This movement is one of the eight major groups derived from the work of the reformer Said Nursi (1873–1960), author of several volumes of Qur’anic exegesis known as Risale-I Nur. Nursi made an attempt to respond to the debates of his time (emergence of the new republic and Kemalist secularization efforts): he became the source of a powerful movement active in Turkey. Hakan Yasvuz explains:

“The Nur movement (also known as Nurculuk) differs from other Islamic movements in terms of its understanding of Islam and is strategy of transforming society by raising individual consciousness. As a resistance movement to the the ongoing statist modernization process in Turkey, it is forward looking and proactive.”

Regarding the Gülen community, its impact is not limited to Turkey: putting into practice Nursi’s educational ideals, the community has created more than 300 modern, high-quality schools (including high schools), not only in Turkey, but also in several other parts of the world (primarily in Central Asia and the Balkans, but also in more exotic places, such as Mongolia or Bangladesh as well as in some Western cities). The curriculums of these schools do not have any explicitly Islamic content. Gülen aspires to create an educated elite and does not see any conflict between reason and revelation. His schools also contribute to the development of Turkish influence abroad.

At the end of two introductory chapters, which put the movement into context, co-editor Hakan Yavuz (associate professor in political science at the University of Utah) claims that “this movement opens new venues for the radical reimagination of tradition”. Gülen’s community combines Islam and Turkish nationalism. Moreover, it is “secularization-friendly” – and also American-friendly, which is not very common today in the Muslim world, but apparently derives from an assessment of what is best for Turkish interests.

In order to find out more about the Gülen movement, Religioscope put several questions on the subject to Hakan Yavuz, considered to be one of the best academic experts on the movement. He agreed to share his insights with us.

Religioscope – Fetullah Gülen has emerged as one of the manifestations of Said Nursi’s legacy in Turkey. Could you please first summarize some of the key features of Said Nursi’s teachings?

Hakan Yavuz – As far I know, Said Nursi attempted to empower Turkey’s Muslims by updating Islamic terminology and language. He tried to provide them with a new vocabulary in order to allow them to participate in modern discussions and debates on issues like constitutionalism, science, freedom and democracy. So one of his primary goals was to empower Muslims with a new cognitive map.

Secondly, he tried to provide a new, flexible Muslim identity.

Thirdly, he stressed the idea that religion and science are not in tension: they are not mutually exclusive, but can work together. In a way, he tried to vernacularize science and modern discourses in an Islamic idiom, to facilitate the dissemination of scientific knowledge in Muslim countries.

These, essentially, were the three goals of the writings of Said Nursi.

Religioscope – Fetullah Gülen never met Said Nursi personally. How does his own teaching fit into Said Nursi’s legacy? And what are the relations between the group around Fetullah Gülen and the other parts of the Nur movement?

Hakan Yavuz – The Nur movement went through a number of processes of fragmentation or pluralization: firstly, as a result of political debates; secondly, as a result of class distinctions; thirdly, as a result of ethnic divisions between Kurds and Turkish Nurcus; and fourthly, in terms of the differences between highly-educated and less-educated Turks. This has led to different understandings and different groupings within the Nur movement.

The Gülen movement emerged very much out of the Nur movement. Yet there are certain characteristics that Gülen brought to it. This is why I call it a neo-Nur movement. In terms of nationalism, Gülen is more Turkish nationalist in his thinking. Also, he is somewhat more state-oriented, and is more concerned with market economics and neo-liberal economic policies. These, in my opinion, are the three major characteristics of the neo-Nur movement.

The Gülen movement tries to move from practice to ideas. Practice is important: action is very significant. In its view, Islam is not only about praying five times a day and reading the books of Said Nursi, but acting, doing and creating institutions. In that sense, the Gülen movement is more worldly: it wants to create heaven in this world – education system, hospitals, institutions, and so forth. So whereas Said Nursi stressed cognitive understanding, Gülen is more action-oriented.

Religioscope – If we consider the context of contemporary Turkey, there is one key element: the harsh forms of secularism that Kemalist Turkey developed. This kind of secularism came to be a kind of state ideology. How do the Nur movement in general and Gülen specifically deal with this reality of secular Turkey?

Hakan Yavuz – In Turkey, there are two competing conceptions of modernity. One is top-down modernity, also known as Kemalism, the ideology of Mustafa Kemal, the founder of the Turkish Republic. This ideology has two pillars: nationalism and secularism. Secularism is very much equated with modernization and Westernization in Turkey. It eventually became the legitimizing ideology of the governing elite. Secularism does not necessarily mean separation of religion and politics. But as it increasingly came to define the identity of the ruling elite, it generated a major reaction from the Anatolian masses and the periphery. This reaction articulated itself against secularism.

The second conception of modernity in Turkey is a bottom-up modernity: here modernity is not an alien and negative thing. The Turks should enjoy it, but it should be negotiated and redefined. It should also be internalized by the masses rather than imposed by the state.

With those two different conceptions of modernity, you have also two different conceptions of secularism in Turkey. One is the top-down modernization-project conception of secularism: it is very much a laïcisme in the French sense. This approach means that there is no room at all for religion in the public sphere, resulting in the cleansing of religion from the public domain. Science becomes the guide, while religion is something negative: something to get rid of.

The second form of modernity – i.e. bottom-up modernity – allows room for religion in the public sphere. Its conception of secularism is in line with the Anglo-Saxon notion of this concept. Religion is seen as a source of morality and ethics. It also does not see religion and politics as being necessarily in conflict. However, it does not want religion to become a tool of politics, because if something then goes wrong in politics, people will blame religion.

The Nur movement always wanted religion to remain above politics, because it was concerned that politics would corrupt religion.

Today, in Turkey, the balance of power is shifting toward a bottom-up conception of modernity and a new vision of secularism. Gülen very much represents this approach, and he is an agent of this transformation. He has played a key role in transforming people’s minds and has led them to a new understanding of a bottom-up modernity.

Religioscope – You have described the Nur movement as a movement to cultivate faith without entering into a confrontation with modernity. What are its methods for achieving this in contemporary Turkey?

Hakan Yavuz – I understand modernity in terms of a market economy, human rights and creating new spaces for individual differences. The Nur movement is a modernizing system of faith and a modernizing activism generated and supported by Islam. Islam and modernity are not necessarily in conflict: they can work together.

In order to preserve their uniqueness and respect the uniqueness of others as well, Muslims need to share a new legal code, and to have a free-market economy, private education and free thinking. All these aspects of modernity have been internalized, but also disseminated and legitimized, by the Nur movement, which has stressed the idea of becoming and being a Muslim in the modern world by supporting and consolidating modern institutions of democracy, the rule of law, a free-market economy, and so forth.

Religioscope – From an organizational viewpoint, how does the Gülen movement express itself? As one speaks with followers of Fetullah Gülen, there is an obvious reluctance to acknowledge the group as an organization. Since the title of your book mentions the Gülen movement, do you consider this word as the most appropriate description? Or would you rather speak about a network? Sometimes, followers describe themselves as a cemaat (community).

Hakan Yavuz – This is an excellent question. Is this a movement, a community or a network? How should it be seen?

I use the term movement, because a movement has a collective goal that it intends to achieve through a collective engagement. In order to achieve it, you need networks. The Gülen movement consists of a number of networks, organized horizontally. In this loose network system, the traditional values and idioms of the community play an important role.

As a movement, it incorporates the network and community, or communal ethos. I would consider it as a movement based on the re-imagining of Islam and consisting of loose networks under the guidance and leadership of Fetullah Gülen.

These networks are not necessarily organized in hierarchical terms. But we see three circles. The first is the core circle around Gülen. The second circle consists of those who give their time and labour in order to achieve the collective goals of the movement. The third circle consists of those who are sympathizers: sometimes they support the movement by writing an article in the media, or they give money, or they support the movement in other ways.

So you have a number of circles, but each circle includes a number of networks. When we examine these networks, there is a sense of solidarity and of the Islamic ethos of brotherhood. This is the glue that joins these networks together.

Religioscope – The most important factor that holds these networks together seems to be Fetullah Gülen himself. Could the movement exist without him?

Hakan Yavuz – You are right that Gülen is in a way the integrating personality of these networks and circles. If Gülen dies, we will see a fragmentation. However, it could be just like the Nur movement: Said Nursi died, but the Nur movement survived and expanded.

After Gülen’s death, I expect a number of new groups to emerge and networks to be revised. I do not think that the movement is going to disappear. It could restructure itself under different names and with different leaders.

Religioscope – You have described the movement as an education-oriented movement. Could we say that an educational project is at the very core of the Gülen movement?

Hakan Yavuz – Gülen believes that the main problem in the world is lack of knowledge, which involves related problems concerning the production and control of knowledge. How do you create knowledge, maintain it and disseminate it? He thinks it can only be done through education. Education is very important if one wants to become a better Muslim.

Education is key. Not religious education: we are talking about secular education, science and the humanities – and of course religion as well. Gülen believes that those three forms of education should enhance and complement each other rather than compete with each other.

Religioscope – What most people know about the Gülen movement has been the creation of a network of schools. Interestingly, the movement did not only create schools in Turkey, but in a number of other countries as well. Does this education-oriented project go along with the movement’s strategic thinking? Is it a way of spreading values that go beyond the confines of the educational project?

Hakan Yavuz – Yes. The Gülen movement believes that we are living in a global world. Muslims are not isolated. Muslim communities are found in many non-Muslim countries. They have to interact and to create a shared understanding, a shared experience and a shared code of ethics.

The movement tries to achieve this through the educational system. By establishing schools in China, in Russia or in Africa, it aspires to educate other people about Islam and to educate Muslims about other cultures as well. It sees education as the only way to create a shared language and shared ethics – and also to create sympathizers around the world, which is the third circle I mentioned earlier.

Religioscope – Sympathizers for the Gülen movement, for Islam, for Turkey?…

Hakan Yavuz – That is correct: sympathizers for Gülen, sympathizers for Islam and sympathizers for Turkey.

The national aspect is very important for Gülen. He believes in something called Turkish Islam, shaped by Sufism, Turkey’s positive experience with the West and Turkey’s transformation. This is an understanding of Islam shaped by the history and contemporary experiences of Turkey.

Religioscope – Does this explain why the Gülen movement is not really active in the Arabic world? Or are there other circumstances that explain this fact?

Hakan Yavuz – You are right, the Gülen movement in not active in the Arab world. One of the key reasons is that some Arab countries do not allow the movement to operate and treat it as an agent of the United States (or even an agent of the CIA, since Gülen lives in the United States). It is also viewed as an agent of globalization. The Arab world is not at all sympathetic to this movement.

Also, Gülen and people around him do not necessarily want to get involved in the Arab world, because they believe that it does not understand Islam properly. In fact, they want to distance themselves from the Arab world. Here you have the nationalist aspect of the movement coming to the fore.

Religioscope – But are there some movements in the Arab world with which the Gülen movement maintains privileged relations?

Hakan Yavuz – As far as I know, no. I do not know any movement that – at the moment – is in interaction or in sympathy with the Gülen movement. In the movement’s newspaper, Zaman, and on its TV station, Samanyolu, I have yet to see an article that praises any Islamic movement in the Arab world as democratic or modern. They are either critical or silent on the subject.

The movement believes that the best Islam is the Islam of Turkey, the Islam that is defended and promoted by Gülen, who is in favour of dialogue and moderation. He has met with Pope John Paul II and several prominent religion scholars. He believes that Islam should not take on an identity of confrontation and conflict, but rather one of co-operation and coexistence.

Religioscope – Beside education, what is Fetullah Gülen’s aim? In the recently published book, you stress that his aim is not to create an Islamic state.

Hakan Yavuz – According to Gülen and the Nur movement, it is anti-Islamic to talk about an Islamic state. But you can create a conscious Muslim. You can create Muslim networks. You can create Muslim ethics and good models of coexistence by utilizing Islam. But when Islam becomes a model for the state, Gülen believes it is not Islam anymore.

His goal is to raise Muslim consciousness and to get involved in modernity, democracy and a free-market economy, so as to get Muslims to enter into those global processes. His goal is also to turn Turkey into a regional power. Turkey means a lot to Fetullah Gülen.

Religioscope – In light of your explanations, it may seem

quite surprising that, in recent years, some hardline secularists in Turkey have become extremely hostile to Fetullah Gülen – even though the movement seeks to avoid confrontation with the state and has sometimes even proved to be subservient to it; for instance, in the early 1980s, when Gülen supported the military coup. How do you explain why the movement has experienced such reactions to its work and teachings? Fetullah Gülen has been living abroad for several years in order to avoid unpleasant experiences.

Hakan Yavuz – In my book Islamic Political Identity in Turkey (Oxford University Press, 2003), I have attempted to explain that, when Turkey started to go through a process of neo-liberal economic reform in the early 1980s, it created a space for new opportunities. This allowed variousidentities to become more public, particularly communal processes. For instance, Kurdish and Alevi identities became more assertive. The Kemalist military state wanted to exploit the Gülen form of political Islam and they did, using it against Erbakan (the ex-Prime Minister and leader of political Islam in Turkey for many years).

After the military and their allies got rid of Erbakan, they turned against Gülen. Gülen represents a major threat for these people, because they want to see a backward, radical Islam, in order to justify repression – whereas with Gülen, you do not get that. This angers them even more!

Also, Gülen tries to educate the periphery by teaching them foreign languages and providing scholarships for study in foreign countries. This angers the establishment as well, because they want to control the country and not to share the resources with the rest of the population. There is also a conflict over resources. Gülen was on the side of the poor, while the establishment did not want to see his movement opening up educational opportunities for the marginal sectors of Turkish society. This frustrated militant secularists in Turkey.

Religioscope – What do the Gülen movement and the Nur movement in general represent in contemporary Turkey in terms of influence, intellectual impact, numbers, and so on?

Hakan Yavuz – The movement is very active, and is responsible for newspapers, financial institutions, the best hospitals and private high schools in Turkey, and so forth. It is part of every aspect of Turkish life. It tries to set a good example and to improve standards. I think it is well integrated into Turkish society.

The movement wants to provide a good image of Islam, not so much through indoctrination, but to teach Islam through its members setting a good example by becoming good doctors, good mathematicians, good politicians, good cooks, and so forth. Such people want to teach Islam by doing their duty properly.

In a way, they represent a new model of Islam in Turkey, at peace with democracy and modernity. This also reflects the Anatolian understanding of Islam, i.e. the Sufi conception of morality is at the centre of the movement.

It also stresses the “greater jihad” (jihad al akbar), i.e. the control of one’s nafs (lower desires).

I think it has played a very positive role in developing closer ties with European countries.

Religioscope – Could we describe such a movement as an expression of post-Sufi trends?

Hakan Yavuz – Yes, one could see it as post-Sufism, or as a new Sufism – a religion structuring social interactions by reutilizing and reinterpreting religious values without imposing religion on society. It has to do with action informed by religion.

Religioscope – People involved in the Gülen movement are not involved in Sufi brotherhoods, are they?

Hakan Yavuz – No, they are not. Members of the Nur movement are not members of any Sufi group, because they believe that the age of Sufi tarikat [Sufi brotherhood] is past. Yet they believe that the ideas of morality, religion and God could be remodelled and utilized in the modern age.

Religioscope – And what is the interaction between the followers of Fetullah Gülen and the current leading party in Turkey, the Justice and Development Party (AKP)? Do they tend to belong to this party or do they vote primarily for parties without a Muslim background.

Hakan Yavuz – In previous elections, members of the movement voted for Bülent Ecevit (Democratic Left). In recent elections, I think their votes were divided between the AKP and Ecevit. Members of the movement do not necessarily vote for Muslim parties. They actually try to stay away from any party that describes itself as “Islamic” or “Muslim”. But they have very good ties and relations with the AKP government.

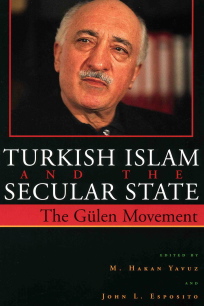

M. Hakan Yavuz and John L. Esposito (eds.), Turkish Islam and the Secular State: The Gülen Movement, Syracuse (New York): Syracuse University Press, 2003, XXXIV+280 pp.

The interview was conducted by Jean-François Mayer.