisms and celebrated liturgies for scattered communities of believers. Would you please summarize those efforts?

Mitrophan Chin – Efforts by non-indigenous priests have been hampered, including the recent deportation of an Orthodox priest who was secretly crossing the border between serving the spiritual needs of the Orthodox Faithful in Xinjiang in the western frontiers of China in December 2003.

The Chinese government is usually flexible with small group prayers in private homes, but they will start noticing if there are more than a handful gathering together. Visiting priests usually have to work within the supervision of the State Administration of Religious Affairs if they do not wish to encounter any obstacles, and for the most are only allowed to hold services for foreign compatriots working or residing in China. Such services are normally held in an embassy and are off limit to Chinese believers.

Religioscope – The major step to be taken seems to be the registration of the Church. Are there indications that this might take place in a foreseeable future? And what about those Chinese priests now in training in Russian seminaries?

Mitrophan Chin – The Chinese seminarians in the Russian seminaries do hope to return back to China to serve the Orthodox faithful there. This is a sensitive issue and requires the blessing of the Chinese goverment and their future is uncertain.

Russian President Putin has visited China, and has promised the Bishops Council of the Moscow Patriarchate that he will bring up with the Chinese authorities during his visit to allow an iconostasis which has been held up in customs for four years, to finally enter China to be installed in a church temple built by the Chinese goverment in 1999 in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

The Chinese government has been seen as more accomodating in recent years including allowing a hieromonk from Russia to visit the Pokrov Church in Harbin to hear confessions in both Russian and Chinese in July 2004, and also the August 2004 visit by Russian Bishop Mark to Beijing at the official invitation of local religious leaders and the State Administration of Religious Affairs.

Religioscope – I understand that there are also efforts for reaching diaspora Chinese. For instance, a few months ago, the Russian Orthodox Church has decided to celebrate liturgies in Chinese in Vladivostok and other places of the Russian Far East. Are there already small groups of Chinese-speaking Orthodox outside of mainland China?

Mitrophan Chin – Vladivostok Diocese has a creative missionary endeavor by actually allowing its church to serve as a one of the tourist sites for Chinese tourists visiting the city. The church has prepared an explanation of the Orthodox Church and its divine services in Chinese which is given to the tour guides to explain to the visitors, and at the end of the tour, the tourists actually get to light a candle in front of an icon of the Chinese Martyrs.

Not only tourism but Chinese immigrants outside the Chinese border in Russia have swelled tremendously. They have been seen as a rival economic force in Russia, as evident when the recent Bishop Council of the Russian Orthodox Church brought up this demographic issue with President Vladimir Putin. Putin turned the table around and asked the bishops about the conversion of the Chinese to Orthodoxy, since Orthodoxy has always been universal or catholic, and, furthermore, Putin emphasized that each person’s spiritual state is important.

Religioscope – Let’s now come to your website. Orthodoxy in China – http://orthodox.cn – seems to be on its way to become a major ressource for Orthodox material in Chinese as well as for information on Orthodoxy in China. Could you tell us more about the content and purpose of this website?

Mitrophan Chin – Orthodox.cn is created to be the portal of everything you will ever want to know concerning Orthodoxy as it developed in China and its environs, and especially where it is today and where it will be tomorrow. Catechetical literature and liturgical texts in classical and modern Chinese are gathered here for easy access for anyone interested in learning more of what Orthodoxy have to offer.

Links to various Internet resources and Chinese Orthodox discussion boards are also provided to take advantage of the strength of the Internet in providing a wealth of information and exchange of ideas which no one site can provide.

News articles related to Chinese Orthodoxy from Russian language media are translated into English and disseminated to keep the international English-speaking community in the loop concerning missionary activity made from the Russian Orthodox part of the world.

Religioscope – You intend also to make liturgical and devotional material available in Chinese. Are most Orthodox liturgical texts already available in Chinese? Are they being reprinted, or is the Web currently the best solution to make them available again?

Mitrophan Chin – Currently, an online library of most of the extant classical Chinese Orthodox text that were produced in the 19th and early 20th century Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in China have been scanned in and being made available for free distribution via the web, which is the most economical and quickest way for those in China to get a personal copy of these rare historical texts. More recent Chinese translations suitable for the younger Chinese generation have also been made available online for the daily prayers with various canons and akathist plus the divine liturgy of St John Chrysostom. Most of this freely distributable material can be burned onto CD upon request for those in China without convenient Internet access, and they are encouraged to copy and share with family and friends.

Religioscope – An ambitious project which you have is the Chinese translation of the Prologue of Ohrid, a collection of lives of the saints for every day of the year…

Mitrophan Chin – This project has been spurred by a Hong Kong Protestant who did preliminary translation of half a year’s readings of the the lives of saints section of the Prologue of Ohrid. He has passed the torch to a Chinese Orthodox convert currently living in Romania to revise and complete translating the rest of the readings including hymns, contemplation, reflections and homilies. The fruits of this project will greatly enrich the daily devotional life of the Orthodox faithful in China and also to introduce the riches of Eastern Orthodoxy to our non-Orthodox readers.

Religioscope – While your website is a useful resource for people who would like to know more about Orthodoxy in China, it is also meant as a service to Orthodox faithful living in mainland China, a country where there are already several dozens of millions people online. Do Orthodox believers in China use the Web and write to you for material?

Mitrophan Chin – Most Orthodox believers that are online are mostly converts and are usually self-motivated in seeking out the truth. They usually post anonymously to various online religous message boards to ask questions about the Orthodox faith. In the physical world, m

any times they would be drawn by the beauty of some of the restored Orthodox churches in China and would travel to visit such former churches like the St Sophia in Harbin or they may be curious and go seek out the existence of any former Orthodox church buildings that may have survived the destruction caused by the Cultural Revolution and ask around if there are any cradle Orthodox believers in the vicinity. Since mainstream Chinese media lacks coverage of Orthodox concerns, the web site also provides a much needed international and domestic Orthodox newsfeed in Chinese.

Religioscope – Are there also other Orthodox websites in Chinese?

Mitrophan Chin – The parish website of Holy Trinity Orthodox Church in Taiwan is also in Chinese, but uses traditional Chinese characters which are different from what is taught in mainland China which uses simplified characters, introduced by the Communist government to combat illiteracy among the vast Chinese population. The Holy Trinity parish is under the pastoral care of the Metropolitanate of Hong Kong and South East Asia, and His Eminence Metropolitan Nikitas has given his blessing to allow the use of their Chinese Orthodox material from their site to be hosted on Orthodox.cn in Simplified Chinese catered to the mainland Chinese audience.

Religioscope – And what are your next projects for the development of the website?

Mitrophan Chin – One of the next projects includes the Chinese translation from the original Russian accounts of the 222 confessors and martyrs of the Chinese Orthodox Church who fell victim in Beijing in 1900, drawn from the archives and first published in the January 2000 issue of Chinese Messenger (Kitajskij Blagovestnik) (http://www.chinese.orthodoxy.ru/russian/kb3/Martyrs1.htm), the official Russian language magazine of the Study Group on Orthodox Affairs in China organized by Department for external church relations of Moscow Patriarchate. The Chinese translation of the accounts can be sponsored with a dedication to the health or in memory of loved ones noted on the bottom of each sponsored page, as a means to compensate our translators. These accounts have been recently translated for the first time into English and can be read at http://www.orthodox.cn/history/martyrs/.

The interview was conducted online in October 2004. Mitrophan Chin was interviewed by Jean-François Mayer.